Each year for the past four decades, Stephen Klineberg has written a new chapter in the story of Houston through the Kinder Houston Area Survey. It’s a gripping tale that includes economic and natural disasters, as well as economic windfalls and incredible displays of resiliency and an inspiring degree of optimism about the future and a populace’s willingness to open their minds and hearts to others. The ongoing saga of the city and surrounding Harris County is also a living, dynamic document that changes as residents’ economic outlooks, experiences and beliefs have evolved.

In many ways, the Houston and Harris County of 1982 scarcely resemble themselves today. The Houston Area Survey, which Klineberg says “fell into my lap back in 1982,” was launched as a one-time class project on Houston’s booming economy to teach Rice University sociology majors research methods.

“So, we did a one-time survey to measure, ‘how are people experiencing this tremendous wealth? There were growing concerns about pollution, crime and traffic. What kind of city are we building with all this affluence?’”

Two months after the project was completed, the oil boom collapsed. What followed was a devastating recession that lasted throughout the ’80s and almost broke the city.

But Houston didn’t break. Instead, the city and surrounding region began a yearslong transformation, from an economy dominated by one industry and one race to one that has diversified economically and demographically, becoming one of the most diverse places in America.

Stephen Klineberg with student researchers in 1982, the first year the Houston Area Survey was conducted.

Photo courtesy of Fondren Library’s Woodson Research Center / Special Collections

When asked to name some of the most significant findings from the past 40 years of Houston Area Surveys, Klineberg points to the increased awareness among Houstonians that, “the strategies we need to put into place today to position Houston for prosperity are different from the strategies that worked so well for the city in the 20th century.

“We Houstonians proclaimed ourselves to be the epitome of what Americans can achieve when left unfettered by zoning, government regulations and taxation,” Klineberg says. “We are now prepared to say the pro-growth strategies are different today. If Houston is going to make it, it needs to become a more resilient city.”

The need to build resilience

Historically, says Klineberg, Houston has been “a famously anti-government, free-enterprise city.” During much of the 20th century, the city embraced and enabled the risk-taking entrepreneur, and that attracted a lot of businesses (large and small) and big ideas to the region. Its fiercely independent, all-or-nothing spirit has been romanticized and woven into the fabric of the region’s history. The space program ... the world’s first domed stadium ... the first artificial heart transplant. It’s that entrepreneurial spirit that also has been a magnet for migration for more than 40 years.

