Just before he left office at the end of 2020, retiring Harris County Precinct 3 Commissioner Steve Radack stoked the ire of cyclists who ride the paved trails at Terry Hershey Park in West Houston. At issue was the decision to set a 10 mph speed limit at all times on trails in Precinct 3 parks. Since 2005, cyclists were required to ride 10 mph or less only when passing runners, walkers and other trail users.

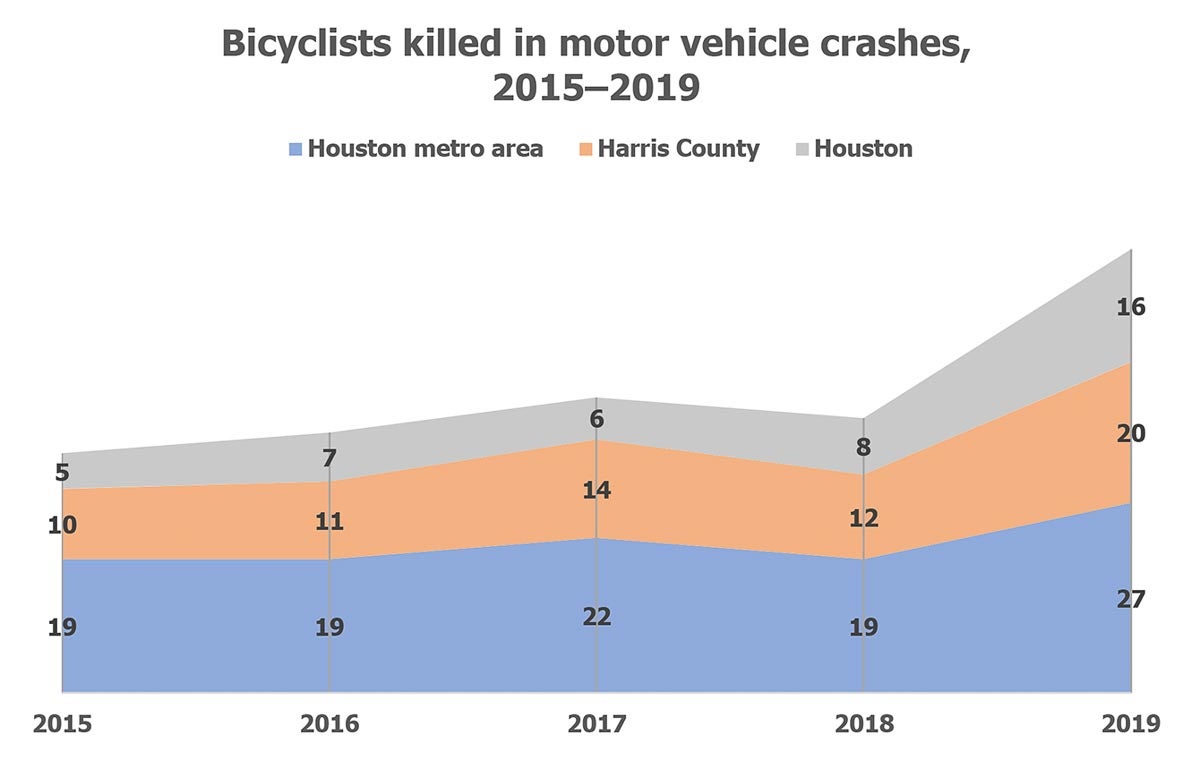

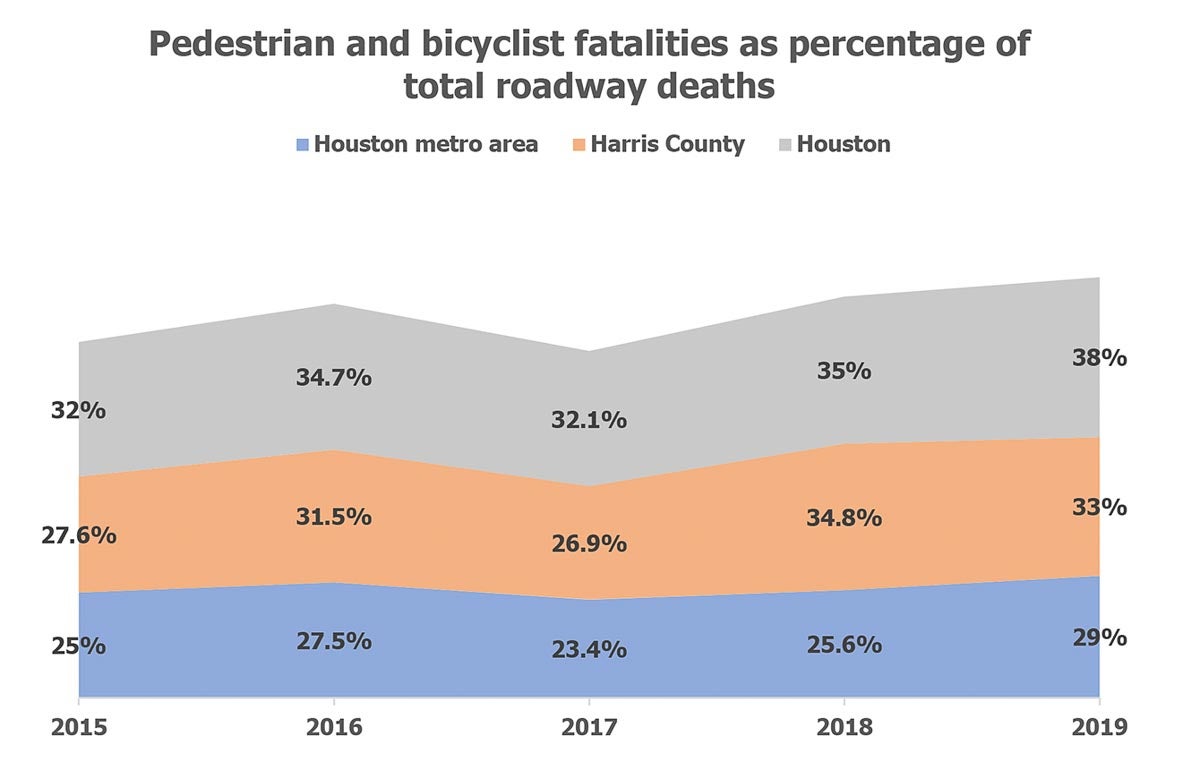

Those opposed to the change couldn’t overlook the irony of dramatically capping speeds on trails used by many who don’t feel safe biking on the streets of Houston. And it’s hard to fault them considering pedestrians and bicyclists accounted for 33% of all roadway deaths in Harris County in 2019. That’s up from 29.6% in 2018, according to data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

Urban Reads presents Angie Schmitt on the undeterred reign of the automobile in cities

On Feb. 17, the Kinder Institute will host journalist and sustainable transportation expert Angie Schmitt as she discusses her new book, “Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America,” as part of the institute’s Urban Reads series. In the book, Schmitt examines the dramatic rise in pedestrian deaths in the U.S. during the past decade, as well as programs and movements that are beginning to respond to the epidemic.

This webinar is free, but registration is required.

Meanwhile, drivers aggressively fly down freeways every day, weaving through traffic with zero concern for the lives of themselves and those around them. The problem of excessively high rates of speed and impatience on area roadways is nothing new, nor is the lack of any substantial enforcement of speed limits. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the issue has blossomed into a full-blown epidemic, one accompanied by a sharp rise in road rage shootings — at least six of which have ended in deaths.

Freeway terror aside, there’s the bad behavior many drivers display on dense residential streets, which have experienced greater levels of activity and what professionals call conflict density during the pandemic as more people and families take walks and bike rides. (We’ve all seen the “Drive like your kids live here” yard signs these drivers inspired long before COVID-19.) And speed is deadly. It was a factor in 25% of all fatal crashes in 2018, the NHTSA has reported.

On Houston streets, the default speed limit is 30 mph, a speed at which the average person has about a one in four chance of surviving if hit, according to the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. On average, there’s a 10% risk of death if a person is hit by a vehicle going 23 mph. As speed is increased, that risk quickly jumps, to 25% at 32 mph, 50% at 42 mph and 75% at 50 mph. And anyone who’s lived in Houston for very long knows it’s not uncommon to see someone driving 40 mph or more on minor streets in this city.

