What’s the biggest problem facing people in the Houston area today?

If asked that question in the past month and a half, it seems like easy money to bet every response would involve the economy or health.

But back in late January and early March of this year, when interviews for the 2020 Kinder Houston Area Survey were conducted, congestion on the city’s streets and freeways was the most-common concern. (It was the top response in the previous three years as well.)

Among respondents, 30% cited traffic while only 13% pointed to the economy as the biggest problem. And for good reason. Unemployment was at a 50-year low and the three major stock market indexes were near record highs.

Then came COVID-19.

Eery similarities between 2020 and 1982

Interviews for the 39th annual survey began Jan. 28 and concluded March 12, the day after the World Health Organization declared the pandemic. In some ways, it was the calm before the storm, though the markets began their dramatic decline Feb 19. Because of the timing, parts of the survey show the “old normal” preserved in amber.

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

So far, there have been more than 8,800 confirmed cases in Houston and Harris County, and 193 deaths.

Before the pandemic, the outlook on job opportunities was overwhelmingly positive, with 69% describing them as “excellent” or “good.” Other than 2015, which was also 69%, that’s the most optimistic view of employment since 1982 when 71% of respondents said job opportunities were excellent or good.

In the 1970s and early ‘80s, Houston was the “Golden Buckle of the Sun Belt” and the epitome of “free enterprise” America, said Stephen L. Klineberg, founding director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research. During that time, 82% of primary-sector jobs were tied to the oil business.

Up to then, the city had been riding an unprecedented high of economic expansion. Houston, one observer wrote, was “a phenomenon; an explosive, churning, roaring urban juggernaut that’s shattering tradition as it expands outward and upward with an energy that stuns even its residents.”

Klineberg’s 1982 survey — the first conducted — was completed two months before an oil bust that resulted in the eventual loss of 100,000 jobs in the Houston region.

“Booms and busts are an integral part of the cyclical nature of the oil business, but every once in a while, there are some really big ones that change the nature of the oil patch itself,” Klineberg said. “One may well be happening today: the excess supply and collapsing demand are much like they were in May of 1982 when the world that Houston inhabited changed forever.”

When the next survey came out in 1983, the positive outlook on employment had been cut in half, plunging to 35%. It would reach its lowest level — 11% — in 1987. By that time, Houston had lost one of every seven jobs it had in 1982 and economic fears were the greatest problem facing the region, according to 72% of respondents to the 1987 survey.

Portions of the 2020 Kinder Houston Area Survey are life as we knew it preserved in amber.

Andy Olin / Kinder Institute

City hit with an economic double whammy

Today, Houston looks more like an overmatched fighter facing a brutal one-two punch of economic hardship: One of those “really big” oil busts and a 100-year pandemic that effectively shut down the nation’s economy.

For March, the unemployment rate in the Houston metropolitan area was 5.1%, one of the highest among the largest metros in the country. And all signs point to those numbers rising dramatically when state and local unemployment figures are released May 22.

Nationally, the economy has lost more than 20 million jobs and in April the unemployment rate jumped to 14.7%; however, the actual rate could be as high as 20%.

Last week, the Federal Reserve chair, Jerome H. Powell, said the United States was experiencing an economic fallout “without modern precedent.”

An estimated 350,000 jobs have been lost in Houston since March when many businesses across all sectors were forced to close to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, said local economist Patrick Jankowski. Statewide, the sectors impacted the most were hotels, restaurants and bars; retail trade; and health care.

Approximately one-third of Houston’s economy is tied directly to oil and gas, and one in 10 jobs in the region are in the energy industry, according to Jankowski, the Greater Houston Partnership’s senior vice president of research.

“In the end, Houston may be hit hardest in the long-term,” Klineberg said. “Not suffering so much from the pandemic but suffering from the economic fallout following it (especially collapse in oil prices).”

The already vulnerable must now contend with new economic decline

Early in the pandemic, it appeared COVID-19 would be a disease that didn’t discriminate. Initially, it was affecting the affluent and relatively well-off who were traveling for business or vacation. There were clusters of disease on cruise ships that acted like floating Petri dishes. According to a Los Angeles Times report, residents in many developing countries called it “a rich man’s disease.”

Per the Times’ story, the governor of Mexico’s Puebla state said: “If you’re rich, you’re at risk. … The poor, we’re immune.”

However, it quickly became apparent that already vulnerable populations would pay a disproportionate price. As cities, counties and states began issuing stay-at-home orders, those in jobs that could be done from home, which tend to be higher-paying, could more easily control their risk. Meanwhile, many of those working essential — and often low-paying — jobs like grocery store employees, delivery drivers and personal care assistants were exposed to a much greater risk of infection.

It’s the same in the Houston area, where many of the residents hardest hit by COVID-19-related job losses were dealing with economic precariousness before the downturn. A dashboard created by the Kinder Institute’s Houston Community Data Connections shows the neighborhoods in Harris County impacted the most are home to large numbers of low-income renters, the working poor and single-parent households.

“The burden has fallen most heavily on those least able to bear it,” Powell said in his address. “Among people who were working in February, almost 40% of those in households making less than $40,000 a year had lost a job in March.”

