In the weeks leading up to last year’s Juneteenth celebration, Tanya Debose knew she wanted to do something special to mark the date in 1865 when word of the Emancipation Proclamation reached Texas—nearly three years after President Abraham Lincoln’s executive order ended slavery in America. In the wake of the killing of George Floyd on Memorial Day 2020, Black Lives Matter protests calling for an end to police brutality and racially motivated violence against Black Americans were taking place across the nation.

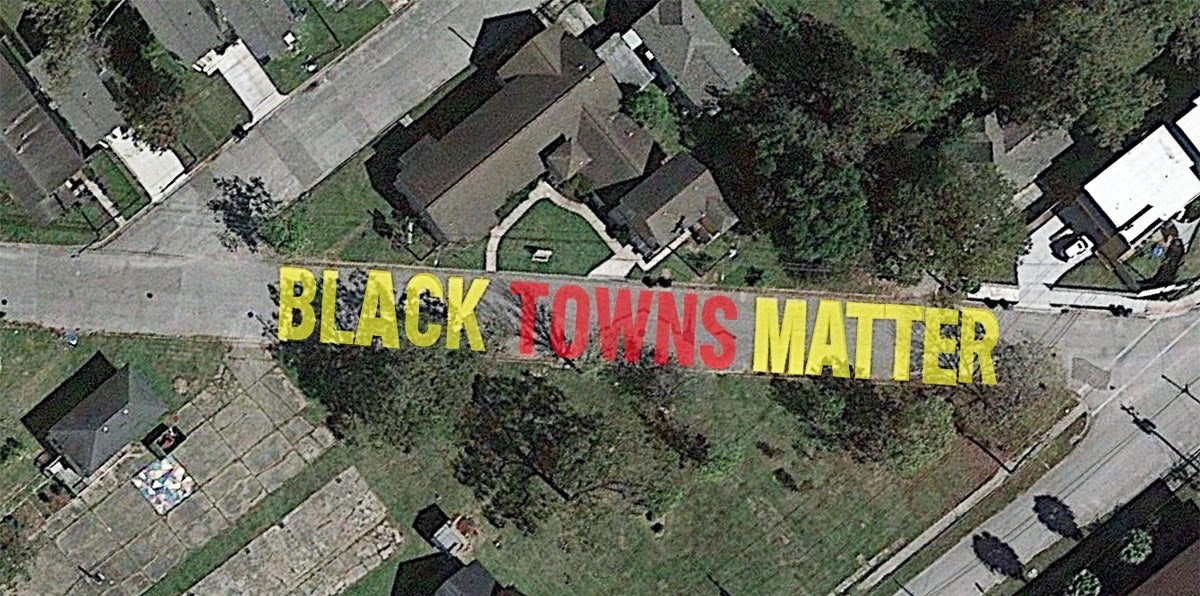

Inspired by the “Black Lives Matter” mural that Washington D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser had painted on 16th Street NW in front of the White House, Debose had the idea for a “Black Towns Matter” mural to be painted on the stretch of Link Street between East 34th and East 33rd streets, in front of the Green Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Independence Heights. Juneteenth, which is also known as Emancipation Day, was the rollout date for the Black Towns Matter initiative, a public art project to build awareness of the more than 1,200 Black settlements and towns established in the U.S. after the end of slavery.

Independence Heights is one of only 50 or 60 Black towns in the U.S. to be legally incorporated as a city, and the first in Texas. Other historic Black towns and settlements include Prairie View, Grambling, Louisiana, Mound Bayou, Mississippi, Hobson City, Alabama, and Eatonville, Florida—the historically Black incorporated hometown of Zora Neale Hurston.

“We didn’t want to look back 20 years from now and go, ‘Where were we in this moment?’” says Debose, who is the Executive Director of Preserving Communities of Color and the Independence Heights Redevelopment Council. “In this George Floyd moment with Black Lives Matter being at the forefront, how do we tell the story of Black towns?”

Independence Heights, Debose says, is her identity: “It’s who I am.” Her great grandfather, whose father had been a slave, moved from Wharton to Independence Heights, where he was able to buy a home in 1924. That wasn’t something African Americans could do in many Houston neighborhoods during the Jim Crow era.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the Wright Land Company established Independence Heights on land six miles north of downtown Houston. Wright marketed the community to African Americans, who at the time weren’t able to get approved for conventional bank loans, selling lots as well as offering low-interest financing on the construction of new homes. Wright’s clients could pay as little as $6 for a monthly mortgage note.

By 1915, the community had grown to around 600 residents; and in January of that year, they voted almost unanimously in favor of incorporating, with only two votes cast in opposition, the Houston Post reported at the time. City improvements over the next few years included the “shell paving of streets, plank sidewalks and the installation of a municipal water system.”

