If you’ve been driving in Houston with any regularity this summer, let me start by saying you have my sympathies. But you may have noticed fluctuations in congestion levels on the freeways throughout the week. Take my recent experience as an anecdotal example: My younger daughter, who enjoys singing and putting on performances for the family, was enrolled in a theater camp in Rice Village the past two weeks.

Camp began each morning at 9 a.m., and somewhere in the neighborhood of 8:30, we’d make our way over there. Like so many things in Houston, this trip involved taking several freeways: First, north on 45 to that sometimes-insane stretch where the traffic streams from 45 north and south converge with the one coming from the north on 59, as everyone fights to get to 59 South. Congestion progressively worsened throughout the week, beginning on Monday, and building Tuesday and Wednesday, until reaching a crescendo on Thursday. By then the drive to theater camp had become a full-blown hellscape of confusion and frustration as we navigated a raging river of red brake lights. (This histrionic retelling is in keeping with the weeks’ theatrical theme.)

On Friday, however, everything was different. Freeway conditions were almost chill, like the calm after a violent storm. Traffic flowed at near-posted speeds; there was no honking, no foolish or aggressive driving; no one cut anyone off and no one changed lanes without first signaling. Except for that last part about the blinkers, all of this is true.

Why is that? What happened?

Here’s a theory: More and more workers who did their jobs from home throughout the pandemic (which is still ongoing, by the way, and currently surging) are returning to the office at least part time and maybe as much as four days a week. But on the fifth day, they’re working from home.

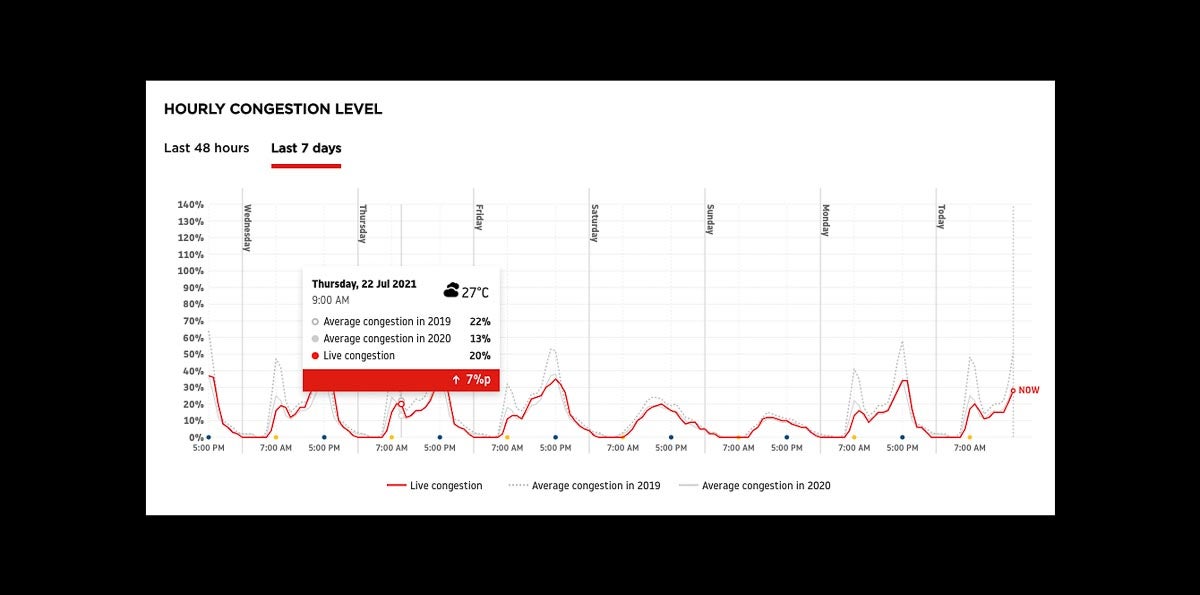

According to the TomTom Traffic Index, Houston experienced 33% less traffic in 2020 than in 2019, and the congestion level dropped 8%, from 24% in 2019 to 16% last year. (By TomTom’s math, a 30-minute trip took 24% more time — 37.2 minutes — in 2019 than it would when traffic is free flowing; in 2020, congestion added only 4.8 minutes to a 30-minute trip.) TomTom also tracks live traffic and congestion levels by the hour and those records show that last Thursday morning at 9, congestion was still slightly below pre-COVID levels at 20%, compared to 22% in 2019. Congestion in Houston last week matched closely to what it was this time last year, when traffic volume was on the rise but without the sharp rush hour peaks at 7 a.m. and 5 p.m. each weekday.

