North and South boulevards in Boulevard Oaks just might be the most beautiful streets in Houston, particularly the segments between West Boulevard and Parkway Drive in the Broadacres subdivision.

They’re certainly the most photographed.

Over the years, countless brides-to-be, newly engaged couples, proud parents cradling newborns and quinceañeras have posed beneath the grand canopy formed by the large, venerable live oaks lining either side of the wide esplanades that bisect both boulevards.

They’re such popular spots for photo shoots, in fact, that a few years ago the Broadacres Homeowners Association attempted to make the esplanades off-limits to the public. In the end, the city, which owns the streets and the brick-paved sidewalks that run down the center of the esplanades, stepped in and declared the homeowners couldn’t restrict use of the public space.

The shade provided by the live oaks and other mature trees in Broadacres, which was developed in the 1920s by none other than James A. Baker, the attorney for William Marsh Rice and the man who solved his murder, helps keep the average temperature at a relatively cool 82 degrees. The canopy covers 42% of the area’s surface.

Trees shade 38% of West University Place, where the median household income is $190,000. The canopy covers 44% of census tract 4124, at the heart of West U, helping to lower the average temperature to 83 degrees.

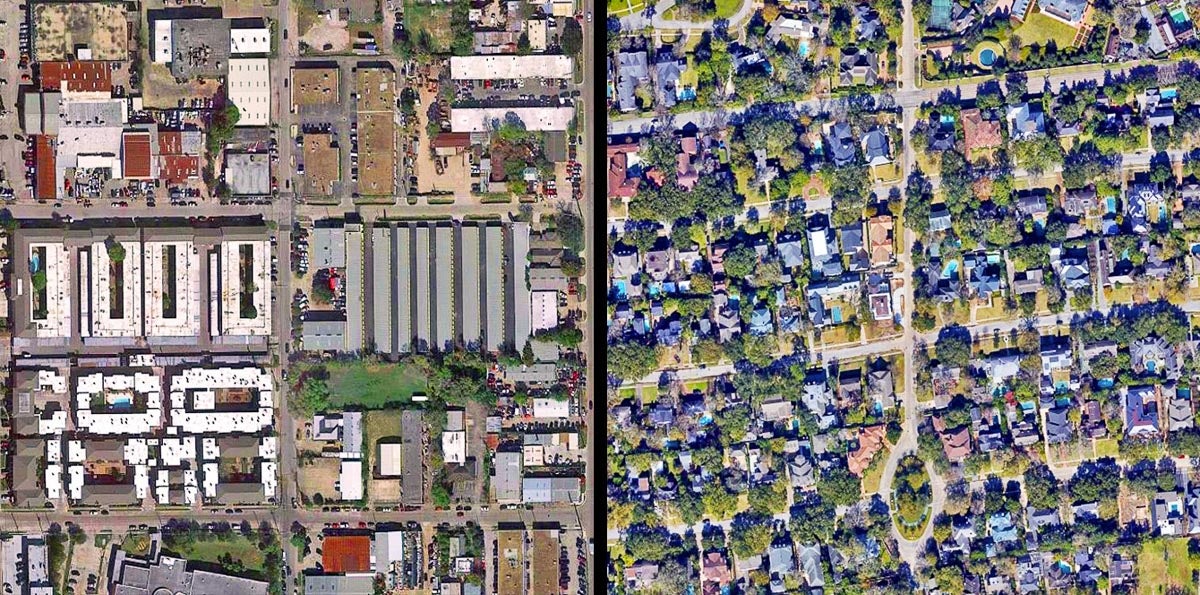

In contrast, just five miles to the west in Gulfton, where only 6% of the area around Benavidez Elementary School and the San Lucas Apartments is shaded, the average temperature is 90. There, the median household income is $31,000 and close to two-thirds of residents live below the poverty line. The Las Velas and Fairmont apartment complexes are located between Bellaire Boulevard and Bissonnet Street, in an area of Gulfton where just 4% of the surface is shaded by trees and the average surface temperature is 91. The median household income in the neighborhood is $39,000 a year and the poverty rate is 82%.

As former Kinder Institute research fellow Chris Servidio pointed out in a 2019 Urban Edge piece: Shade, regardless of the source, is especially important to those who navigate Houston on foot or by public transit. In Gulfton (left), where roughly 8% of workers rely on transit and 13% of households don’t have access to a car, shade becomes an even more important factor in the daily lives of residents. Arguably, it’s more important than in more affluent and shadier neighborhoods like River Oaks (48–50% tree cover), where less than 2% of residents take public transportation to work, while enjoying average temperatures of 80–81 — 10 degrees cooler than in Gulfton.

Google Earth images

All of this data on shade comes from the Tree Equity Score, which examines and maps to what extent tree canopy cover is equitable in American cities. As the above comparisons of Houston neighborhoods indicate, it’s the socioeconomically disadvantaged areas and communities of color that are suffering the most from urban tree inequality in the U.S.