In 1928, residents voted to dissolve the city’s incorporation and become part of Houston, with the hopes of better city services. Houston annexed the area the day after Christmas 1929. The improvements, however, didn’t materialize: In 1940, only about 23% of Black households in Houston had running water. By comparison, 95% of non-Black homes had water service. In addition, Black neighborhoods were often in need of paved streets, street lights and adequate drainage.

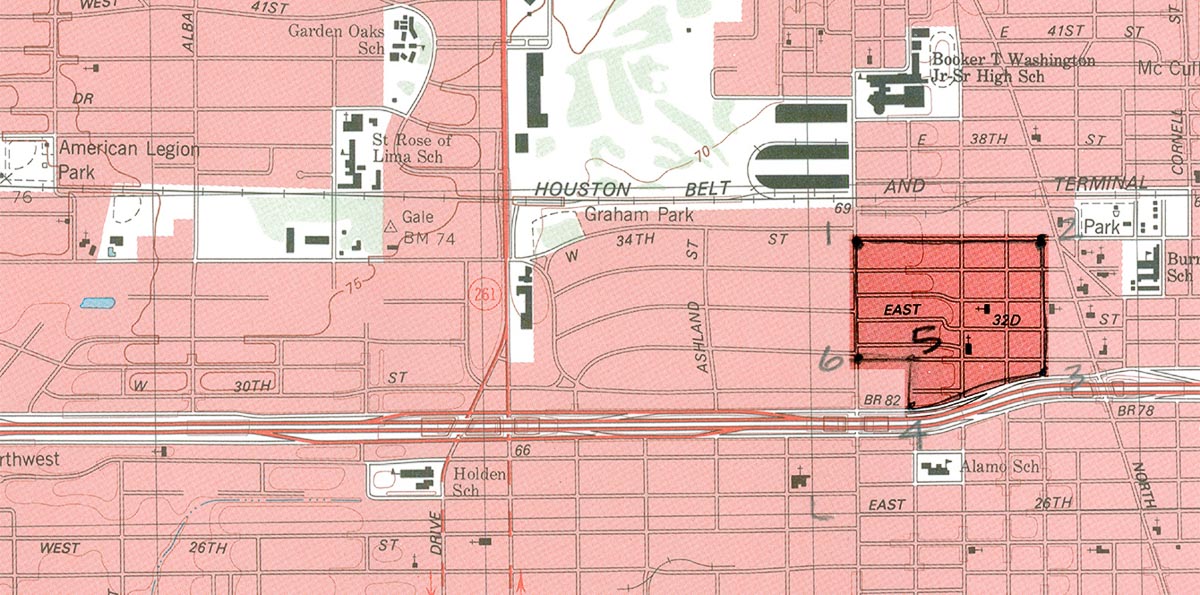

Like a lot of communities of color, Independence Heights was underserved throughout the 20th century, weathering years of neglect and crime. Over the years, parts of it have been displaced by gentrification and eaten away by highway construction. In 1959, for example, the home Debose’s great grandfather bought on 30th Street in 1924 was among those demolished to make way for Loop 610. If it wasn’t for the diligence and relatively thankless work of those who refused to let Independence Heights be forgotten, it’s unclear how much of the community would be preserved today. In 1997, the Independence Heights Residential Historic District (70 acres of land roughly bounded by Yale, Columbia, E. 34th and Loop 610), along with five other historically significant homes in Independence Heights and Independence Park were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Fighting to preserve Black history

The National Register of Historic Places lists 290 entries for Houston. Of those, 13 are places related to the experience of Black Americans—roughly 4.5%. That’s an overwhelmingly small percentage, yet it’s more than twice the share of historic sites nationwide—just 2%—that are focused on Black history.

Writer Casey Cep dove into the history of historic preservation in America and the work of activists and preservationists to change the types of places that are protected in a February 2020 New Yorker piece titled “The Fight to Preserve African-American History.” That history includes the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act, which established the National Register of Historic Places and set the standards for the National Historic Landmarks Program, as well as the biases that are baked into the criteria for selecting sites for preservation, which have favored white Americans.

One of the criteria for preservation is architectural significance, meaning that modest buildings like slave cabins and tenement houses were long excluded from consideration. By the time preservationists took notice of structures like those, many lacked the physical integrity to merit protection. Destruction abetted decay, and some historically black neighborhoods were actively erased—deliberately targeted by arson in the years after Reconstruction or displaced in later decades by highway construction, gentrification, and urban renewal.

When communities of color weren’t able to rely on state and federal institutions to help protect historic areas, Cep explained, they began protecting them themselves.

