By late March, as many as 3 billion people worldwide were told to stay home to combat the coronavirus pandemic. What followed during the economic shutdown and sweeping stay-at-home orders has been covered here and elsewhere: global emissions were reduced and air quality improved as planes were grounded and traffic volume fell dramatically.

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

Between March 15 and June 15, greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. fell 18% compared to 2019 levels during the same time, and traffic activity dipped more than a billion miles a day, from 9 to 7.9 billion. With less-congested roads and highways, however, average speeds and the associated dangers increased.

In cities like New York, Sao Paulo, Seattle, London and Singapore, driving, walking and public transit use all decreased greatly beginning in January and February, with the largest decrease seen in public transit. From mid-March till early June, Harris County saw a dramatic drop — as much as 66% — in traffic levels.

And while driving levels have rebounded significantly, even returning to pre-pandemic levels in many parts of the U.S. — especially rural and suburban areas — use of public transit remains very low.

“The trend we’re seeing is not pleasant,” said Laura Schewel, CEO of Streetlight Data, which developed a VMT Monitor that provides daily totals of vehicle miles traveled in each county in the U.S.

In an interview with Government Technology, Schewel said data from the monitor indicates transit isn’t bouncing back in the same way as driving — not even close.

“What we also think we’re seeing is a mode-shift,” Schewel said. “And that is alarming for what it means for the future of cities, for the future of congestion, things like that.”

Nationwide, transit ridership fell 9.9% in the first quarter of 2020, compared to 2019, according to the American Public Transit Association (APTA). It dropped 40.7% in March, after being up 6.2% and 7.9% overall in the first two months of the year.

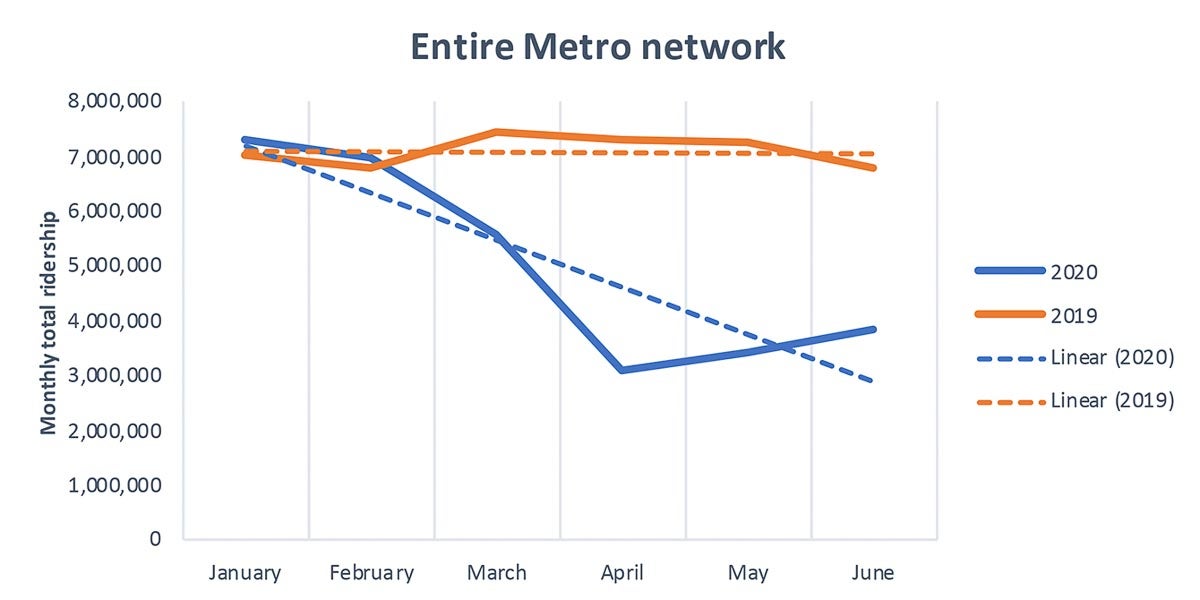

In the Houston area, Metro’s total ridership fell 6.7% in the first quarter, and 25% in March, compared to 2019. In the second quarter, ridership was down 51% over 2019. And from the first to the second quarter of 2020, total ridership declined 48%.