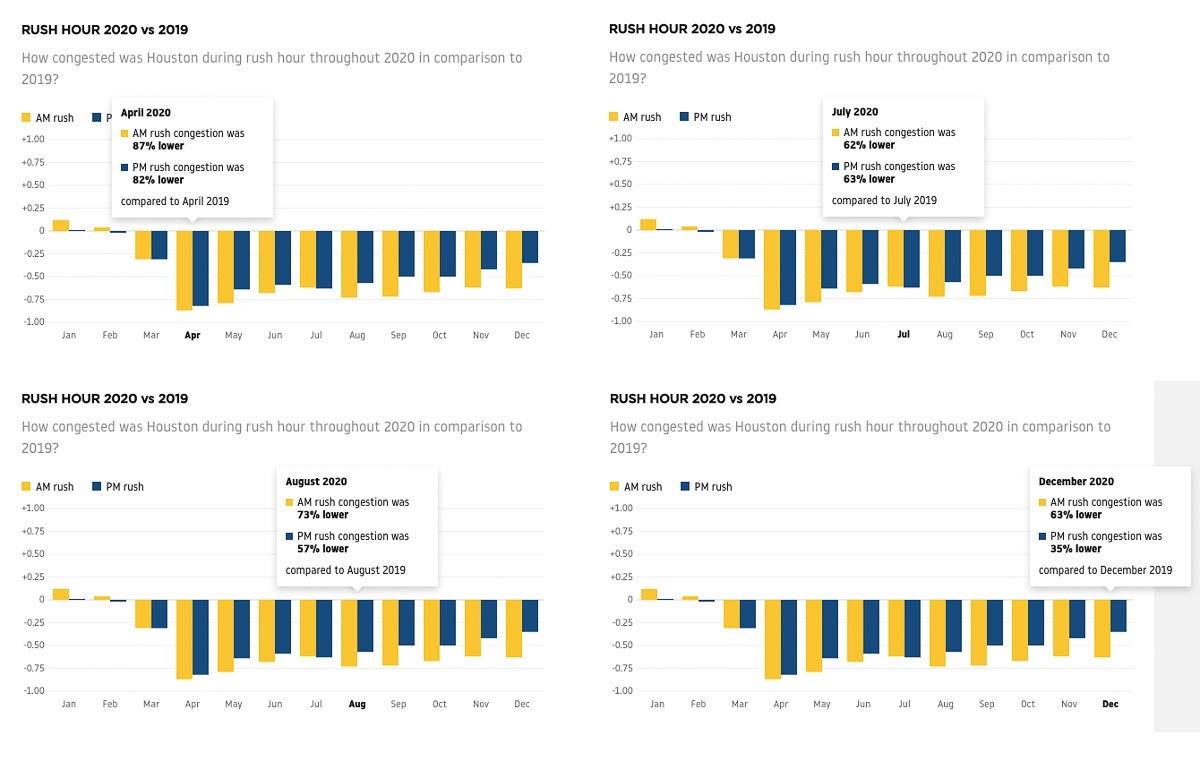

The latest Urban Mobility Report from the Texas Transportation Institute details how all the things we did to slow the pandemic — working remotely when possible, online classrooms for students, restrictions on certain businesses and staying home — flattened congestion in 2020, especially in urban areas with populations of 3 million-plus. In March, April and May of last year, it declined 60–75% in urban areas of the U.S. A better illustration of that reduction is to think about it this way: cars going 60 mph in peak times in 2020 were going 45 mph in 2019.

The decreased congestion also led to savings of time and money for drivers.

According to the semi-regular Urban Mobility Report, throughout 494 U.S. urban areas, each driver experienced an average delay of 27 hours last year, just half of the 54 hours of average delay in 2019. The cost (the cost of extra time and fuel) of congestion for each auto commuter in the nation’s urban areas was $605 — a 48% savings from $1,170 the year before. In the Houston metro area, congestion cost each commuter $1,097 — $3.8 million in total. That’s the lowest amount since 2001 and a third less than the $1,635 per driver in 2019. In all, almost 170,000 hours were lost due to traffic delays last year in the Houston area, a 36% decrease from the 2019 total of 263,000 hours. That shakes out to 49 hours per driver, which is a 27% decrease from 76 hours in 2019, the report states.

INRIX’s 2020 Global Traffic Scorecard puts the number of hours lost to delays by Houston drivers at 35, 56% less than in 2019, and the cost per driver at $523, far less than the Urban Mobility Report, which used INRIX’s data in its findings. INRIX estimates the “city cost” of Houston congestion in 2020 was $1.5 billion, which is a lot but $2.2 billion LESS than in 2019. Collisions dropped by 20% and vehicle miles traveled fell by 14%.

As we know, and is underscored in the INRIX report, the actual cost of driving extends far beyond the financial impact on individual drivers. Those costs include air and noise pollution, injuries and deaths suffered by drivers, non-drivers and passengers in crashes, as well as the property damage crashes cause.

Despite these significant changes in traffic and congestion, by the end of 2020, as the economy was gaining strength like Bruce Banner with a heart rate of 201, congestion was climbing toward pre-pandemic levels. Although levels in early 2021 remained more in line with 2009 than with those seen in 2019, the current trends indicate congestion problems will be back this year, according to the Urban Mobility Report.

“The underlying causes of traffic problems — too many car trips, too much rush hour roadwork, crashes, stalled vehicles, and weather issues — have not really receded so much as they have been eclipsed by the traffic volume decline (during the pandemic),” the authors of the report state.

