Houston is amid a transportation paradigm shift. Transportation in Houston has typically prioritized one mode: cars. Like many cities, widening roadways to solve congestion has been common practice even though mounting evidence shows this only adds more drivers and more traffic. Wide roads with multiple lanes reinforce sprawling urban growth and are also linked to higher rates of traffic-related deaths.

The impacts of these findings are slowly filtering into public opinion. Over the last four decades, the Kinder Houston Area Survey has revealed that traffic congestion was one of Houston’s biggest problems. In 2003, when the survey added a question about long-term solutions to traffic problems, 63% of respondents indicated building bigger and better roads and highways. In 2015, this dropped to 26%. Houstonians taking the survey also expressed the desire for more walkable neighborhoods and complete streets to accommodate transit and biking. While traffic congestion continues to be a concern, the recent conversation around solutions is shifting to improve streets for other modes of transportation rather than solely build wider roadways.

In cities around the world, Vision Zero is catalyzing a shift in traffic safety. A traditional approach expects people to perform perfectly and relies on behavioral changes. Vision Zero uses a “Safe Systems” approach, where the responsibility is on the transportation system—and those who design and build it—to anticipate human error and accommodate injury tolerance. Advancing the Safe Systems approach requires a culture that emphasizes safety over competing goals and demands. This means dismantling the status quo, making Vision Zero a long-term commitment. For example, Swedish parliament adopted Vision Zero policy in 1997 and, after halving the number of traffic fatalities by 2010, renewed its commitment in 2016. Evidence shows a slow, deliberate process is necessary in shifting transportation paradigms and reducing traffic deaths.

Vision Zero is not Houston’s first plan for improving street safety, but it is the first to demonstrate a commitment to saving lives over prioritizing cars. This commitment is formalized with Houston’s Vision Zero Action Plan, which sets clearly defined goals to end traffic deaths and serious injuries by 2030 and improve street safety for all. The plan, released in 2020, attempts to shift the city toward a strategic approach grounded in the mindset that no loss of life by traffic crash is acceptable. It is bolstered by resiliency and climate action plans which identify multimodal transportation as a key element to strengthening communities.

Houston’s future as a resilient city relies on multipurpose infrastructure that keeps people safe. This is a change from the traditional belief that streets are for cars toward a Vision Zero framework that streets are for people.

Challenges for Houston

The scale of Houston, a Metropolitan Statistical Area larger than New Jersey, presents challenges to a paradigm shift including sprawling development patterns, engagement with people across varying places and cultures, and a lack of dedicated funding for Vision Zero.

In Houston, low housing costs have been partially enabled by an expansive network of freeways intended to facilitate short commutes from suburban and rural areas. Unfortunately, these development patterns have failed to prevent freeway congestion or increase the supply of affordable housing—nor has it resulted in safe streets.

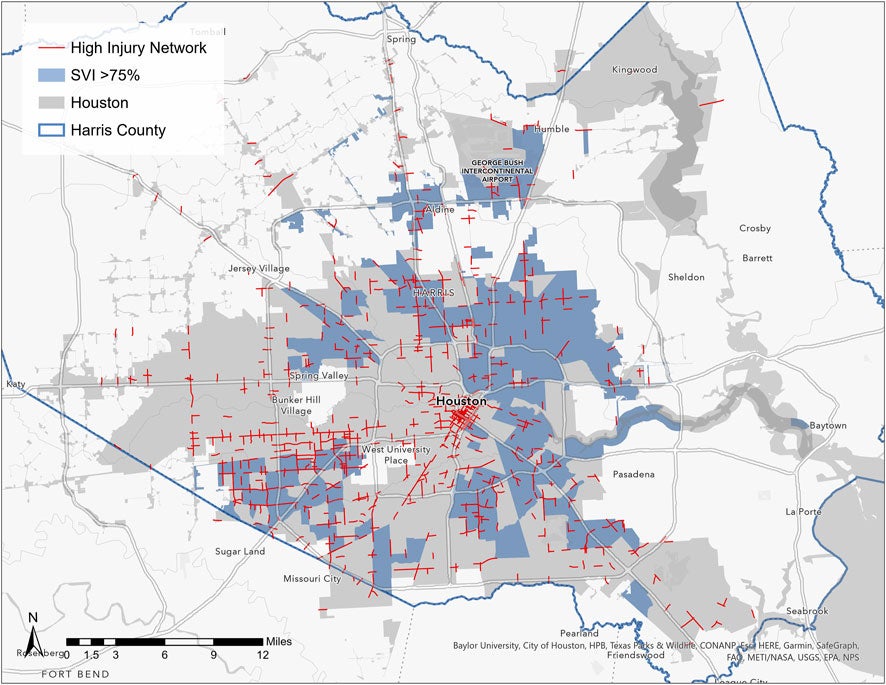

Developed as part of the commitment to Vision Zero, Houston’s High Injury Network contains the 6% of Houston streets that account for 60% of crashes resulting in serious injury or death. Dedicated, safe infrastructure for transit riders, cyclists, and pedestrians remains rare.

