“You betta do somethin’."

Those were the words of Ms. Courtney as she warily watched her new neighbors move in. They spoke of being artists and were cleaning up the block she had called home for many years. This block in northern Third Ward had gone through various phases over the years — some good, and in more recent years, some increasingly challenging. It was 1993, and while the neighborhood remained rich with culture, history and spirit, it had become riddled with economic challenges and crime. This was a result of various factors — from the impact of integration in the 1960s, which shifted the once economically diverse community, to the influx of crack cocaine in the 1980s.

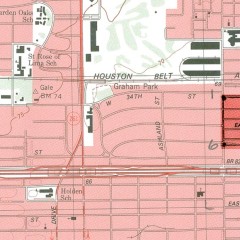

Ms. Courtney had witnessed bright-eyed groups come through the block claiming to intend to improve the once safe and economically thriving community. She had also watched many of them give up and leave, and others who were simply there to make a profit. The threat of gentrification was at every turn and corner, from Gray Street to Alabama Street.

So she had great reason to be skeptical of these new neighbors: Who were these artists, what were their intentions and what would make them different from all of the others?

They were seven artists — Rick Lowe, Jesse Lott, Floyd Newsum, James Bettison, Bert Long Jr., George Smith and Bert Samples. When I spoke with Samples this May, he reflected on Ms. Courtney’s demand, and he agreed that she indeed had much reason to be skeptical, because for her, only time would tell. They could have been just like the others. Except they were not. They were more than artists. They were seven African American artists with vision.

With many of them being mentored by world-renowned artist Dr. John Biggers, the founder of Texas Southern University’s art department, and community activist Deloyd T. Parker, one of the founders of S.H.A.P.E. Community Center, their goal was to transform a row of houses on Holman Street and to, in turn, allow this energy to radiate throughout the entire community. They used influences from Biggers’ artistic works and research, which highlighted the South’s historical row house architecture as a continuity of African culture, along with German artist Joseph Beuys’ concept of the social sculpture to transform the houses into homes for art. These installation spaces not only represented art, but most importantly culture, positive intention and action to revitalize and preserve the Third Ward.

Project Row Houses sought to raise awareness around and combat the community’s challenges, including gentrification, poverty and drive-by shootings. In fact, its earliest artist installation round, “The Drive By,” was centered on these themes, rooting the organization in social practice art.

Over the years, these artist rounds have continued to highlight African American artists and themes impacting their communities, with some of the more recent rounds covering topics ranging from Black maternal mortality to critical race theory.

Their work did not stop there. Many community-centered programs have been birthed out of the original mission of the founding artists over the years, with the questions raised by the art heightening and expanding the organization’s efforts. These include the Young Mothers Residential Program, community housing, small business incubation and, most recently, the Third Ward Cultural District and the Financial, Artistic, Career and Empowerment Center (FACE Center). All of these programs have been designed to revitalize and sustain Third Ward.

As an incubator space, Project Row Houses has nurtured businesses such as All Real Radio, which is celebrating its ninth anniversary this year; Crumbville, TX Bakery; Ujima Residents Resource House; NuWaters Co-op; and the bookstore Kindred Stories, which have supported the Third Ward community. The Emancipation Economic Development Council (EEDC) was also incubated at Project Row Houses along with Sankofa Research Institute under the leadership of Dr. Assata Richards. It has gone on to support dozens of Black-owned businesses and business owners based in the Third Ward.

Project Row Houses has also been instrumental in restoring historic buildings, such as Delia’s Lounge and the Eldorado Ballroom. Acquired through real estate broker Herman Gary Jr., Delia’s was once a Great Depression-era speak-easy and is now home to Crumbville, TX. The Eldorado, a social haven opened by Anna Johnson Dupree and Clarence Dupree in 1939 to provide a safe, classy and exciting place for African Americans in the Third Ward to dance and celebrate during the Jim Crow era, was comparable to Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom and Club Matinee in Houston’s Fifth Ward. It was gifted to Project Row Houses in the late 1990s, and after four years of renovations, the building reopened its doors this past May, just shy of the organization’s 30th anniversary.

It is now July 2023, exactly three decades after the founding of Project Row Houses, and nine years after I was first introduced to it. I started off as a docent and have since been involved in various capacities, from being on the team that helped create the EEDC and as an Artist Thought Partner for the development of the FACE Center to being an artist in Round 50 (“Formed in My Grandmother’s Womb”) and partnering with the organization for my nonprofit’s summer program The Re-Education Project. But what stands out the most is how Project Row Houses has held me and valued me along my journey — how it saw something in me in 2014 before I even saw it in myself. How it welcomed me as a community resident and helped me to recognize myself as the artist that I am, which unlocked potential that I did not know existed. It showed me what it looks like to use art to transform communities with care and intention. Project Row Houses is not just valuable because of how it transforms spaces but how it has transformed countless lives, including my own.

And so, 30 years later, time did tell. Perhaps the founders did not know then that Ms. Courtney’s call to action — her demand — would make activists out of them and would lead to the creation of an internationally recognized organization. But what is clear now is that Ms. Courtney’s demand was truly a manifestation over the lives of those seven visionary African American artists, the 39 buildings that have been restored and built, all of the residents of Holman Street whom their legacy has transformed and those they have inspired around the globe. They have indeed done something.

The mission of Project Row Houses’ founders has not only been achieved, but it continues to be carried out under the leadership of Executive Director Eureka Gilkey and its dedicated staff and board. In celebration of 30 years, they have honored the original round with “The Drive By II,” in addition to a host of commemorative festivities and programming.

We do not know exactly what the next 30 years will bring, but we can be sure that Project Row Houses will continue its mission of empowering people and enriching communities through engagement, art and direct action, as it has so faithfully done since 1993.

Lindsay Gary is a multidisciplinary author, artist and scholar based in Houston. She has master's degrees in dance, history, and public policy, and a Ph. D. in Africology and African American studies.