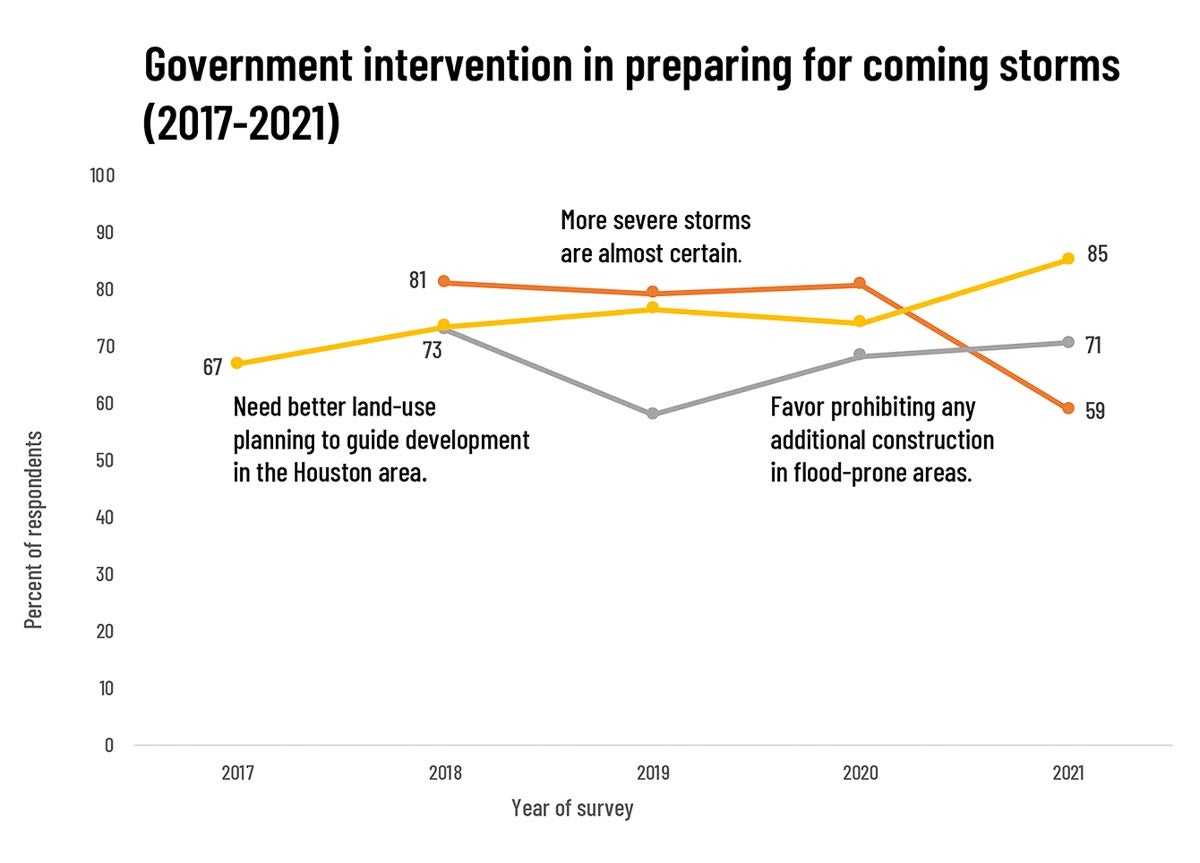

Residents support more stringent controls on development to mitigate future storms, to enhance the area’s quality-of-life attributes, and to develop more walkable urban neighborhoods.

It’s widely known that Houston doesn’t have zoning. For many outsiders, it’s a characteristic that has come to define the city as much as its legendary sprawl. But, just as there are densely populated areas of the city, there are ways that land use is regulated. (Zoning and planning often are conflated.)

As market urbanists point out, the city’s liberal approach to regulations has led to more density, mixed-use development and housing that’s affordable to many, especially compared to many U.S. cities where zoning has been an obstacle. Released last month, the Kinder Institute’s “Re-Taking Stock Report” showed housing development inside Loop 610, which accounts for just 15% of the city’s total land area, surpassed the total annual housing production of other major U.S. cities in recent years. But the region’s problems with flooding extend far outside of the dense urban core to areas where there’s been substantial development—none of it dense.

Sociologist Kevin T. Smiley and ecologist Christopher R. Hakkenberg found that almost 187,000 football fields of impervious surfaces such as concrete were added in the Houston metro area from 1997 to 2016.

“This environmental change means not only hotter urban temperatures and the loss of precious ecological habitat, but also rising flood risks as impervious surfaces concentrate flood waters in vulnerable areas rather than disperse them the way natural surfaces like forests, parks or farmlands tend to do,” they noted.

In the past six years, the Houston metro has seen several major 500-year rain events, like the Memorial Day (2015) and Tax Day (2016) floods and Hurricane Harvey (2017), made even worse by the lack of planning and regulation of the past. The region is being forced to retroactively build resilience into the built environment.

“Houston is a prime example of a city that has failed to see the risk they are creating through their development and expansion. Houston’s population has grown exponentially in the last three decades, and the city has shirked proposals for new building codes and flood-control projects,” Kevin Fitzpatrick and Matthew Spialek wrote in their book, “Hurricane Harvey’s Aftermath: Place, Race and Inequality in Disaster Recovery.”

Area residents overall are more prepared than in previous years to embrace the new realities.

Three times in the past 75 years—in 1947, 1962 and 1993—Houston voters rejected zoning referendums. But when asked if they favor or oppose citywide control and planning over the uses of the land in different areas, 61.3% and 50.6% of survey respondents in 1990 and 1993, respectively, were in favor. The question was asked in the surveys conducted in 1994, 1996, 1999 and 2008, and each year, more respondents were in favor than opposed. From 2017 to 2021, the survey has shown increasing support for government intervention in preparing for coming storms. In 2017, 67% of survey participants said there’s a need for better land-use planning to guide development. This year, 85% agreed with that statement.

Action by city leaders and county voters back up the shifting attitudes found in the surveys. In April 2018, seven months after Hurricane Harvey, the Houston City Council voted to require all new developments in the area’s floodplains to be built two feet above the projected water level in a 500-year storm. And a year after Harvey, Harris County voters overwhelmingly approved a property tax increase to pay for $2.5 billion in flood infrastructure designed to help protect the area during future storms.

“Houston’s time-honored resistance to government interference in private property decisions clearly seems to be giving way to a more pragmatic assessment of what this city needs to do as it seeks to position itself for prosperity in the face of climate change,” Klineberg and Bozick wrote in the latest survey report.

