The past 14 months have been astonishing.

The U.S. is approaching 600,000 deaths from COVID-19, an astonishing total. Currently, there are three vaccines approved for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration, an astonishing feat.

New jobless claims have fallen to their lowest level since the pandemic rocked the economy more than a year ago. The latest total of 498,000 is 92% less than the peak of 6.1 million at the end of April 2020. In Texas, unemployment claims dropped by 88% compared to the same time last year. The jobs report for April of this year wasn’t as encouraging. Disappointing was the most common modifier used across news outlets on Friday in describing news from the Labor Department that the economy only added about a quarter of the 1 million jobs economists had expected.

“The Fortieth Year of the Kinder Houston Area Survey: Into the Post-Pandemic Future”

For the past four decades, Rice University’s Kinder Houston Area Survey (KHAS) has been tracking systematically the continuities and changes in the attitudes and beliefs, opinions and experiences of Harris County residents. The results of the 2021 survey and the full report are now available.

Despite the setback, the economy is showing signs of recovery. There’s still a long way to go before it returns to pre-pandemic strength, but the nation is starting from the bottom of an unusually deep hole. Climbing out of it may just be slower going than some first thought.

While the past few months have brought encouraging news that the nation’s economic recovery is underway, the good news is relative. It doesn’t apply to every American and may not bolster future confidence among the 9.7 million workers who lost their jobs because of the pandemic and are still unemployed. The past 14 months, of course, have exposed and worsened a litany of inequalities that have plagued the U.S. for far, far longer than 14 months — overwhelmingly afflicting people of color. Sadly, it took a pandemic and the video of a Black man from Houston being killed by a police officer on a street in Minneapolis for many in America to acknowledge the country has deeply rooted problems with race.

Inequalities, including the pandemic’s disproportionate impact — both financially and in terms of infections and deaths — on Hispanics and African Americans, and the prevalence of racism in the U.S., were two of the issues highlighted by key findings in “The Fortieth Year of the Kinder Houston Area Survey: Into the Post-Pandemic Future,” by Kinder Institute Founding Director Stephen Klineberg and Robert Bozick, associate director of the survey. Interviews for this year’s survey were completed in January and February — before Winter Storm Uri blasted the state.

Each year, when the survey is conducted, Houston-area residents are asked to name the biggest problem facing the region. Since 2013, the dominating concern has been traffic congestion, cited by 30 to 35% of respondents to the survey. After traffic, around 15% of residents typically answered crime and the economy (13%). In 2018, following Hurricane Harvey, 16% said flooding was the biggest problem — second only to traffic.

This year, only 13% of respondents cited traffic. Unsurprising considering the dramatic transition to working from home that took place at the start of the pandemic. More than half of Americans continue to work from home at least part-time. For 14%, crime was the main concern, while 20% saw the economy as the biggest problem. The COVID-19 pandemic and public health issues more generally were the No. 1 concern, cited by 25% of respondents. Until this year, public health was hardly mentioned at all by survey respondents.

Inequalities were a dominant theme of the 2021 report

While it’s not at all surprising that people getting sick was named as the biggest problem in Houston, but, Klineberg says, “it reminds us that (public health) is still the preoccupation in Houston even as we’re coming out of this yearlong pandemic and this yearlong lockdown and we’re beginning to look beyond the pandemic and move back toward something more resembling normality.”