Analysis of data from the Gulf Coast COVID-19 Community Impact Survey by the Kinder Institute’s Houston Education Research Consortium reveals that, overall, 35% of working adults have experienced negative employment impacts because of COVID-19. But that number spikes to almost 80% for workers in the hospitality and entertainment and recreation industries. And in most industries, workers earning less than $50,000 were two to four times more likely to report negative job impacts than residents earning $100,000 or more.

“We learned from Harvey that disasters do discriminate,” Klineberg told KHOU. His comments were for a story about residents of zip codes with the highest concentration of COVID-19 cases earning less and being more likely to be Hispanic or black than other areas.

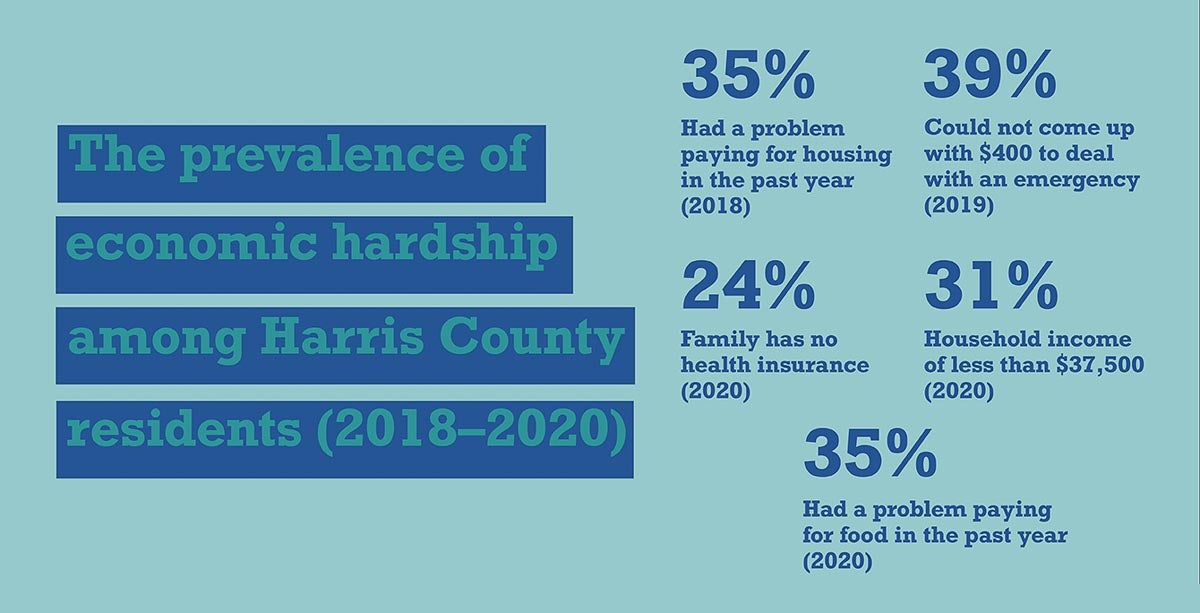

As the 2020 Kinder survey shows, these disparities existed long before the COVID-19 pandemic:

“The coronavirus has laid bare the dimensions of the city’s deepening inequalities in access to health care and economic opportunity, and it has underscored the dire consequences for Houston’s minority communities.”

Overall, almost 40% of Harris County residents are unable to cover an emergency expense of $400. Nearly one-quarter of families are uninsured. Over 30% of Harris County households have incomes of less than $37,500. Paying for groceries to feed their family was a problem for 35% of residents in the past year. And 35% struggled to pay for housing.

Federal poverty guidelines for 2020 set the income threshold for a family of four at $26,200.

When these groups of economically vulnerable residents are broken down by ethnicity, the sizable racial disparities can be seen:

► 36% of U.S.-born Hispanic households make less than $37,500 a year

► 42% of African American households earn that much annually

► And more than half of Hispanic immigrant households make less than that in a year.

In contrast, 83% of white households made more than $37,500, as did 82% of Asian households.

When asked how they would cover the cost of a $400 emergency expense, more than 60% of Hispanic immigrant households said they couldn’t. Close to half of U.S.-born Hispanic households and 56% of African American families wouldn’t be able to afford the expense. That’s compared to 16% and 30% of white and Asian households, respectively, that wouldn’t have the money in an emergency.

These inequalities will play a large part in the city’s future

According to the survey: “During the past three decades, virtually all the net growth of this city has been thanks to the influx of Hispanics, Asians, and African Americans. This traditionally biracial southern city has transformed into, by some measures, the single-most ethnically and culturally diverse major metropolitan region in the country. And the differences by age are striking: Anglo Houstonians are disproportionately older. The “aging of America” is turning out to be as much a division along ethnic and socioeconomic lines as it is along generational lines.”

The growing diversity of the population in Harris County will continue in the years to come. Of those under the age of 20 today, more than 70% are African American or Hispanic.

As COVID-19 has spread around the world, it has taken a tremendous human and economic toll, and in many ways, that toll has been greater for communities of color. The outbreak has shown us that no one is safe until everyone is safe. The same is true for Houston and its viability in the long term.

If these preexisting racial and ethnic inequalities continue, the impact on the future of the entire metro area will be enormous and potentially devastating.