The need to reduce inequalities

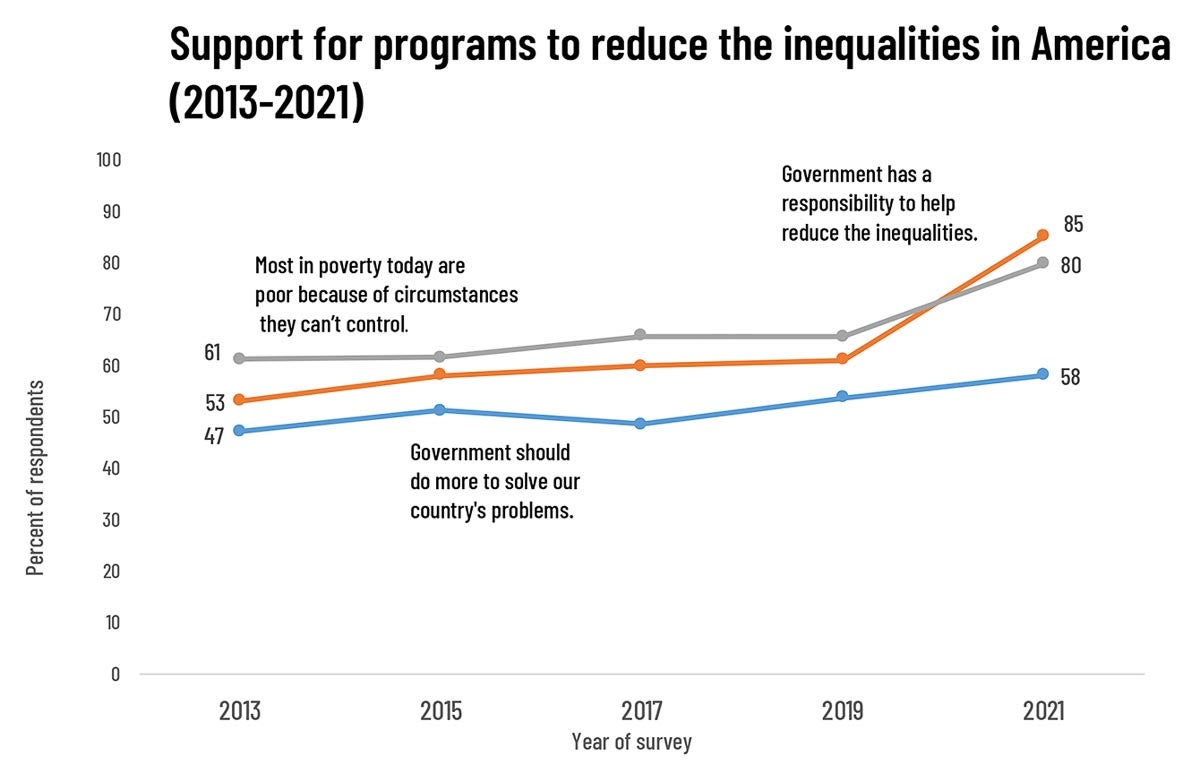

Not only are Houstonians recognizing the critical role of government in building resiliency to the effects of climate change, according to the Houston Area Surveys, they also increasingly are acknowledging the need for government intervention to strengthen the safety net and expand opportunity.

Since 2013, support for programs to reduce the inequalities America — including those related to education, economic well-being and health care — has gone up among Harris County residents. Today, 85% say that the government has a responsibility to help reduce the inequalities between rich and poor in America. That’s compared to 53% who agreed in 2013.

Klineberg attributes these shifting outlooks as well as others that reflect the continued and growing embrace of diversity, especially among white residents, not by gender or education, but by year of birth.

Houstonians are calling for more government efforts to reduce the income and opportunity gaps.

When asked about the Dream Act (“allowing the children of undocumented immigrants to become U.S. citizens if they have graduated from college or served in the military”), the already high support among white residents in 2013—76%—rose to 88% in the 2021 survey. And close to 75% of white survey participants favor granting undocumented immigrants a path to citizenship.

Since the oil-boom collapse in 1982, Klineberg writes in his book “Prophetic City: Houston on the Cusp of a Changing America,” “immigration from abroad, (and) new births, primarily the children of earlier immigrants and of U.S.-born Hispanics, Asians and African Americans,” have accounted for all of the net growth in Houston’s population.