For example, in 1917, the National Association of Colored Women raised money to pay off the mortgage on Cedar Hill, a home in Washington, D.C., belonging to Frederick Douglass. Fifty years later, artist Joan Maynard led a group of Black women in saving what was left of Weeksville—"an antebellum free-black community in Brooklyn that was started by the longshoreman James Weeks in the early 19th century,” wrote Cep, who cited other examples, including the 1998 addition of Eatonville, Hurston’s hometown, to the National Register.

A few years ago, Andrea Roberts, an assistant professor of urban planning at Texas A&M University, launched the Texas Freedom Colonies Project to “map the unmapped Black settlements of Texas.” Roberts uses freedom colonies as a broad reference that includes “Black settlements, Black towns, enclaves or freedmen’s towns.”

More than 550 freedom colonies were established in Texas between the end of the Civil War and the 1930s. Many of them were located in rural and unincorporated areas. But because they were unmapped, they were mostly invisible. When it comes to capturing the history of Black settlements, “it’s a race against time,” Roberts told American Planning Association’s (APA) Planning magazine.

Black-owned lands were often taken via auctions, partition sales and theft, she told Planning, making data collection and heritage verification a significant challenge. In addition to the inequalities created by years of racist policies related to housing in the U.S., historically Black communities like Independence Heights are now also contending with what Debose calls “self-serving investors and developers” who are making preservation in Houston increasingly difficult.

“For so many years, we, as Black people, were forced to have to listen to history that didn’t include us in schools,” Debose told the Houston Chronicle in 2019. “And so now, we’re uncovering our truths. We are going back, and we’re digging it up. But the race that we are up against is the fact that our environments are disappearing and the evidence is in this environment.”

The competitor in the race that Debose referenced is the new, fast-paced development—largely detached townhomes—that has been so commonly seen over the past 15 years in communities of color near Houston’s urban core. What began in Shady Acres and portions of the Greater Heights to the south of Independence Heights eventually crossed the 610 barrier as developers continued to feed the appetites of younger, college-educated residents who wanted homes closer to the amenities of the city but couldn’t afford the prices in Montrose, the Heights or the Museum District. By buying older single-family homes to tear down and replace with two or more new, three-story townhomes, developers could easily recover their investment many times over. Similar patterns of development have been seen most infamously in Fourth Ward and in Third Ward, along a strip of land between Highway 288 and Emancipation Avenue, but also in Fifth Ward and across the area east of downtown, from the Eastex Freeway to Second Ward and Greater Eastwood.

“We definitely welcome change, but we want change that doesn’t displace the existing residents,” Debose says. “And, unfortunately, in Houston, you don’t have a lot of options or tools in terms of planning and how communities are redeveloped that can be used to stave off unsolicited development that comes in and tears down historic homes.”

Last Juneteenth, a “Black Towns Matter” mural was painted on the stretch of Link Street between East 34th and East 33rd streets, in front of the Green Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Independence Heights.