Of the 9,200 miles of Houston streets that are not limited access highways, there are 5,600 miles of sidewalks. If every street had a sidewalk on both sides, there would be 18,400 miles of sidewalks. When present, sidewalks are often narrow, poorly maintained, or impassable for those with mobility impairments. The Houston Bike Plan has increased bike facility construction, and as of the January 2022, there are 436 miles of high-comfort bikeways. However, only 29 of those miles are high-comfort, on-street facilities. The remaining 407 miles of high-comfort bikeways are largely off-street trails through natural areas. The transit system in Houston is well used and provides access to much of the city. However, most transit vehicles operate in mixed traffic, which slows service.

Houston is considered the most diverse city in the nation. In Harris County, 45% of households speak a language other than English at home, according to Census Bureau estimates. Its 88 neighborhoods require unique approaches to outreach because of varying language, culture and experiences. Residents in socially vulnerable neighborhoods have memories and recent experiences of top-down implementation of projects instead of community-driven planning. Unfortunately, a disproportionate number of severe crashes occur in these neighborhoods, and because of historic underinvestment in roadways, these areas have over 52% of the city’s High Injury Network streets.

Meeting the community where they are is integral to connecting their vision for safe streets to proven safety countermeasures. During recent Vision Zero engagement, vehicular speeding was the top traffic safety concern expressed by community members. However, measures to slow speeds are judged by some residents based on the level of perceived inconvenience for drivers rather than the effect of slow speeds which save lives, prevent injuries, and increase accessibility. Bridging the outreach and engagement gap between reported concerns and proven safety countermeasures remains a challenge.

While the commitment to Vision Zero has been made, there is no direct funding stream to support it. After six major flooding events with federal disaster declarations in five years, funding in the Build Houston Forward program is geared toward paving and drainage, though there are opportunities to include street safety improvements in road projects. Other current mechanisms include Capital Improvement Program funding, which has directed $5.5 million over five years to improve safety for cyclists.

The dangerous roadway design problem

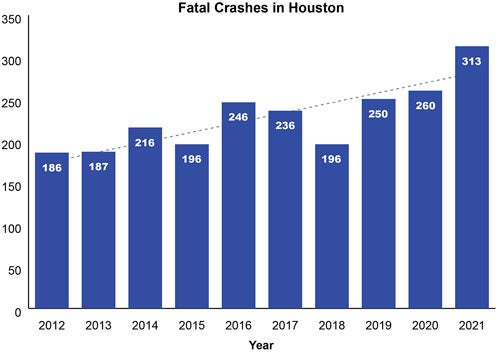

From 2012 to 2021, traffic fatalities rose annually by an average of 6%. Vulnerable road users are disproportionately impacted by traffic crashes. Pedestrians represent 2% of commute-to-work patterns yet over 30% of traffic deaths. City streets, where different modes of travel frequently mix, account for 53% of traffic deaths and serious injuries in Houston over the last decade, which suggests streets have not been designed to protect all road users. Dangerous roadway design leads to unsafe conditions for everyone.

Multilane roadways are dangerous because they induce heavy, high-speed use of roadways and result in high rates of traffic deaths and serious injuries. In Houston, these roadways overtake the city. The pavement area of Houston roads could bury Paris and Barcelona combined. Priority streets in the High Injury Network are an average 80 feet wide with six lanes from curb to curb. Posted speed limits are 35 mph but the average speed traveled (85th percentile) is 43 mph.

Much of Houston’s major streets have been designed to move vehicles quickly. They have been built to accommodate assumed future car traffic without acknowledging induced demand, multimodal access, or transportation demand management, and have been sized for the few peak hours of the day when there are the most vehicles on the road. While this traditional methodology is not unique to Houston, the outcomes are more widespread. Major streets, streets with many lanes and high traffic volumes, including all non-limited access highways, make up only 16% of roadway miles in Houston yet 77% of the High Injury Network. Wide streets with multiple lanes account for an alarming number of traffic deaths and serious injuries and contribute to the car culture Houston is attempting to shift.

Adding more vehicle lanes invites more drivers. Census data shows that 86% of employed Houstonians report using a car to travel to and from work. In 2019, Harris County averaged 25 daily vehicle miles traveled miles per capita. By comparison, Los Angeles County had a per capita of 21 miles. Only 6% of people report walking, biking, or taking transit to work in Houston; in Los Angeles, it is 12%. The distribution of those using alternative modes of transportation varies. For example, in Houston census tracts, the percentage of people taking public transit to work ranges from 0% to as much as 28%. But anyone walking, biking or using a mobility aid in Houston knows they are in the minority through their experience with the infrastructure available and the roadway users they encounter.