The tree equity project is an initiative of American Forests and is based on an analysis of income, employment, age, ethnicity, health and surface temperature, combined with tree canopy data for 486 metro areas (home to over 80% of the U.S. population). The nonprofit’s urban forestry study shows that, on average, in neighborhoods where the majority of residents live in poverty, there’s 25% less tree canopy than those where 50% or less of residents are in poverty. In the most extreme cases, the report shows, wealthy neighborhoods have 65% more shade than the poorest communities. And in neighborhoods where the majority of residents are people of color, there is 33% less tree canopy on average compared to majority-white neighborhoods. (Neighborhoods are defined in the analysis as urbanized Census Block Group with a population greater than zero.)

In Houston, there’s a discrepancy of about 14% between tree canopy cover in the wealthiest and the most impoverished neighborhoods, says Ian Leahy, vice president of urban forestry at American Forests. And it has a 16% difference between communities with the highest share of white residents compared to those with the highest share of residents who are people of color.

Trees cover 58% of Hunters Creek Village, and the average temperature is 82. The small city is located in Memorial Villages, where the population is 78% white and more than 75% of households make more than $100,000 a year, but only 0.31% of workers rely on public transportation and less than 1.5% of households are without a car.

Google Earth image

It isn’t news that poorer neighborhoods and communities of color have less tree cover and higher average temperatures. But what is new about the Tree Equity Score is the accessible format of the data and an interactive map of cities and metros that shows where the shade inequalities are greatest, as well as how many tree-plantings it would take to get closer to tree equity.

“It’s important to think of the urban forest, particularly in Houston, as infrastructure, and making sure that infrastructure is expanding out and in places where it’s going to have the most impact,” Leahy explains. “Those are places where people might not be able to afford air conditioning, where they’re outside more, and where there are more elderly residents.”

This isn’t to say that wealthy neighborhoods don’t deserve their beautiful, years-old oaks and shady sidewalks, rather it’s to underscore the need for more trees in many less wealthy areas of Houston.

The report on the study shows that to achieve tree equity in the nation’s urban areas, 31.4 million trees need to be planted each year in metro areas across the U.S. That’s enough trees to cover a little more than 43% of urbanized areas. Currently, trees shade only about 33%. Planting that many trees each year isn’t cheap — a cost of almost $9 billion — but in the long term, the projected pay-off would make it worth the investment.

Annually, the trees would mitigate 56,613 tons of particle pollution while removing 9.3 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere — that’s equal to taking 92 million cars off the road, according to the report. Doing so could also lead to the creation of 3.8 million jobs, and help curb some 478 million cubic meters of stormwater runoff every year, according to the report.

Only about 18% of Houston is currently covered by tree canopy — some 33 million trees mostly located on private property. To achieve Tree Equity — a score of 100 in all neighborhoods — approximately 2.4 million trees need to be planted.

This would increase the size of the city’s tree canopy to 23% and could support more than 17,000 jobs. It would also help eliminate 2.2 million cubic meters of stormwater runoff — about 581 million gallons. More than 13.5 million cubic meters of rainfall would be intercepted by the additional canopy, keeping it from running straight into the stormwater system and overwhelming it.

Trees cover as little as 3% of some Sharpstown neighborhoods, and the average temperature is 91. Almost 32% of Sharpstown residents live in poverty and 64% of households make less than $45,000 a year, while close to 6% use transit and 13.8% of households don’t have a car.

Google Earth image

Overall, the city gets a tree equity score of 94, which is better than other large cities. Los Angeles, for example, gets a score of 80 and comes up some 5.2 million trees short of equity. Regionally, Houston’s score is higher than most of the smaller, surrounding cities and suburbs, including Bellaire (88), Pearland (87), Tomball (87), Conroe (81), Rosenberg (79), Humble (63) and Webster (61).

Dallas’ score is 93, but only needs about 468,000 additional trees; while Fort Worth (89) needs almost twice as many: 895,000. El Paso scored a 65 and needs more than 1 million trees to reach full equity.

Houston, Fort Worth and El Paso, along with Chicago, Phoenix, L.A. and Portland, Oregon, are among the 20 biggest cities with the largest gaps in tree canopy to fill to reach tree equity, but they also have the most to gain in terms of health, economic and climate benefits.

In cities across the U.S., healthy trees prevent roughly 1,200 heat-related deaths and many more heat-related illnesses each year. Heat kills more people than any other type of extreme weather. And scientists predict the largest U.S. cities will see those deaths increase by 70% to more than 100% by 2050.

At 66%, this area of Briar Forest (block group 1 of census tract 4508.01), just outside of Beltway 8, has the largest percentage of tree canopy cover in Houston, According to the Tree Equity Score. The average temperature is 83 degrees. People of color make up 27% of residents and 9% of the population lives in poverty. Just a mile south, where only 10% of block group 4 of census tract 4508.02 is shaded, the average temperature is 91. The population of the neighborhood is overwhelmingly composed of people of color — 85% — and 59% live in poverty.