Google Earth Pro image

Holding on to history in Independence Heights

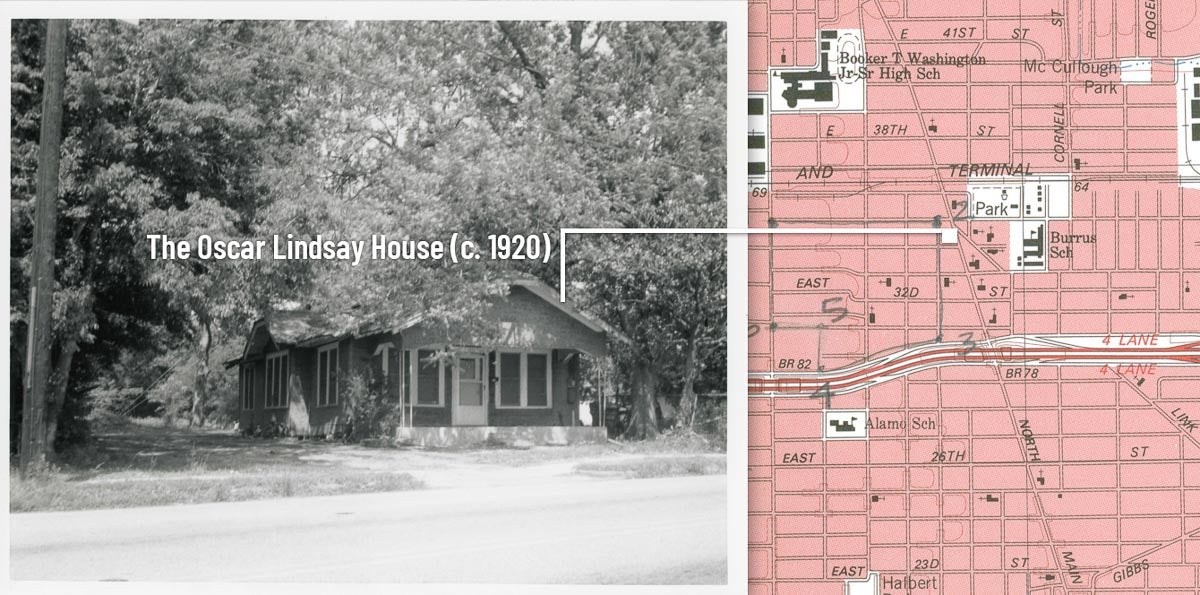

When the “Black Towns Matter” mural on Link was completed, it featured a portrait of George O. Burgess, the first mayor of Independence Heights, as the “O” in “Towns.” Just around the corner from Green Chapel AME is the Oscar Lindsay House (7415 N. Main Street), which was built in 1920. In the National Register of Historic Places Registration form, which Vivian Hubbard Seals prepared with assistance from Dwayne Jones of the Texas Historical Commission back in the 1990s, the house is described as “a 1-story bungalow rests on a foundation of concrete piers and is covered with a large gable roof of asphalt shingles. The front and side are distinguished with jerkinhead gables. Commercial, institutional, and residential uses surround the house reflecting the typical mix of activities in Independence Heights. Mature deciduous trees and planting shade the house and front and rear yards. A graveled driveway leads from the street to the rear of the property along [the] southern side of the lot. Access to the primary entrance is under an inset porch supported by two decorative iron columns set on a concrete foundation.”

Throughout her descriptions of the modest—but nonetheless historic—one-story, bungalows and L-shaped and shotgun cottages she fought to preserve in Independence Heights, Seals applies a historian’s keen eye for detail, but her objectivity isn’t impermeable, and her affection for this community and its history seep through. In 1911, the Independence Heights School was established and Seals’ father, O.L. Hubbard, became the city’s first teacher. Hubbard also served as the city’s second mayor, from 1919 to 1925.

Photo by Vivian Hubbard Seals

This is a portion of the “Statement of Significance” in regard to Oscar Lindsay’s house:

“The Oscar Lindsay House is near the center of Independence Heights on North Main Street and the home of local businessman and city official. Lindsay operated a number of small businesses in the community including a cleaning and pressing shop, barbershop and ice cream parlor. He set up and managed the ice cream business in his front yard thereby taking advantage of the location on the community’s busiest thoroughfare. In addition, Lindsay served as the city plumber for Independence Heights providing an essential service to local residents. This position was one of three public workers supported by the City of Independence Heights on a regular basis (the others were sanitation worker and water commissioner).”

The Oscar Lindsay House is across the street from what once was Burgess Hall or the General Mercantile Store, which was demolished in 2014 by the City of Houston. Being placed in the national register doesn’t prevent a building from being demolished, it’s largely symbolic.

Seals, who was born in 1917, graduated from Booker T. Washington High School on Yale Street, and earned a bachelor’s of science in Biology from Texas Southern University and a master’s degree in Education from Texas A&I in Kingsville. She passed in 2008 at the age of 91.

In writing about the Independence Heights Residential Historic District, Seals’ sentences are compact but convey a lot of information. Stylistically, they’re economical and lean like Hemingway:

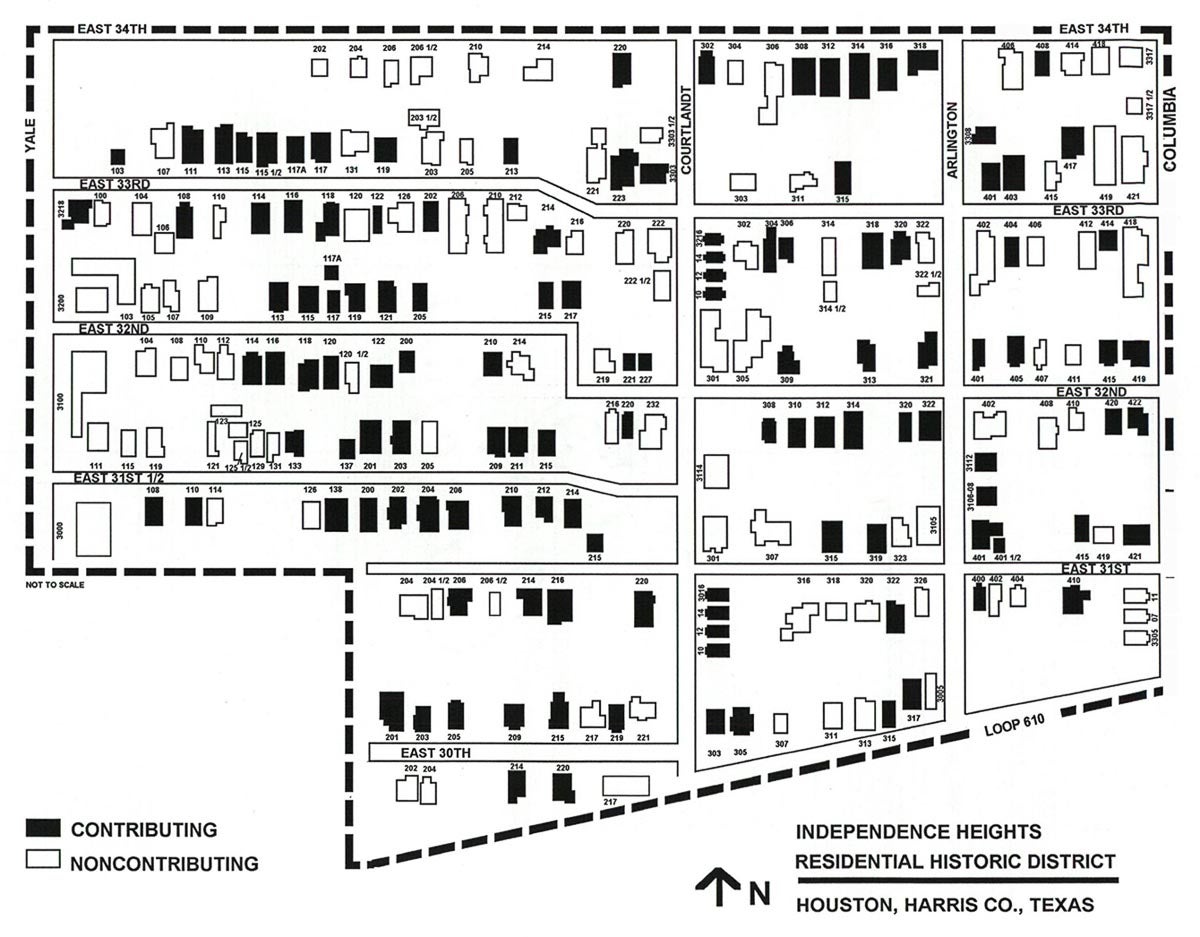

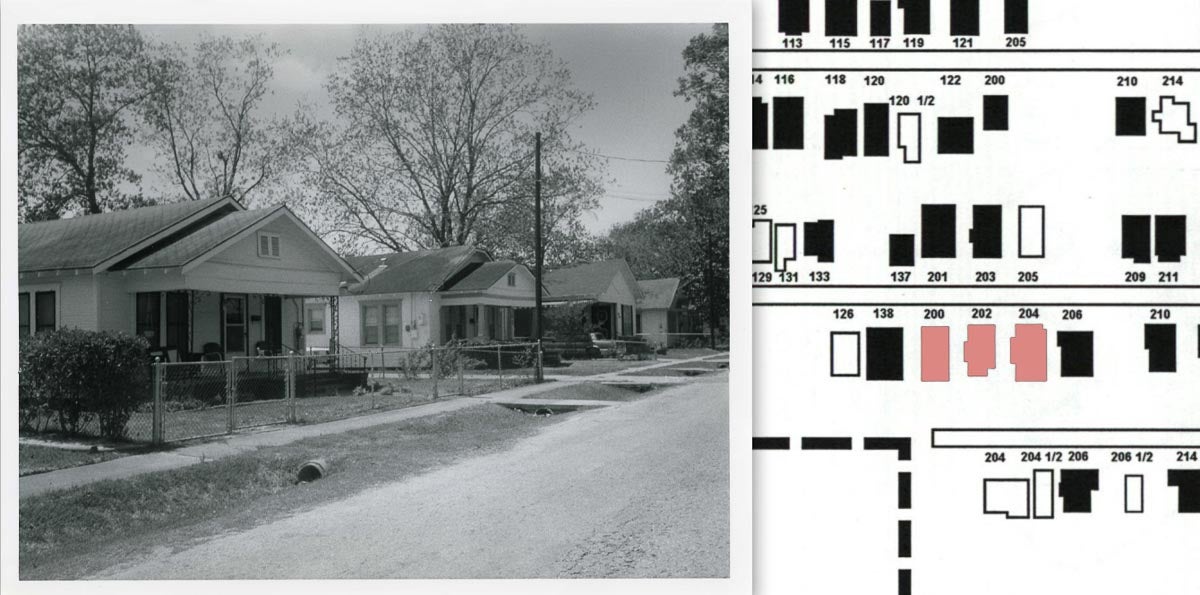

“The Independence Heights Residential Historic District covers approximately 70 acres in the southwest quadrant of the subdivision of Independence Heights. The district includes mostly 1-story dwellings ranging from vernacular shotguns to bungalows that largely date from 1908 through the 1920s. Almost all properties are of wood frame construction set on concrete or brick piers.”