People on the streets are up against drivers who speed, swerve, run red lights, and infamously “roll coal.” While not specific to car culture, the “everything is bigger in Texas” mantra can explain why some Houston drivers feel emboldened to take to the streets in such dangerous fashion. It aligns with a belief that bigger is better – bigger trucks, bigger roads, bigger gas stations, and bigger convictions about transportation options. There is a lot of space for cars and very little for the people outside of them. Only 56 miles of Houston roadways include safe, dedicated space for transit or biking. Houston built out so wide and fast that it missed a key element of strong communities: a Texas-sized commitment to streets for people.

People in Houston are suffering the deadly consequences of overbuilt roadways. In 2021, five people were seriously injured and someone lost their life nearly every day in vehicle crashes. Speeding is the main contributing factor in 27% of fatal crashes. Drivers use roadways as designed, and wide roadways with multiple lanes enable higher speeds, which result in more severe crashes. Reprioritizing streets for safety of all road users is the start to shifting the culture and creating safe, accessible ways for people to traverse the many miles and neighborhoods in Houston.

Evidence of a changing paradigm

Expectations are changing within the City of Houston because new leadership is prioritizing Vision Zero. Beyond those who developed the action plan, staff across City departments are incorporating Vision Zero policy into their work. The city’s first Chief Resilience Officer was hired in February 2019. The Resilient Houston strategy was released in 2020, establishing a goal to implement Vision Zero. In March 2020, the city hired its first Chief Transportation Planner, and the Vision Zero Action Plan was released in December 2020. Within the plan, Mayor Turner states “in Houston, we can prioritize safety over convenience.” This call from the top is how cultures can start to change in places like Houston with a strong mayor-council form of government. In February 2021, Houston Public Works appointed a new director of Transportation and Drainage Operations with previous experience leading Vision Zero action plans. Key roles are filled by Vision Zero champions who are providing critical support and commitment to shifting Houston’s traffic safety culture.

The implementation of major multimodal plans and policy in the last two years is another example of Houston’s changing priorities. The Vision Zero Action Plan contains 50 goals, and progress has been made on many, including all 13 priority actions. The High Injury Network is now a standard part of the design concept review for right-of-way modifications, prompting further investigation of opportunities to improve street safety with every project, big or small. The High Injury Network is used and referenced across City departments, by interagency partners, and by the private sector as a key piece of evidence in justifying safety improvements.

The city is also working to change the process for improving streets from request-based to data-based. Streets are prioritized for safety improvements based on crash patterns and demographic data. City staff push for that prioritization to dictate how the limited street safety funding is spent. City Council approved the Walkable Places and Transit Oriented Development ordinance in August 2020. These ordinances are geographically limited, but the intent is to expand the regions in the future. In 2022, the city will update its Infrastructure Design Manual with standards and requirements that will improve the safety for those using City of Houston streets. These updates will put less focus on vehicular throughput (otherwise known as level of service) and will prioritize enhanced safety treatments and higher standards for bicycle facilities, the pedestrian realm and transit.

The shift is occurring at other levels of government as well. The Houston-Galveston Area Council, which directs how federal transportation dollars are spent in the region, is the first Texas metropolitan planning organization to commit to Vision Zero. Harris County has included a Vision Zero commitment in its 2040 Harris County Transportation Plan. In November 2019, Houston METRO succeeded in passing a referendum to fund a $3.4 billion program to improve and expand transit in the region. The Texas Department of Transportation has also adopted the goal to end traffic deaths by 2050.

Lasting change

A lasting traffic safety culture shift cannot come from government offices alone. We need the public to:

• Earnestly consider what the purpose of a street is. Streets have many uses. They are active and passive. They move and hold water. They accommodate both a quick jog and a long conversation. They get you where you need to go and bring you deliveries. They allow you to rest and take you on new adventures. The use of a street changes every moment and it must be safe for all its uses.

• Shift its mindset. A safe, resilient Houston cannot be achieved by continuing to build for cars alone. Wide, multilane roads have not improved our safety, and they do not reduce congestion long term. Walking, biking, and taking transit are solutions to traffic violence and traffic congestion, and it is possible to design our streets for these solutions and accommodate driving.

• See Houston streets with new eyes. Wide, overbuilt roadways are an untapped asset. We need you to demand that excess street space be reimagined to allow for uses that are safe and enjoyable for everyone. We need community members who support safe streets for all road users to be just as outspoken as residents who fear changing priorities.

We believe streets are places for people of all ages and abilities to travel, play, shop, build community, and live. Loss of life due to traffic violence is unacceptable. Organizations like LINK Houston, Bike Houston, and Air Alliance Houston are pushing the city to end traffic deaths and improve street safety for everyone so that transportation contributes to a healthier and more resilient Houston. To achieve this, the city needs community accountability and to be supported with appropriate funding. Community members deserve to see data-based evidence of improvements and experience safe streets through the Vision Zero strategy. The city will continue to change its traffic safety culture to achieve Vision Zero by designing streets for people, not just for cars.

The community must believe this is possible—that is how paradigms shift for good.

Lauren Grove and Virginia Lynn are analysts for Houston Public Works. This article is adapted from a version that appeared in the journal Frontiers in Future Transportation.

The views, information or opinions expressed in Urban Edge posts are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research.