Redistributing demand

Congestion and demand for trips are directly related. And in cities like Houston, that demand is met primarily by using a car. One thing the pandemic showed us is what can happen when that demand is distributed more evenly throughout the day, as opposed to two peak times during the morning and afternoon rush hours.

“If we can reduce demand, or shift travel to off-peak times, we can dramatically reduce congestion,” argues Joe Cortright at City Observatory. The trick is keeping traffic volume from exceeding the tipping point that triggers delays.

Cortright, a longtime critic of the Urban Mobility Report, recently drew attention to what he finds to be the “big, salient fact about traffic in 2020,” and one that’s shown in the Texas Transportation Institute’s data, is that traffic in American cities declined by 15–20% overall in 2020, but the drop in congestion was much more significant, down by 40–50% compared to 2019. The most important insight we have about traffic, Cortright tells us, is that it’s nonlinear, i.e., reducing travel or the number of cars on the road by a little yields substantial impacts on congestion.

In her piece, “A Little More Remote Work Could Change Rush Hour a Lot,” Emily Badger of the New York Times explored a topic of tremendous interest to researchers, planners and transit agencies, as well as the average daily commuter: How to take what we learned about the effectiveness of work flexibility during the pandemic and make it, at least to some degree, a permanent part of life in American cities, so that we avoid returning to the same old congestion problems.

Economists say something like one-third of the nation’s workers have jobs they could do from home. “Suppose many of them worked from home one day a week, or opted occasionally to read email in their bathrobes before heading in,” Badger speculated. “Overall, we’d be talking on a given day about a decline of a few percentage points in peak commuting trips — a small number, but a big deal during the most painful parts of the day.”

Will working from home survive the pandemic in Houston?

At this point it’s not clear what the future of remote work will look like in Houston. From mid-August 2020 to the end of March 2021, just over a third (33.5%) to as many as almost 42% of adults in the Houston metro area reported they lived in a household where at least one adult teleworked because of the coronavirus. That’s according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. However, since April of this year, when the vaccination was becoming more widely available, the share of Houston-area remote workers has steadily decreased.

By early July, when the state’s vaccination rate was close to 42%, only 15.6% of Household Pulse Survey respondents in Houston said they or another adult living with them were telecommuting — the lowest share among the nation’s 15 largest metros. By comparison, more than 43% of adults in the Washington, D.C., and San Francisco metros lived in a household where at least one adult was teleworking. On average, 23.5% of the workforce in the most populated metro areas were remote workers. The statewide average was 21.1%, and in the Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington area, 28.8% of adults reported living in a work-from-home household.

Now, with the spread of the Delta variant, COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations are skyrocketing in many parts of the U.S., including here in Houston, almost exclusively among the unvaccinated. Currently, 54% of the eligible population in Harris County is fully vaccinated. Will this new wave lead to businesses rethinking their plans for returning to in-person work? They may just increase the pressure on employees to get vaccinated.

If the number of remote workers continues to dwindle, are there other options for flattening congestion in Houston that don’t involve adding capacity, otherwise known as building more miles of highway?

“Many big ideas in transportation involve trying to dislodge people from the peak,” Badger wrote in the Times. “That’s the premise of congestion pricing, variable-priced toll lanes and higher peak-hour transit fares. It’s why local governments have ‘transportation demand management’ programs that try to coax commuters to take up bike-share or varied work hours.”

Unpacking some of those ideas will require its own blog post.

Cortright is a proponent of congestion pricing.

“Everyone trying to go everywhere at the same time is unsustainable and unaffordable,” Cortright has written. He maintains that roadway pricing and other strategies need to be developed and implemented so that we use “the transportation facilities we already have more efficiently before we invest in more lanes.” The money made from road pricing could be used “to ensure that the benefits and burdens of management strategies are shared equitably.”

Currently, that’s just not the case. Something many critics of attempts to build our way out of congestion say most people are unaware.

The gas tax doesn’t come close to covering the cost of building and maintaining road networks in the U.S. Research published jointly by the Frontier Groups and the U.S. PIRG Education Fund shows the amount drivers pay via gas taxes adds up to less than half of what is spent on upkeep and expansion of roads in America. The rest comes from other state and local tax revenue.

According to the 2015 report, the average U.S. household spends around $1,100 a year to “subsidize” drivers’ road use — that’s on top of what individuals already pay in gas taxes and tolls. And that’s likely an underestimate of the burden.

Americans on average saw a 33% decrease in the amount of time they spent getting to and from work each day, which in part led to more time for talking on the phone and gardening, activities we spent more time doing — 61.5% and 30.8% more time daily, respectively.

Flexible work hours, compressed work weeks, telework, as well as pricing strategies, along with more policies, programs, projects, flexibility, options, and understanding, are among the approaches recommended by the authors of the Urban Mobility Report for fighting congestion, who seem resigned to the fact that 2020’s huge drop in congestion won’t be the new normal. They could be wrong.