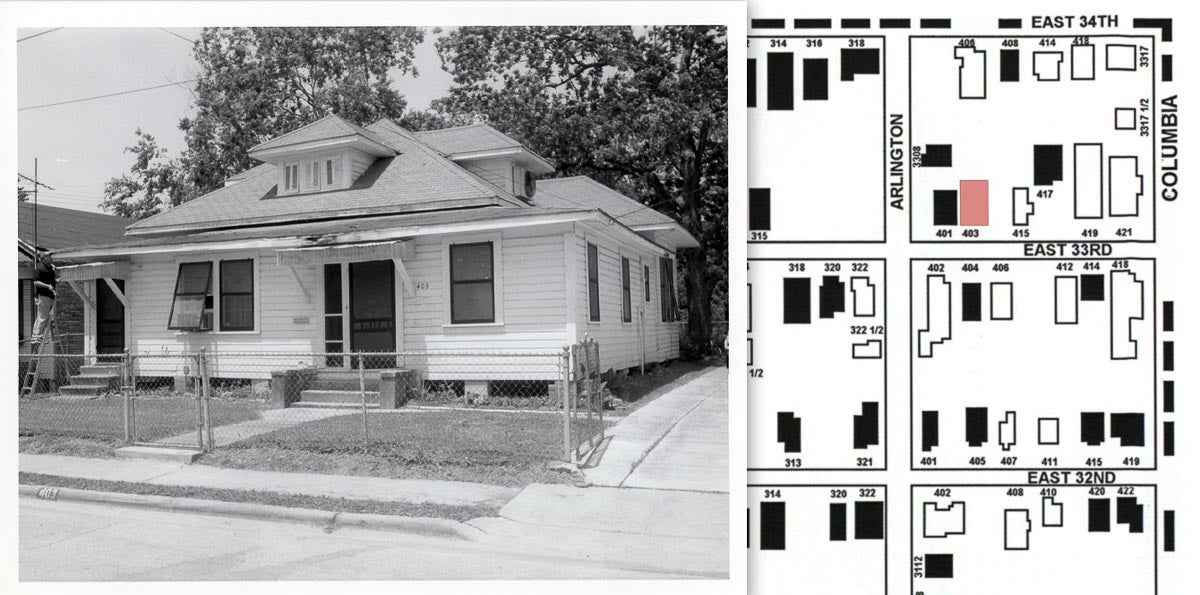

“The district includes dwellings facing streets 30th–34th running in an east-west direction and Courtlandt, Arlington, and Columbia running in a north-south direction. Many of the streets are paved with asphalt and are narrow with open drainage area[s] flanking the roadbed. A few streets are paved with concrete curbs and gutters. There are few sidewalks, generally mixing pedestrians with vehicles. Dwellings are typically on small lots and set back an inconsistent distance from the streets. Many front yards are enclosed with chain link fences that create private domestic spaces. There are few outbuildings. Landscaping is minimal except for occasional traditional plantings and some large deciduous and ornamental trees.”

“Residences in the community are largely 1-story wood frame buildings less than 1,000 square feet. Traditional house forms are common including shotguns, L-plans, modified L-plans, pyramidal-roof, and center-passage. The majority of houses, however, are simple bungalows [of] either gable-front or side-gable varieties. The houses appear to be typical dwellings probably constructed by local builders familiar with housing in other Houston neighborhoods and elsewhere.”

