Vaccine hesitancy, which comes in many forms, is a serious roadblock to the 80-90% vaccination rate needed to achieve a measure of control over the virus’ latest variant. What is increasingly a more likely outcome is that the coronavirus becomes endemic, a vicious viral partner that, along with the common cold and the flu, stays with us perhaps forever.

Just when we thought we were on our way out, we were pulled back in. The Atlantic’s science writer Ed Yong put it: “The U.S. is once again looping through the pandemic spiral. Arguably, it never stopped.”

While the U.S. was never in the clear, cases and hospitalizations had dropped significantly this summer. A study by the Yale School of Public Health concluded that the vaccination effort through July had saved 279,000 lives and prevented 1.25 million hospitalizations.

Since January of this year, after vaccines first became available, the US Census Household Pulse Survey began asking about intentions to get vaccinated. As of Aug. 2, the most recent survey sample available, about 16% of Americans were still hesitant to get vaccinated, including 20% of Texans. Those figures are down by about half since January.

Meanwhile, vaccination rates in Texas (45% of the whole population) and Harris County (47%) lag the country (49%) as well. (Higher figures are often reported, such as the country’s 70% of all adults being vaccinated as of Aug. 3, but to achieve anything close to herd immunity, the rate must account for the whole population.)

While vaccine uptake has increased in the past month, this hesitancy persists, and could mean that millions of adults (and their children) may never be vaccinated. Driving this hesitation is a growing suspicion about the vaccines, which are on the cusp of full FDA approval.

The most common reasons cited in the Pulse survey are concerns about side effects (53%), lack of trust in the vaccine (50%) and lack of trust in the US government (43%). In the Houston area in particular, concerns about side effects are the by far the most significant reason for hesitating to get the shot, with 61% of hesitating people saying that’s was reason in the July survey period, up from 27% when the survey began asking the question. By comparison, the other top reasons in Houston in July were “don’t trust the vaccine” with 34% and “don’t know if it will work” with 24%.)

A separate survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found similar conclusions—unvaccinated adults were more likely to say that the vaccine posed higher risks than the virus and that the vaccine is not effective.

On the one hand, it could be that the variants themselves are hardening the stance of those who did not believe the vaccine would be helpful—they can now point to the news and say “Look, vaccines don’t work!” (In reality, “breakthrough infections” do make headlines, but they are extremely rare. Out of 166 million vaccinated people in the US, about 8,000 have experienced a severe breakthrough infection. Unvaccinated people, on the other hand, make up the vast majority of new cases and almost all hospitalizations and deaths in recent weeks.)

