Jaime González serves as the Houston Healthy Cities Director for The Nature Conservancy, which helped to develop Greener Gulfton. He works with decision-makers and scientists to bring nature-based solutions to communities throughout the Houston area to be climate-ready, healthier and more biodiverse. He outlined several challenges that need addressing to make Greener Gulfton a reality.

“Gulfton has several different aspects of nature inequity,” González said. “Although residents are genuinely concerned about the increasing burden of climate change, many of them come from rural backgrounds. They want their children to have the wonder and awe of nature — the soul-affirming part of nature. Being in a community that doesn't have as much nature means there isn’t room for those meaningful perspectives.”

González pointed to Burnett Bayland Park, on Gulfton’s east side, as an example of park inequity. People who live in the western portion of the neighborhood are more than a 10-minute walk away, with no other green space or park options.

“The park has not been redeveloped in some time,” he said. “It is in need of a master planning process and a reinvigoration. It's a heavily used park, but it can be transformed into something that is more useful. Not only for recreational value, but in terms of resiliency, in terms of wanting to absorb more water and biodiversity.”

Other components of Greener Gulfton seek to implement an urban forestry strategy and sustainable stormwater solutions, increase gardens and natural habitats at schools and the creation of nature-rich civic spaces. Since these plans will not happen overnight, a pilot project, “La Placita,” would bring small, semi-temporary plazas where residents can enjoy the outdoors without visiting Burnett Bayland Park.

A pressing need remains for cooler corridors for the many residents who use public transit. Despite Gulfton’s need for more trees, it does not have many places to plant them. It is also one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in Houston for pedestrians. Potential solutions could be incorporating more green space into bus stops, and using alternative methods for tree canopy cover.

“Gulfton is a fairly dense neighborhood, which means that the pedestrian corridors in the neighborhood won't allow space for trees,” González said. “We're going to have to find alternate shading structures. It could be trellises or mechanical shade structures. If you don’t have a developed tree canopy cover, not only is it bad for heat, but it’s bad for the stormwater collection system.

“Trees intercept and soak up water, and can trap a lot of particulate matter while preventing it from ending up in the lungs of community residents. There are a cascade of impacts when there is poorly-developed nature, but there's a lot of innovation that could happen.”

González said that Greener Gulfton’s goals are in various stages of activation.

“Some of these things are really embryonic, and some have movement,” he said. “There’s already funding for a master plan for Burnett Bayland Park. There's funding for some tree plantings. It’s one initiative with many parts and different timelines.”

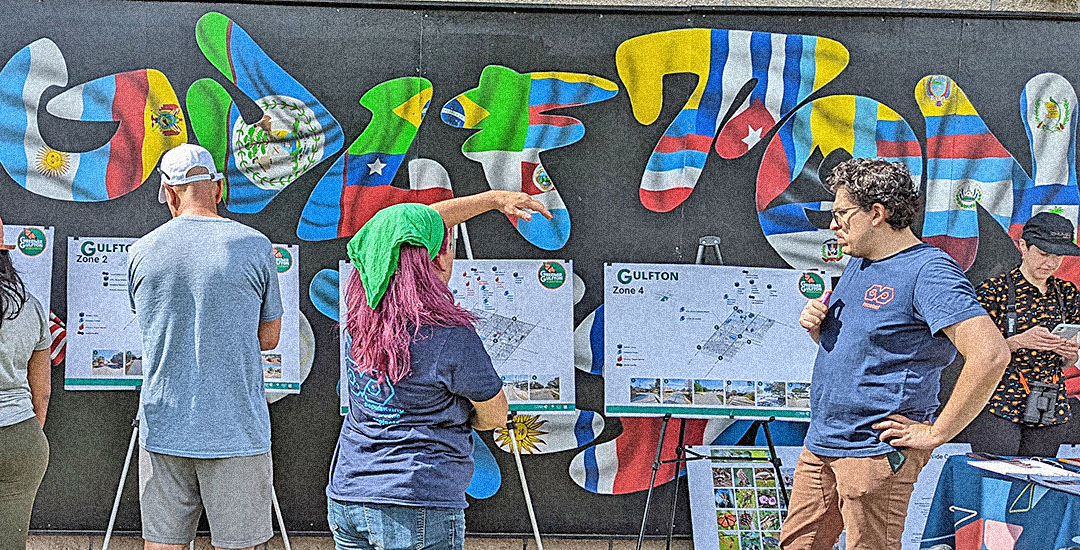

Greener Gulfton is a collaboration between the Gulfton Super Neighborhood Council, Connect Communities, Madres del Parque, Harris County Public Health, Houston Health Department, The Nature Conservancy and community members, including the Greener Gulfton Ambassadors. The plan was developed in partnership with landscape architecture firm Asakura Robinson, community engagement firm Tecolotl, and public art nonprofit UpArt Studio.

Disinvestment in Gulfton has led to negative cultural, economic, health and sociological impacts. But Greener Gulfton’s organizers are optimistic they could receive federal, state and local funding to synchronize with actions the city and Harris County have already expressed an interest in.

Sandra Rodríguez, president of the Gulfton Super Neighborhood Council, has lived there for almost four decades. She said Greener Gulfton materialized at an ideal time, alongside separate projects involving beautification, street redesigns and an emphasis on improving walkability and addressing the dangers presented by street traffic.

“What many of us in the neighborhood are trying to do is change the negative image some people have about Gulfton,” Rodríguez said. “This project will improve public safety, improve people's well-being, both physically and emotionally. We want to really bring to life the beauty of our neighborhood and the beauty that the immigrant community brings to this neighborhood, city and country.”

The median household income in Gulfton is $31,000. In 2017, Gulfton was designated as one of several Complete Communities by Mayor Sylvester Turner. The citywide initiative seeks to improve underserved neighborhoods with more access to affordable housing, education, jobs and other services. One of Greener Gulfton’s priorities is to pour economic and vocational benefits back into the community.

“Creating a Greener Gulfton will bring more economic development for our neighborhood and more investments for our community to thrive,” Rodríguez said.