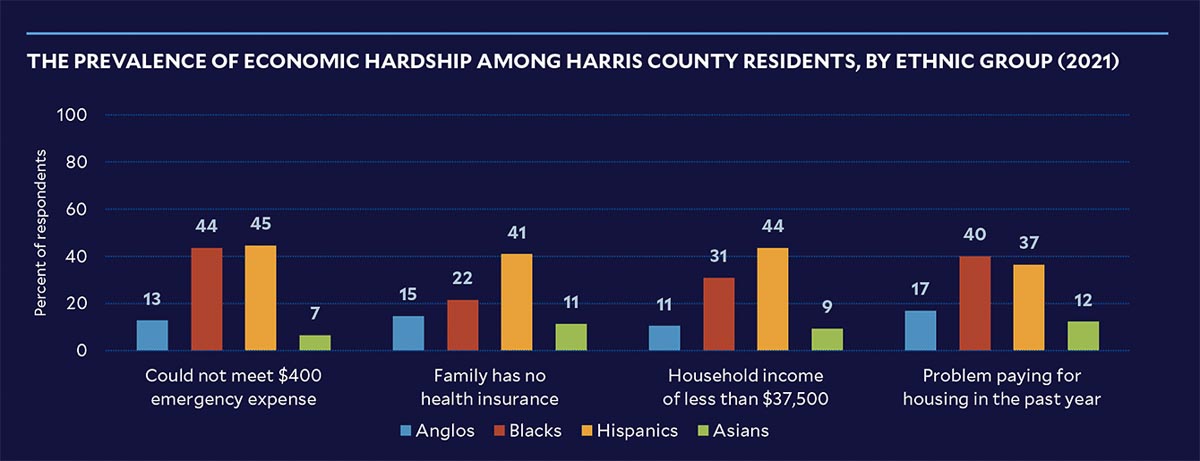

At the same time, one in four Harris County residents said they didn’t have health insurance, and more than one-third of survey respondents said that if confronted with an emergency that cost $400, they wouldn’t be able to cover it.

In addition to hardships like these, more than one-fourth of residents said they had trouble paying for housing. The lack of basic resources such as these was much worse for Hispanic and Black residents compared to Asian American and white or Anglo residents. Faced with that $400 emergency, only 13% of white and 7% of Asian residents said they would either have to borrow the money or couldn’t come up with it. That’s compared to more than 40% of Black (44%) and Hispanic (45%) residents who reported not having the savings to pay for an unexpected cost.

An emergency could be a broken-down car or a busted refrigerator; it could also be a sick child or spouse.

Texas has the highest rate of uninsured (18.4%) residents in the nation. In Houston, 16% of children have no health insurance — one of the highest shares of uninsured children among major cities. That’s despite Houston having “one of the greatest conglomerations of medical institutions in the world,” as Klineberg and Bozick point out in their report. “Being without insurance means having far less access to early and effective medical treatment.” Among the respondents to the Houston Area Survey, the rate of uninsured ranged from 11% of Asian and 15% of white residents to 22% of African Americans and 41% of Hispanics.

“(The inequalities are even more alarming) when you couple that with the realization that 70% of everyone in Harris County under the age of 20 — who will be the workers and voters and citizens and taxpayers of Houston in the 21st century — are African American and Latino,” Klineberg says. “The two groups overwhelming most likely to be living in poverty. That’s going to be our future.”

These and other disparities have shown up in previous editions of the survey, but the threat they pose was magnified by the yearlong pandemic.