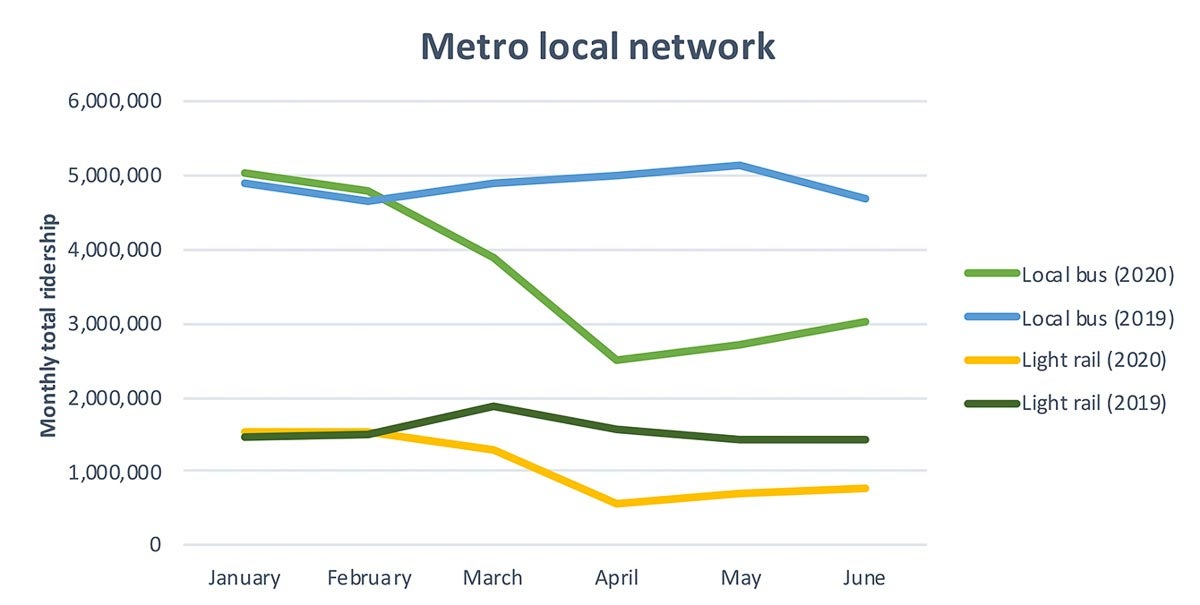

Compared to first-quarter totals in 2019, local bus and light rail ridership decreased by 6.4% in the first three months of 2020. It was down 47% in the second quarter. So far, ridership for Metro’s local network has dropped 26.6% in the first six months of the year, compared to last. Local bus ridership is down 25% and light rail ridership has fallen 32%.