Reducing speed limits has limited returns

Research shows that big safety gains can be won with even small reductions in speed. The Highway Safety Manual has shown that deadly crashes can be decreased by 17% if speeds are reduced just 1 mph. A separate study from Sweden’s Lund Institute of Technology found that a 10% reduction in the average speed led to 34% fewer fatal crashes. Imagine the impact of lowering Houston’s default speed to 25 mph.

It has worked in Seattle and Boston, where lowering the speed limit to 25 mph resulted in a reduction in crashes and speeding overall. But lowering speed limits alone isn’t enough, and it’s not as effective as design.

“Without full power to redesign streets, the only way cities can influence vehicle speed is through speed limits — which isn’t as powerful a tool as design,” Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America, and Emiko Atherton, director of the National Complete Streets Coalition, wrote in an article on Streetsblog USA. “Making streets safer through design was the only way that Oslo, Norway was able to achieve Vision Zero. Without changing street designs, cities don’t stand a chance at reducing the number of deaths on their roads.”

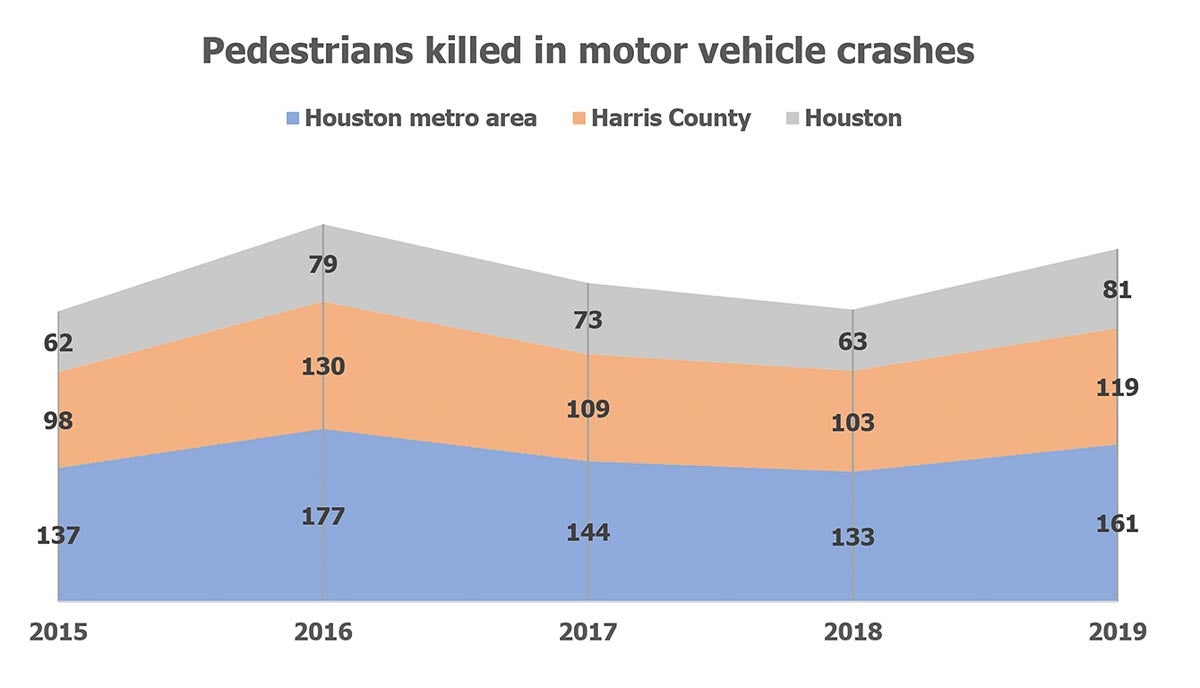

Pedestrians and bicyclists constituted 38% of all roadway deaths in Houston in 2019 — a 3% increase from 2018. Overall, 647 people were killed in fatal crashes last year in Houston, according to NHTSA data released in December. That’s a 9% increase in deaths compared to 2018, a disheartening step in the wrong direction for achieving the city’s Houston Vision Zero plan to end traffic-related injuries and fatalities by 2030.

On Tuesday, a man on a bicycle was killed at the intersection of Westheimer and Fondren in West Houston after being hit by the driver of an SUV. The driver fled the scene.