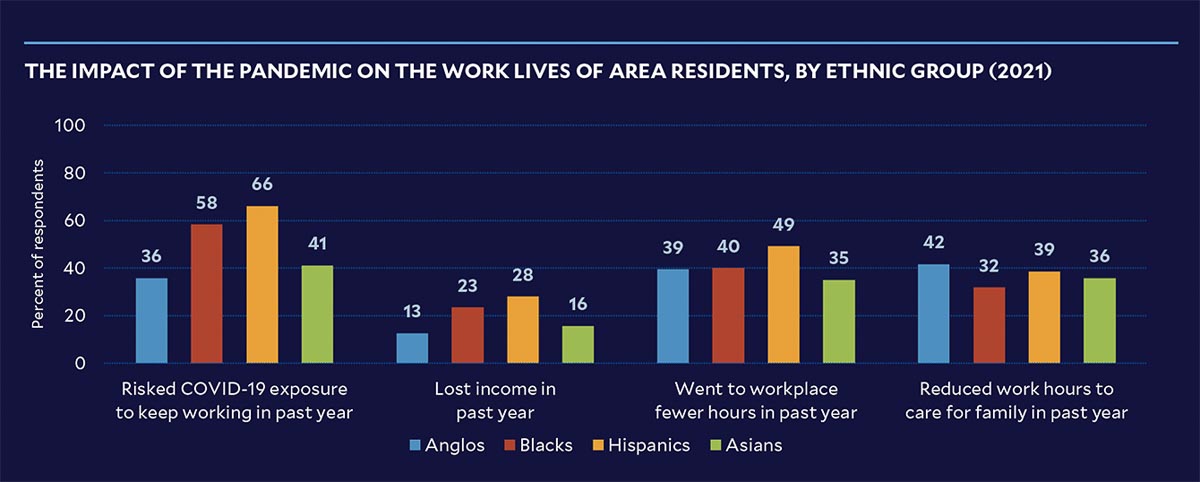

An overwhelming majority of Black residents — 73% — knew someone who died or was hospitalized because of COVID-19. Two-thirds of Hispanic residents did as well. Black and Hispanic residents, who are more likely to be frontline workers, were also more likely to have risked being infected to keep working during the pandemic — 58% and 66%, respectively, compared to 36% of white residents and 41% of Asians.

African Americans were more likely to have received assistance from government programs or social services to help in coping with the pandemic than other area residents (21% compared to 14% overall).

“It’s just extraordinary how much more vulnerable Black and Hispanic residents are, compared to the Anglos and Asians living in Harris County,” says Klineberg, who began what would become the Kinder Houston Area Survey as a project with his sociology students at Rice University in 1982. “And we did the best we could for as many years as possible to basically say, ‘inequality is not real, and everyone has the same opportunity in America, and that government has no role to play in this.’ And I think there has now been a real recognition that this is untenable and that this is unsustainable.”

A reckoning in the wake of George Floyd’s murder

One of the more striking results of this year’s survey, according to Klineberg, was the increase in the percentage of Anglos and Hispanics who said Black residents are often discriminated against in Houston.

“Not only that new awareness of discrimination against Black residents, but a broader awareness that people are poor in this country through no fault of their own, and that government has a critical role to play in economic justice.”

Two-thirds of respondents to the 2020 survey said that most poor people in the U.S. are poor because of circumstances that are out of their control. This year, that increased to 80%. And 85% of respondents reported that they thought the government has a responsibility to reduce inequalities, while almost 60% maintained the government should do more to solve the country’s problems — far more than in previous years of the survey.

In general, the view of ethnic group relations was lower this year than in the past. Overall, only 43% of respondents would rate the relations among racial or ethnic groups in the Houston area as positive (“excellent” or “good”). A drop-off compared to 55% in 2020. Among white residents, the positive rating dropped from 70% to 54% in just a year.

Black respondents’ assessment of relations among ethnic groups declined as well, from 30% saying relations were “excellent” or “good” in 2020 to just 25% in 2021. “This was by far the lowest percentage of positive evaluations given by any ethnic community to interethnic relations in Houston across all the years of the surveys. The deepening concerns about racial justice during the past year clearly have influenced the assessment of ethnic relations across all groups,” wrote Klineberg and Bozick.

The killing of George Floyd, who grew up in Third Ward, was also a Houston event, says Klineberg. And that’s reflected in the responses from Houston-area residents in this year’s survey. In 2020, he adds, one thing that appears to have penetrated the consciousness of Americans, particularly whites and Hispanics who have in the past tended to resist saying Black people in American are especially discriminated against, is the recognition that, indeed, that is the case.

“That was a really powerful event,” Klineberg says, referring to the video of former police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes. “We’ve never seen anything like that before. So, (the survey responses are) a reflection that we have been changed by that experience.”