“We are in the midst of this fundamental transformation, from a city totally dominated and controlled by white men into the most ethnically diverse city in the country,” Klineberg says. “And it’s happening right before our eyes.”

Between 2010 and 2019, the populations of Black and Hispanic children in Harris County grew by 12,000 and 75,000, respectively. Overall, 70% of Harris County residents under the age of 20 are African American or Hispanic.

“The two groups overwhelmingly are most likely to be living in poverty,” Klineberg points out. “That’s going to be our future unless more investments are made.”

This year’s survey shows 31% of Black households in Harris County make less than $37,500 a year, while 44% of Hispanic households make less than that amount. Overall, one in four Harris County residents said they didn’t have health insurance, and more than one-third of survey respondents said that if confronted with an emergency that cost $400, they wouldn’t be able to cover it. Such a lack of basic resources was much worse for Hispanic and Black residents compared to Asian American and white residents. Forty-four percent of Black residents and 45% of Hispanics said they didn’t have $400 on hand for an emergency. More than 40% of Hispanic respondents said their family had no health insurance, while the same was true for 22% of Black participants.

In addition to hardships like these, more than one-fourth of residents said they had trouble paying for housing.

These and other disparities have shown up in previous editions of the survey, but they worsened during the yearlong COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected Hispanics and African Americans—financially and in terms of infections and deaths. As the gaps in wealth and access to health care persist, they’re only likely to grow.

“The underclass is growing faster. There is an inability to respond to the daily disasters of being poor," Judson Robinson III, president of the Houston Area Urban League, told Klineberg in “Prophetic City.” “People are overwhelmed by societal factors. And then on top of everything, Houston has to deal with worsening floods and storms. So if you lost your car in a flood, chances are you lost your job, too, because you had no way to get to work.”

Like flooding, being poor is a reality for many in the Houston area—one they can’t control. And, according to the Houston Area Survey, that’s a realization for more and more residents. This year’s Houston Area Survey revealed a large jump in the share of respondents who agree that most of the people experiencing poverty in the U.S. are poor because of circumstances they can’t control, not because they don’t work hard — from 66% two years ago to 80% in 2021. In 2013, just 61% said being poor was something people couldn’t control.

This year’s survey shows a “broader awareness that people are poor in this country through no fault of their own, and that government has a critical role to play in economic justice," Klineberg explains.

During the booming years before the 1980s, there were plenty of good blue-collar jobs in Houston, and you didn’t need a college degree to earn a good living.

“Suddenly, now, it’s a new world where blue-collar jobs have disappeared and there are growing inequalities across the board predicated, above all else, on access to quality education.”

One intervention Houstonians support is expanding access to early childhood education, which has been shown to greatly improve a child’s life chances.

The survey participants increasingly assert the urgent need for major new investments to achieve sustained improvements in the public schools, from cradle to career, from birth through college.

Children who complete pre-K, according to research from the Houston Education Research Consortium, are better prepared for kindergarten, which triggers a chain reaction of success in the years to come. Compared to students who don’t go to pre-K, those who attend do better in later grades and are less likely to repeat a grade; they also complete more years of education and earn more money as adults. All of those benefits benefit the Houston area as well.

Some cities and states fund free preschool, and there are plans being proposed that would make free, high-quality preschool available for all 3- and 4-year-olds. That would be a tremendous benefit to students and their families, but, Klineberg states adamantly, more investment in education is needed. The Houston area’s future depends on it.

“Texas and Houston are at the bottom still in their spending on education,” he says. “We are way behind both San Antonio and Dallas in the percentage of kids from poor families who have access to quality preschool. And that’s a great problem for Houston.”

As previous surveys have shown, residents acknowledge the urgent need for major investments in Houston’s public schools. In 2020, 70% of respondents said they were in favor of increasing local taxes to pay for universal preschool for all children in Houston.

“We are understanding these issues better than we did before,” Klineberg says. “But we’re not doing much about it as of yet.”

The most pressing question remains unanswered

That’s why, after 40 years and counting of studying Houston, he says, “the jury is out“ on the future of the city.

What’s not yet clear, according to Klineberg, is whether Houstonians are prepared to raise taxes and use government programs to make sure that not only their children get the education and support they need to be successful, but that all children—and the city as a whole—have the resources they need to make it.

“We’re great believers in philanthropy. We’re great believers in volunteerism. We don’t like government. But that’s beginning to change. Houston really is in a different place today. Whether we can translate that difference into effective, meaningful action is really the question mark for the future.”