The book came to life with the support of the artist-in-residence program at The Printing Museum, which also served as the publisher. A Houston artist and scholar with deep roots in the city, Gary spoke with the Urban Edge blog about the book and the impact she hopes it will have.

The interview has been condensed and edited.

We have to start by talking about you because this book is clearly a passion project. What would you say is this book’s origin story?

I'm from Houston—born and raised in Third Ward, and I still live here in the neighborhood. I grew up in a very amazing environment. My parents and my grandmother raised me, as well as other family members in my “village”—extended family, friends and other people. I grew up very aware early on of our history here in Houston, because of those people, especially the elders I was around.

My parents instilled the value of education, especially Black history. We were watching “Roots” at 3 and 4 years old, I'm not even exaggerating. We had a strong understanding of where we came from. And it was very much reiterated through the people around me in that village about why it's important to be aware of those things.

I see the book as an extension of what I grew up with. If you already knew me and my family, it wouldn’t be surprising that I did something like this. It was something that was already in me ever since I was born. They say I came here like that.

I've always had a passion for history. I love to travel; I've been to 37-38 countries around the world. A lot of my travel has been to diasporic places and obviously to Africa, as well. I really found it beautiful to go to these places and learn about the connections we have with Black people in different parts of the world. I also lived in Philadelphia for about six months, when I was starting my Ph. D. program. There, everywhere you go, somebody is going to tell you, “Oh, that's a historical site, that's this place and that place.”

But I found that it was really hard to find these things in Houston. And when I would be talking about historical places in Houston, Black historical places and cultural sites, a lot of people didn't know what they were, unless they had the kind of upbringing that I had, or were a part of that community.

I thought there should be a resource that makes it simpler to find and see these places, a way to help to increase the awareness of what is around us in Houston. So that was the beginning of the idea.

Before I got to Philly, I had already published a short article about some of the historical sites in Houston. But I was thinking, “OK, we have to really expand this. That article was too short, so maybe it could be a book.”

So at about this time, you come to be part of the Printing Museum’s artist-in-residence program? How did that come into play?

Yes, so by then I had started roughly outlining it, and when the artist-in-residence program was taking applications in spring 2020, I sent them a proposal. They said, “This is a great proposal. But we don't know that we have the capacity to see it through” — it was a lot of work and would have taken longer than the residency program itself.

I was thinking they were saying no. But they sent another email saying, “We want you to reapply after you've done the interviews for the book. That way, you will be able to complete the project within the set timeframe.”

So I did that, and in the next round, I reapplied, and they said, “We still don't think this project will fit into this timeframe and our structure. But we’re going to create a new program just for you. You're going to be a writer in residence and carry out this project.” And it was perfect, exactly what I needed.

I'm so appreciative that they believed in what I was doing because it was ambitious. I was surprised—obviously, I thought it was a good idea—but they saw the importance of doing it and really committed to seeing it through with me.

So some of the work had been done at that point, but obviously, there was more to be done. How did you go about building your list of sites and researching?