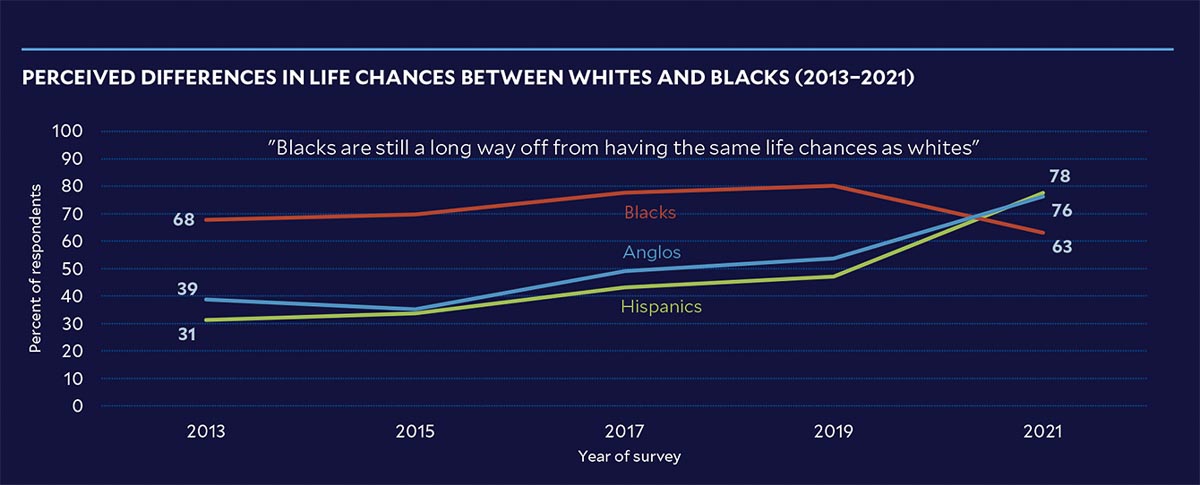

When asked if they agreed that “Black people in the U.S. are still a long way from having the same chance in life that white people have,” the share of Anglo residents who agreed went from 54% in 2019 to 76% this year. Among Hispanics, it increased from less than 50% to 78%. Across all ethnic groups, the percentage of respondents who agreed this year was 66% — up from just 52% in 2019. The same question has been asked every other year since 2013, and the number of participants who agree has gone up slowly each year, but nothing close to the increase seen from 2019 to 2021.

“I think that reflects the fact that it’s clear there are real inequalities here, and the inequalities are not just economic, but also ethnic and racial,” Klineberg says.

Among Black respondents, however, the percentage of those who agreed that African Americans are at a big disadvantage compared to white Americans, decreased, from 80% two years ago to 63% this year.

Optimism about economic recovery

In 2011, the year after the Great Recession ended, optimism about job opportunities in the Houston area was at 35%, according to that year’s Houston Area Survey — the lowest level seen since 1993. By 2014, positivity about jobs was back above 60%, where it stayed for the next seven years.

In the 2020 Kinder Houston Area Survey, 68% of Houston-area residents gave positive ratings to job opportunities in the region. Shortly after the final interviews for last year’s survey were completed, the local economy was basically shut down to help slow the spread of COVID-19.

Though there was a decrease in the share of survey participants who appraised job opportunities in the region as “good” or “excellent,” the drop was only seven percentage points, which Klineberg says was “somewhat smaller than expected, but still a reflection of the yearlong recession from which the city is now slowly recovering.”

From 2016 to 2020, roughly one-third of Harris County residents taking part in the Houston Area Surveys reported that their financial situation had been “getting better” during the previous three years. But this year, only 21% reported that their financial situations had been improving, a 13% drop from 2020. It was the first time in 40 years that more residents said their financial situation was getting worse than better — 25% compared to 21%.

At the same time, the 2021 survey found 57% of area residents thought they would be better off three or four years from now, which, statistically, is the same as the 56% in 2020 who were optimistic about the future.