“If we wanted to design an intersection intended to repel bicyclists and maximize fatal crashes, it would look something like Westheimer and Fondren,” BikeHouston Executive Director Joe Cutrufo said in a statement released by the nonprofit on Wednesday, “where there are 16 lanes for cars and trucks, and zero for people on bikes. This type of street design is incompatible with Vision Zero and must be reevaluated as part of Mayor Sylvester Turner’s plan to eliminate traffic deaths.

“Houston has seen a concerted effort in recent years to improve conditions for cycling, but only a tiny fraction of streets in the Bayou City have dedicated lanes that physically separate people on bikes from multi-ton motorized vehicles. In order to keep up with the growing demand for safe cycling routes, and to make progress toward the goals outlined in the mayor’s Vision Zero Action Plan, the City and County need to completely reimagine their approach to street design.”

Speed reductions and street designs to calm traffic are both components of Houston’s Vision Zero action plan, which states, “We will prioritize saving human lives through street designs and safe systems (that) accommodate the inevitability of human mistakes.” The plan also calls for lobbying for state authority to set the default speed limit on residential streets at 25 mph.

Here are a few fairly recent changes to the built environment in Houston that aren’t sexy but they’re effective in slowing traffic, which should save lives and make streets safer for Houstonians.

Chicanery on La Branch

The Austin Corridor of the Houston Bike Plan runs from Buffalo Bayou to Brays Bayou along Austin, La Branch and Crawford streets through downtown, midtown and the Museum Park neighborhood. On the La Branch segment, near MacGregor Elementary School, the road design includes a speed-reducing S-shaped chicane.

The National Association of Transportation Officials (NACTO) provides this definition of a chicane: “Offset curb extensions on residential or low volume downtown streets create a chicane effect that slows traffic speeds considerably. Chicanes increase the amount of public space available on a corridor and can be activated using benches, bicycle parking, and other amenities.”

Median refuge islands in Third Ward

Median refuge islands are protected spaces placed in the center of the street to facilitate bicycle and pedestrian crossings.

In Third Ward, median refuge islands were installed at the intersections of Elgin and Hutchins streets and Alabama and Hutchins at the end of 2019 to make it easier and safer for cyclists using the bike track on Hutchins between Gray and Cleburne streets to cross Alabama and Elgin.

The median refuges islands effectively extend pre-existing medians immediately east and west of the intersections, prohibiting vehicles traveling on Alabama and Elgin from making left turns onto Hutchins and blocking traffic on Hutchins from crossing Alabama and Elgin while creating cut-throughs for cyclists, pedestrians and others.

Median refuge islands are also part of the proposed 11th Street Bikeway in the Heights, specifically at 11th and Nicholson streets, where the Heights Hike and Bike Trail crosses 11th.

Benefits of median refuge islands, according to NACTO:

► By simplifying crossings, allows bicyclists to more comfortably cross streets.

► Provides a protected space for bicyclists to wait for an acceptable gap in traffic.

► On two-way streets allows bicyclists to take advantage of gaps in one direction of traffic at a time.

► Reduces the overall crossing length and exposure to vehicle traffic for a bicyclist or pedestrian.

► Decreases the amount of delay that a bicyclist will experience to cross a street.

► Calms traffic on a street by physically narrowing the roadway and potentially restricts motor vehicle left-turn movements.

► Establishes and reinforces bicycle priority on bicycle boulevards by restricting vehicle through movements.

► When used with a protected cycle track, raised medians can be installed at each side of the block to give structure to the floating parking lane.

► When used to protect a cycle track, raised medians can provide crossing pedestrians with a refuge area and/or provide shelter for a bicyclist making a two-stage turn across traffic.

The Cullen Boulevard road diet

The bike lane on Cullen Boulevard that stretches from Polk Street to I-45, just north of the University of Houston, has been revamped. Of particular note is the segment of Cullen between Leland and the Gulf Freeway, which a road diet reduced from four lanes to two, the bike lane in both directions was widened and lined with armadillo humps, and a median refuge island connecting the student apartments on the east side of Cullen with a new development being built across the street on the site of the former Fingers Furniture store. The changes included in the 4- to 3-lane conversion are designed to slow traffic on Cullen and make the area more walkable and bikeable.