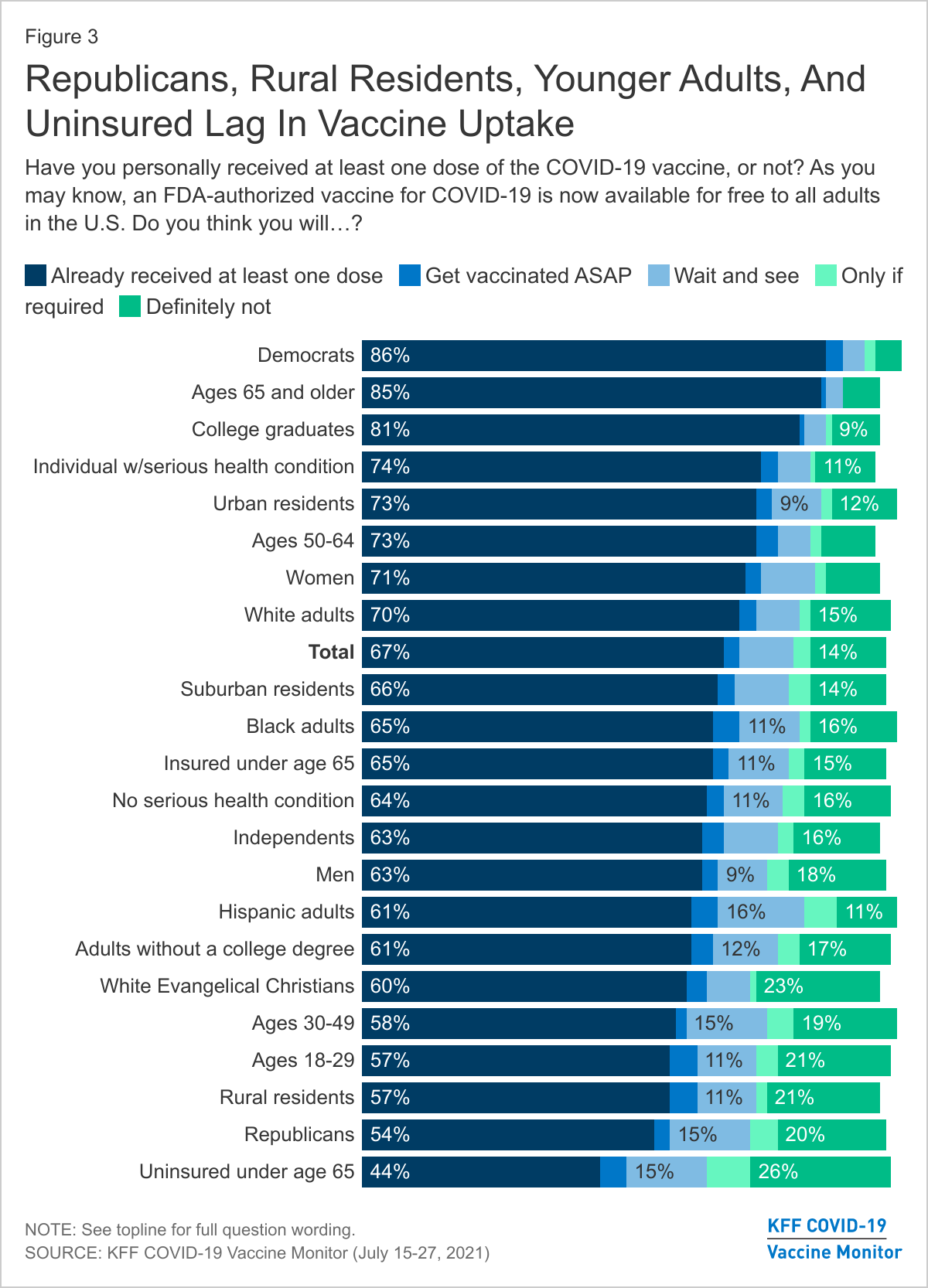

The Pulse survey shows an an educational divide, with those with only a high school diploma or less more likely to report hesitancy. Those without health insurance coverage are also more hesitant, as are adults aged 25-39. The Kaiser Family Foundation poll also found gaps between urban and rural residents, not to mention a glaring partisan divide.

In Harris County, vaccination rates are highest in the most affluent ZIP codes on the west side of Houston— unsurprisingly, as this blog has pointed out, that’s where many of the city’s first vaccination hubs were established. Education level seems to be one of the biggest predictors of vaccination. In ZIP codes with a majority of adults having at least some college, 56% are vaccinated. In ZIP codes where the majority does not have any college education, the average is 37%. That suggests socioeconomic factors, not ideology, are slowing down vaccine progress—factors such as having jobs that are less flexible, and having less access to health care and child care. These ZIP codes also have higher shares of Hispanic and Black residents.

One of the most densely populated ZIP codes, 77081, with over 30,000 residents, has one of the lowest vaccination rates in the county, 30%. That’s concerning, because this area is also home to a higher percentage of overcrowded housing, which, as we documented in the State of Housing report, means greater opportunities for transmission of the virus. Having vaccine clinics located nearby is clearly not the issue—77081 is located near affluent areas, such as adjacent ZIP code of 77401 (Bellaire), which has a 64% vaccination rate—also suggesting other barriers exist.

Achieving higher vaccination rates is still possible, and it may not be just about fighting misinformation and overcoming ideology. More practical steps could be the answer.

As Bryce Covert wrote for the New York Times: “Those who are unvaccinated are also likely to work in essential jobs like agriculture and manufacturing that don’t allow them to step away from work. They work long hours and may prioritize time with their families or communities when they finally get a break. People who have multiple jobs may find it impossible to schedule a shot in between all of their shifts.”

To get the next 10-20% of people vaccinated, officials need to get creative, and a $25 incentive is probably not going to cut it. Apartment complexes, workplaces, churches and community centers could host vaccination drives—which can improve access as well as build trust. More workplaces can offer paid time off, provide transportation and assist with child care to help working class parents get access to vaccines. (Find where you can get vaccinated at vaccines.gov.) Meanwhile, full FDA clearance will also go a long way to allaying fears, which will close some gaps among the hesitant.

The ideal outcome is that enough people in each city, state and nation get vaccinated so that anyone who cannot or will not get the shot are protected by the vast majority who do. But as long as the coronavirus has enough vulnerable people it can use to multiply and mutate into new strains—either here or abroad—then the unvaccinated will dictate the pandemic's next move.