Google Earth image

A new analysis from the independent research group Climate Central gauged the intensity of urban heat islands across 159 cities by estimating the difference between the average temperature in city centers compared to less developed surrounding areas using measurements of the types of land cover (from green space to concrete and asphalt, as well the height of buildings and population density) in each city. Cities were then scored based on heat island intensity. Houston ranked fourth for the largest spikes in urban heat, scoring high because of the large percentage of impermeable surfaces that constitute the city’s topography.

Trees are powerful weapons in the fight against the urban heat island effect, which can raise temperatures as much as seven degrees during the day and 22 degrees at night. And neighborhoods typically are divided along race and class lines in terms of which experience the highest temperatures.

Urbanization and the need to protect existing trees

More than 140 million acres of the nation’s forests are located in cities and towns. Urban forests are responsible for almost one-fifth of the country’s captured and stored carbon emissions, according to the American Forests report. However, the U.S. is on a path in the wrong direction. For every two trees being planted or naturally regenerating, one is lost. The causes range from extreme weather events, insects and diseases to removal for new construction and poor planting practices. At this rate, more than 8% of the nation’s urban tree cover is expected to be lost by 2060.

In the next 40 years, the population of Harris County is expected to grow by 2.3 million people, second only to Maricopa County in Arizona (2.8 million). As urban land increases, urban forests will also grow; however, tree cover is expected to decline as more green space is replaced by buildings, concrete, asphalt and other impervious surfaces. This also means a decrease in the amount of surfaces that absorb rainfall and help cool the surface. In the next 10 years, the tree cover in Harris County is projected to decrease by up to 4.9%, and from 5–9.9% by 2060.

However, if Harris County is able to preserve its current share of tree canopy and increase it by 10% over the next 40 years, it could save as much as $31 million in annual energy costs, cut carbon emissions by almost 45,000 tons, store up to 3.3 million more tons of carbon and save another $10.4 million in other offset emissions costs. The annual cost savings generated by the offset in emissions in the county would be $8 million or $10.4 million with canopy conservation or enhancement.

Concrete and asphalt, which retain heat and raise temperatures, make up a lot of the land cover in Westwood and other areas of Houston.

Google Earth image

Efforts to plant more trees in Houston

Without proactive efforts to plant and protect new trees every year, as well as protect existing trees, experts say, the benefits of urban forests won’t be able to keep pace with climate change and the rapid urbanization of the U.S.

Trees for Houston has its own “tree report card” for the city based on existing tree canopy, income, historic and cultural makeup of neighborhoods, says Barry Ward, executive director of the nonprofit.

Trees for Houston worked with the Environmental Defense Fund, Houston air Alliance and the city of Houston to ensure the report card reflects the areas that are most in need of more trees and how many, Ward says. “And what we found is, although these tools and these metrics are very helpful, most of the time, you don’t really need them,” he adds. “You know exactly where to plant.”

“I’m not saying that these report cards (such as the Tree Equity Score) are a bad thing,” Ward says. “They’re great at drawing attention to problems. But the real challenge is not with knowing where to plant; the real challenge is getting trees into those areas.”

Through its Trees for Neighborhoods program, the group gives trees to communities in need for planting. The nonprofit put around 26,000 trees in the ground last year, Ward says, and the goal in the next decade is to increase that to 100,000 trees a year.

There are multiple tree-planting initiatives currently at play in Houston, which will be covered in more depth in an upcoming Urban Edge post. One ambitious example comes from Houston’s Climate Action Plan, in which the city set a goal of planting 4.6 million new trees by the end of the decade. More than 700,000 were planted from 2019–2020, and another 377,000 plantings are projected this year.

There is an 18% tree canopy gap in this area of Northside / Northline.

Google Earth image

But where will all of those trees be planted? Answering that question gets trickier in the most densely populated areas of the city, such as Gulfton, Westwood and Mid-West, where multi-family units comprise most of the housing, and a significant share of residents live below the poverty line. Many neighborhoods in these communities fall far short of the tree canopy goals set by American Forests. (These goals are the percentage of tree canopy recommended for a particular area based on “natural biome and population density.”) With block after block of large portions of these neighborhoods covered by sprawling, 1970s-era apartment complexes and their vast parking lots, there’s little room for trees. When they were built, green space was not a priority for the developers or the city planners who designed the streets.

“The traffic engineers two or three generations ago believed that any space not devoted to getting a car to go faster was wasted space,” Ward says.

One of the challenges of urban densification in places where space is used more efficiently, whether it be in Hong Kong, San Francisco or Gulfton, is where to plant the trees. In Houston neighborhoods, Ward says, “the immediate solution is to put them in the esplanades in the middle of the street, and anywhere you can in the strip of grass between the sidewalk and the street, if there’s enough room. That’s the first thing you do.”

Through what is called its Linear Forests Initiative, the city is expected to create a plan to reforest esplanades across Houston. And according to the Climate Action Plan, tree-planting through the program will be prioritized in underserved communities.

Maybe it’s possible that one day there will be canopy-covered esplanades as beautiful as those in Broadacres throughout the city. If so, it’ll mean increased access to shade, as well as backdrops for photo shoots, for more Houstonians.