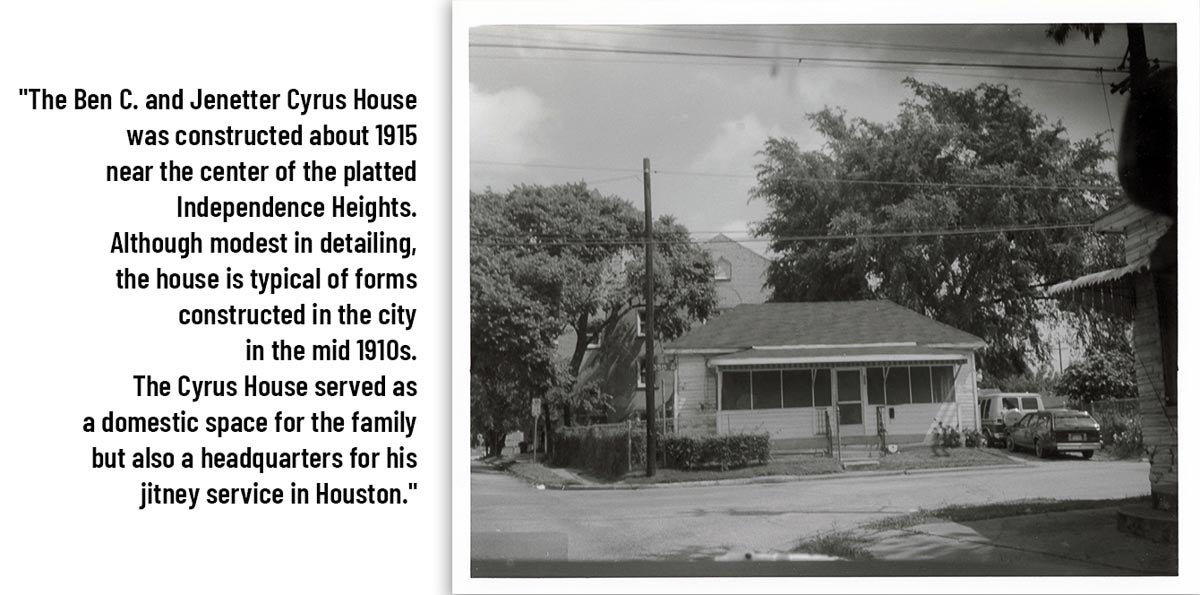

The Cyrus House

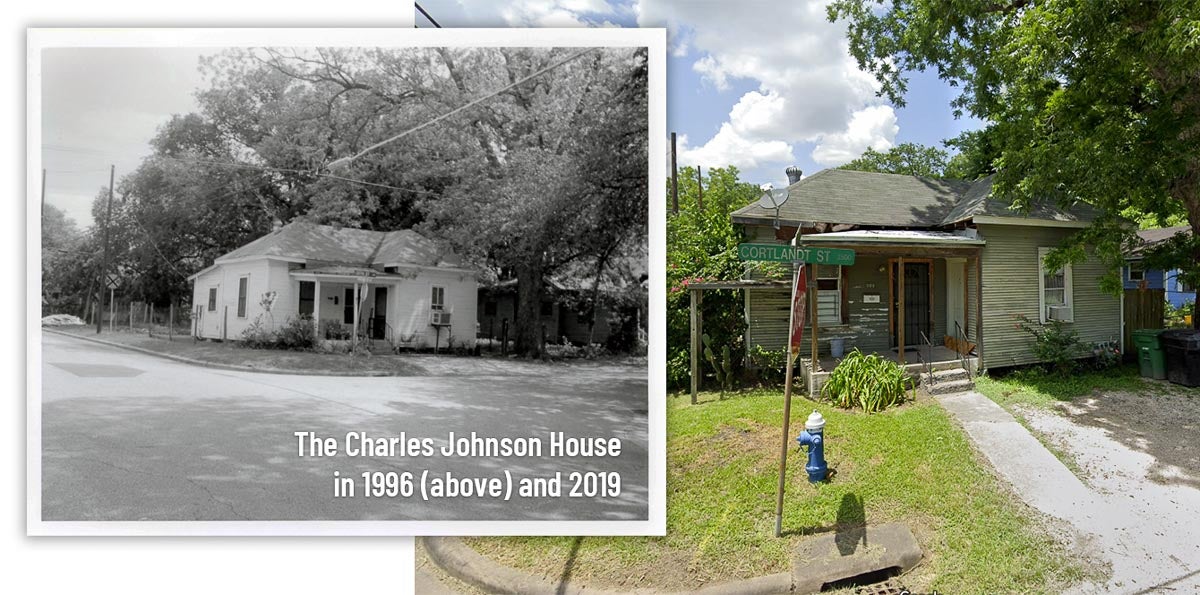

The Charles Johnson House (301 E. 35th St.)

Not all of the Independence Heights residences included in Seals' submissions to the National Register of Historic Places are still intact today. The Charles Johnson House is among those that remain.