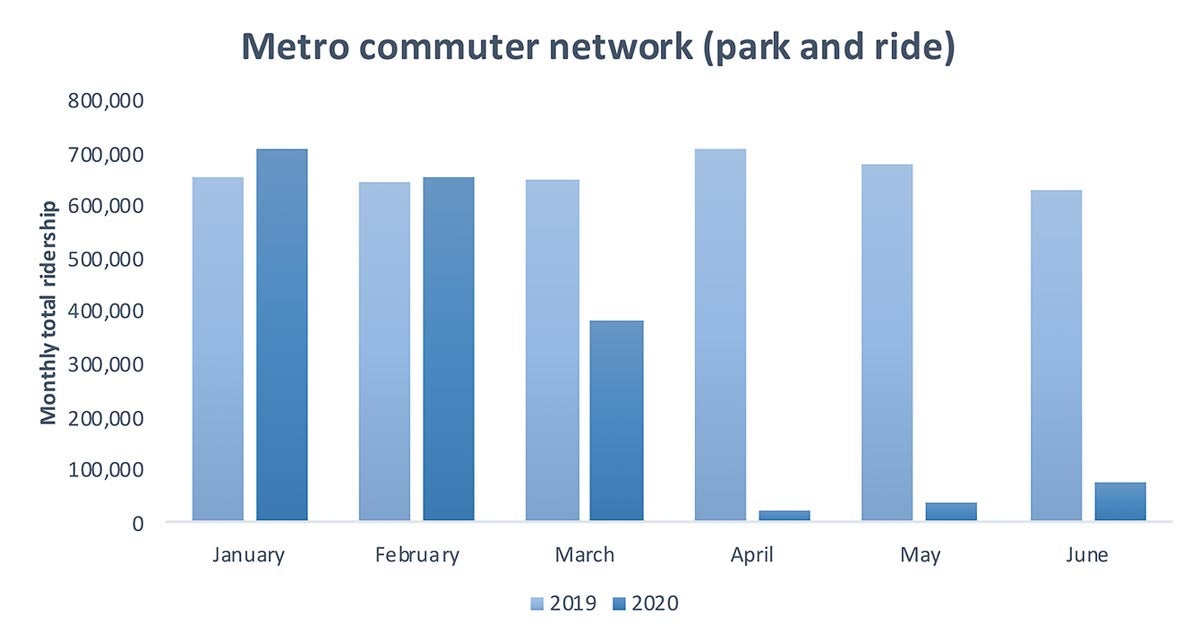

Ridership on the transit agency’s commuter network — its park and ride service — is half what it was in 2019, falling 52.5% in the first two quarters of 2020.

Metro has reduced and modified services in response to the coronavirus pandemic, not only because of the impact on ridership from people staying home and working from home, but also to fight the spread of COVID-19.

“For Park and Ride routes, Metro is carrying only 12 percent of July 2019’s average daily ridership but is operating the equivalent of 35 percent of July 2019’s service levels,” Metro’s Monica Russo recently told Government Technology.

The threat of the ‘transit death spiral’

Bioengineering company Genomatica released a study on July 30 that shows the extent of Americans’ anxiety: Nearly 25% report there has to be a COVID-19 vaccine available before they’ll ride public transit — and almost one-third say they’ll never again be comfortable using mass transit.

Low ridership, of course, leads to financial losses and strain for Metro and other transit agencies, which, if things don’t rebound, could result in more severe cuts and a “transit death spiral.”

Some of the nation’s biggest transportation systems, including in New York and San Francisco, have seen ridership plunge 90%. The New York Times’ Pranshu Verma has reported that transit agencies across the country “are projected to rack up close to $40 billion in budget shortfalls, dwarfing the $2 billion loss inflicted by the 2008 financial crisis.”

According to the Times: “This could plunge systems into a ‘transit death spiral,’ where cuts to service and delayed upgrades make public transit a less convenient option for the public, which prompts further drops in ridership, causing spiraling revenue loss and service cuts, until a network eventually collapses.”

That’s a grim prospect for those who aren’t afforded the luxury of opting to drive instead of taking the bus or light rail. They depend on public transit to get to the doctor or the grocery store. And to make matters worse, they already may be at greater risk because of their age or a health condition.

Guidance from public health experts has told us to reduce the risk of infection by maintaining physical distance and avoiding enclosed spaces, which can be difficult on buses and trains. And despite safety measures and modifications, including a mask mandate, protective shields around drivers and reducing seating by 50% to promote social distancing, the risk of exposure can’t be reduced to zero, especially for front-line transit workers.

In the Houston area, COVID-19 cases among Metro workers have been disproportionately high compared to Harris County overall. Transportation writer Dug Begley reported last month that roughly 2.2% of Metro’s 4,200 employees had tested positive for COVID-19, compared to 1% of the county population. As of Aug. 3, Metro reports that 171 of its employees and 48 contractors have tested positive for the disease. Begley points out that there have been more cases among Metro employees than there have been among the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority’s 9,800-person workforce.

But for transit riders, some hopeful news is found in recent research that suggests public transportation may not pose as much of a risk as many have thought.

Promising research from Japan and France

A study conducted by researchers at Sante Publique France found no links between the 150 coronavirus clusters in Paris between early May and early June and the city’s transit systems. The study was published on June 4, and as of July 15, four clusters — out of 386 total — were found to have originated on public transit, according to a Scientific American article quoting Le Parisien newspaper.

No clusters have been linked back to commuter trains in Japan, where most clusters have been tied to places where people are in close contact, such as gyms, bars and venues for live music and karaoke.

Because of relatively low testing rates and a lack of contact tracing in the U.S., the connection between public transit and COVID-19 infections is not clear.