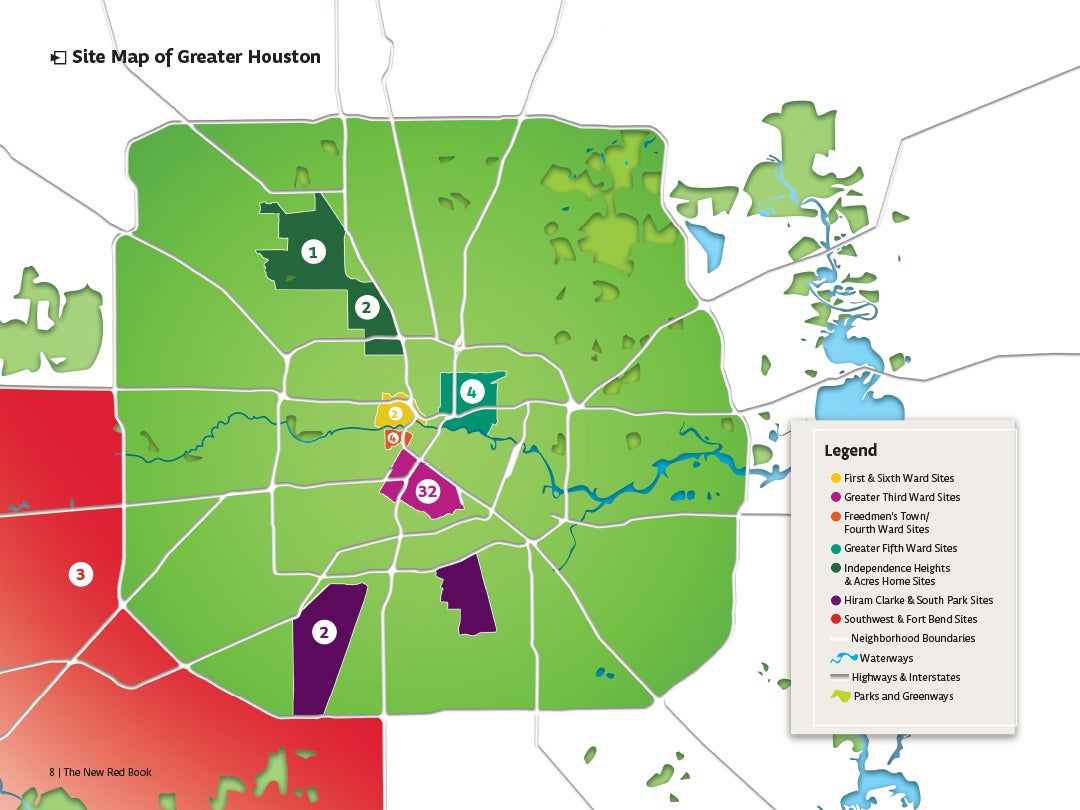

Initially, I didn't really have a set structure, a set amount or categories—it was “that’s a park,” or “that’s a church.” But very quickly I realized the need to be intentional and focused because there are so many. So let's think about the places that have made a major impact and are still in existence, because I think that's one way I could reasonably limit it, otherwise I would be going on forever. We just didn't have that capacity.

I started with what I knew, then started doing interviews. I reached out to people, not necessarily always the people who own or manage the locations but also family members and people I know in the community. As you do the research, and as you are involved in other things, more things emerge. For example, I was involved with “Memory Builds the Monument,” a short documentary about Club Matinee, a historic club that was very well known. (Gary’s distant cousin, Jean-Baptiste “Illinois” Jacquet, played the city’s first concert with an integrated audience there in 1955.)

Well, I had never heard of that before. Unfortunately, that building is no longer there, so it’s not in the book, but this led me to other sites. I did another project with Fresh Arts and Arts District Houston, with my dance company, Dance Afrikana. We were commissioned to do a kind of historical dance piece on Brock Park. What is that? Turns out it was named after a historical Black figure, Richard Brock, who I had never heard of. There are a bunch of places like that.

Houston builds and builds; we tear down, and we often don’t look back. But it's less preserved when it's Black history. So much has been lost or is threatened to be lost as Houston changes. In a way, this book acts as a countermeasure to that. It calls out the things that we have not lost—yet. What do you hope people do with it?

We do want people to go to these places because it's one thing to know a place exists, but are you going to support them? Because they need the support. Most of these places, people can go visit, and they should tell their friends and family, because they're really gems of the city. I would love to see people spend 2023 visiting each one of these places. I would love that. I mean, there are 50 sites; there are 52 weeks in a year.

I also really hope that it's a wake-up call to not tear down any more of these historic and cultural sites. There are so many that were lost, it’s so sad. Can you imagine how many more sites there were, you know, just 50-60 years ago? It would fill up another book.

I would love to see people really use this book as a tool and not just a book to have on the shelf. I want it to be a tool of information. I would love for children to have this in their classrooms, you know, libraries to have it. I want as many people to read it as possible and to support the things in it. And actually, the book ends with a section on ways you can support this history.

I’m sure there are many—at least 50—places you think people should visit, but are there a few that stand out in your mind or that are close to your heart?

There are so many! Shape Community Center. The SAiD Pan African Library. DeLuxe Theater. Texas Southern University. Project Row Houses is very special, and it’s one of my favorite places in the city. I used to be a docent there when I was in grad school, and I credit them with helping me to see myself as an artist.

People don't think of a cemetery as the first place to go, but Olivewood Cemetery is up there. It represents a very powerful legacy in terms of being a close, visible connection to African culture in the way that the graves are designed and being one of the earliest incorporated Black cemeteries in the city. The names that we know, that's where they're resting. But Olivewood also needs that attention and support. They need help.

Doing this work, learning about what has been lost, and learning more stories from Houston’s past, must have been an emotional journey. How did it affect you?

It was hard. First, this is my first major publication. So it just took a lot of mental capacity to see it through. Sometimes I wouldn't hear back from people, you know, and just that can be discouraging. Even though it's a pretty small book, it took a ton of research. Every site is a story.

I had to really keep the end goal in mind. I had to remember, you know, the ancestors would be saying to me, “Girl, you better finish that book. We’re trying to speak and tell our stories.”

This is, for me, one of the most important things I've ever done. And it's really bigger than me.

The title, “The New Red Book,” is a reference to the original Red Book from 1915. It is one of the most comprehensive snapshots of Black life in a major US city of the time. What role did that book play in your work?

When I was doing the research, I had no idea about The Red Book. It was not until I was almost done with most of the writing that we learned about it. No one knew about it.

But once I did learn about it and was able to read it, there were all these things. I was just blown away, which is why I wanted to honor that history by calling this the “New” Red Book, so then people can also learn about the original. And I have to thank those ancestors for doing that work, it was so amazing.

It was really divine. It made me feel even more connected to the city. I've always been a Houston girl, but it just gave me that deeper connection to the land and made me a proud recipient of all the amazing things that they laid down for us.

Thinking about that book makes me super emotional. The book itself, and also the way I came across it, I'm just thankful that I did. I don't think that I would change anything about my book had I known about it sooner. I'm just glad I changed the title to reflect that this book existed. And now, maybe many more people will know about it, too.