Photo at left by Vivian Hubbard Seals / photo at right from Google Maps

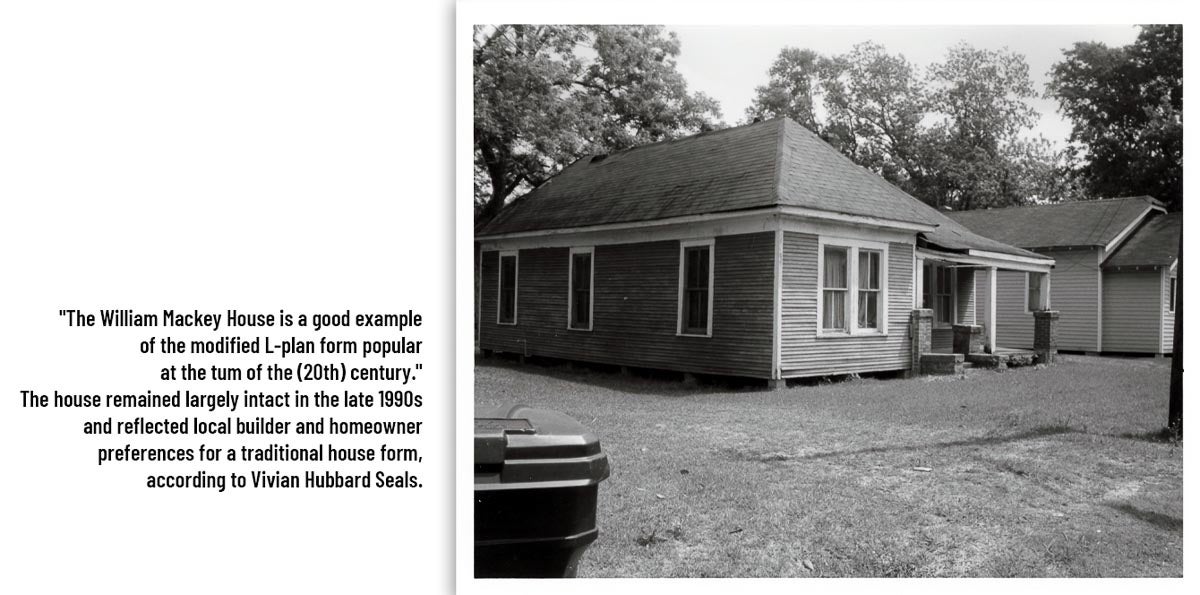

The William Mackey House (313 E. 37th St.)

“The William Mackey House dates from about 1915 and served as the home of a one of the community's most important leaders. By 1915, William Mackey became the Camp Commander of the American Woodmen Camp 272 and Tent 272. The American Woodmen Camp was one of three active fraternal organizations in Independence Heights. Fraternal organizations played a significant role in African American communities of the period by providing a social outlet as well as important functions. Such organizations often offered members insurance programs and benefits not available through private insurance companies. This service attracted many African Americans to membership. As Camp Commander, Mackey led the fraternal organization and maintained the vital link to the larger fraternal organization. No properties associated with other fraternal organizations remain in Independence Heights.

The Mackey House also served as the initial meeting place for the Unity School of Christianity. Although little is known about the school, it was one of the many religious groups that organized in the community during the early 20th century. Several extant church congregations began in the homes of local residents, but almost none of these remain.”

All of us have stories to tell

In large part, of course, the time spent trying to preserve and protect history is really about the future.

“This community is about my heritage,” says Debose. “It is about the next generation and making sure they have something to come home to, and also something to look at and be proud of, of what African American people did in a time when there was so much resistance against them.”

And she’s optimistic about where Independence Heights is headed.

Debose points to the inspiration she finds in the sixth generation of Independence Heights that is getting involved with initiatives such as “Bringing Back Main Street,” an effort to bring economic vitality back to the main corridor of the community that was once home to 40 African American-owned businesses.

Debose is also optimistic about the Texas Department of Transportation’s response to issues Independence Heights community members had with plans to expand I-45. The concessions include efforts to control flooding, including TxDOT’s agreeing to fix problematic culverts that were put in when 610 was built in 1959 that have created an ongoing bottlenecking issue at Little White Oak Bayou, which has contributed to flooding in the neighborhood, including 400 homes that flooded during Hurricane Harvey. There are also assurances that residents who lose their homes to the $7 billion highway rebuild will have options for new housing through TxDOT’s commitment of $27 million in funding to build new, affordable housing within the communities in which displaced residents currently live. TxDOT has also agreed to install community gateway projects such as murals, signage and sound walls that underscore the historical importance of Independence Heights. They also included a cultural pocket park that celebrates the community. There are also plants put in native vegetative barriers along I-45 and the installation of High-Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters and air monitors at parks and schools within 500 feet of the freeway.

For now, the project is on hold. In March, the Federal Highway Administration asked TxDOT to press pause on moving forward, and Harris County has filed a lawsuit claiming TxDOT officials ignored the county’s comments on the project.

The delay worries Debose, who sees the federal government’s deliberation and the county’s lawsuit as further threats to preservation efforts in the Independence Heights neighborhood.

“TxDOT has made $27 million available so that communities can draw down to redevelop housing (for displaced residents),” she says. (But) the longer it takes for us to access those dollars, the fewer lots there will be—and any affordable lots will be gone—and all of our historic homes will be gone.”