The widening partisan divide

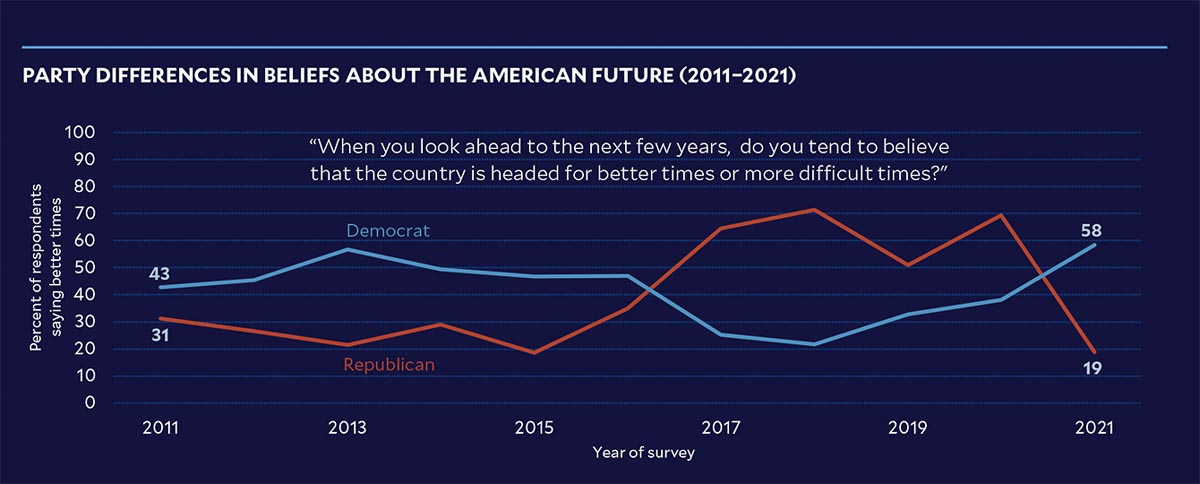

In past surveys, when asked if they believed that the country was headed for “better times” or “more difficult times,” responses have shown a clear partisan divide.

“During the Obama years, Democrats said the country was headed for better times,” Klineberg says, “while the Republicans said more difficult times. During the Trump years, it was reversed.”

After the election of Joe Biden, the number of Republicans who thought the U.S. was headed for better times dropped by 50 percentage points — from 69% at the beginning of 2020 to 19% after the November 2020 election. Among Democrats, a similar — though smaller — about-face occurred after Biden’s election, with a 20% increase (from 38% to 58%) in the number of Democrats who said better times were ahead. That 39-percentage-point gap between Democrats and Republicans about where the U.S. is headed is significant but it isn’t the widest separation seen in the past few years of the survey.

That distinction belongs to the results of the 2018 survey, which found 71% of Republicans affirming the country was headed for better times, compared to just 22% of Democrats. That almost 50-point gap is the largest Klineberg has seen on that question.

“More than ever, it seems, our experience of the world and our expectations for the future are a function not just of the objective realities but also of the ways those realities are filtered through our political orientations,” he and Bozick write in this year’s report.

Bipartisanship has become a rarity within the polarized political system in the U.S. That’s true at the national level in Washington as well as the state level, where tensions run high between red states and blue cities. And this sharp divide along party lines isn’t new. The “golden age of bipartisanship” that existed in the 20th century ran its course a long time ago.

Today, ideology drives the binary reality of politics, and with partisan divides only growing, it’s uncertain if hoping for bipartisanship’s return is an effective strategy. Klineberg and Bozick don’t serve up solutions in the Houston Area Survey. As Klineberg has done each year for the past 40, they only interpret the results, summarize the most consequential changes and ask about their implications for public policy initiatives and policymaking going forward.

Will regional civic and business leaders and policymakers use this information about the evolving attitudes of Houston-area residents and make the “collective and sustained investments” needed to ensure the continued prosperity of the city? That remains to be seen, the authors say.