For over a year, Houstonians have worked, studied, played and conducted virtually all forms of life at home under quarantine conditions in order to limit their exposure to, and the spread of, COVID-19.

Some have found the home to be a place assured of comfort and safety. But for others, the transition to a complete home life was far from seamless—for essential workers, it was impossible.

As part of the Urban Edge’s ongoing “COVID-19 and Cities” series, the Kinder Institute for Urban Research is examining the urban landscape a year after the pandemic began. These stories take a look back on the past year and ahead to what will be different in the years to come.

For families with little to no access to the internet, air conditioning, babysitting, home repairs or safe outdoor spaces, home life was not entirely a space of respite, presenting a host of new physical, emotional and spatial stresses while exacerbating existing ones. Under lockdown, domestic stressors could emerge from a range of environmental factors (heat stress, pests in the home, leaks or unsealed windows), site-related factors (difficulty accessing utilities and repairs, being cut off from medical services, limited or no home internet access for work or study), or social ones (insufficient child care support, overcrowding).

We know that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected low-income families. The question is: how?

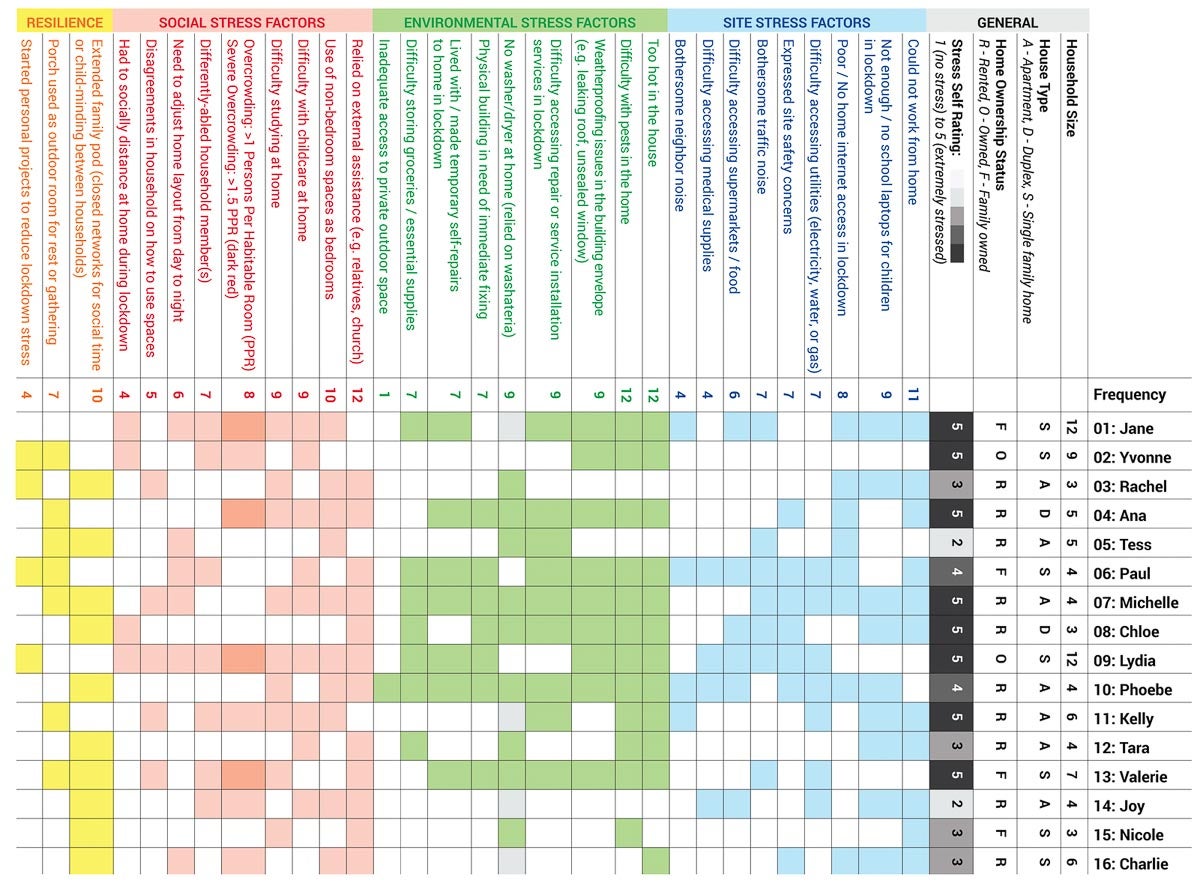

Stay-at-home Stress is a spatial survey of residents’ lockdown experiences at home in Houston’s Fifth Ward. With the support of Rice University’s COVID Research Fund, and in collaboration with the Center for Urban Transformation, we conducted video interviews with 16 low-income residents, and produced detailed plan drawings of each home describing how the 16 households lived through the 2020 stay-at-home order as well as its aftereffects. In this way, the crisis would be rendered not only in charts and graphs, but in specific spatial terms.

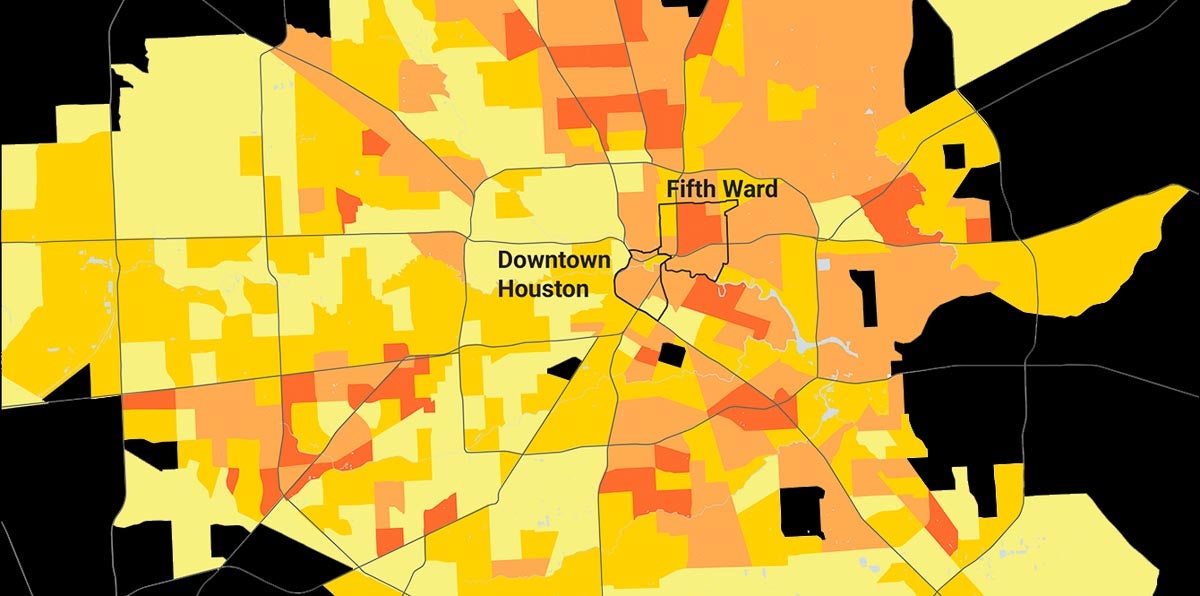

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index takes into account four factors of social vulnernability: socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status and language, housing and transportation.

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

As determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), most of the Greater Fifth Ward area’s population is considered to be at a high level of vulnerability. The SVI takes into account four factors—socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status and language, housing and transportation—that can place residents of socially vulnerable areas under extra duress during a public health emergency such as a pandemic.

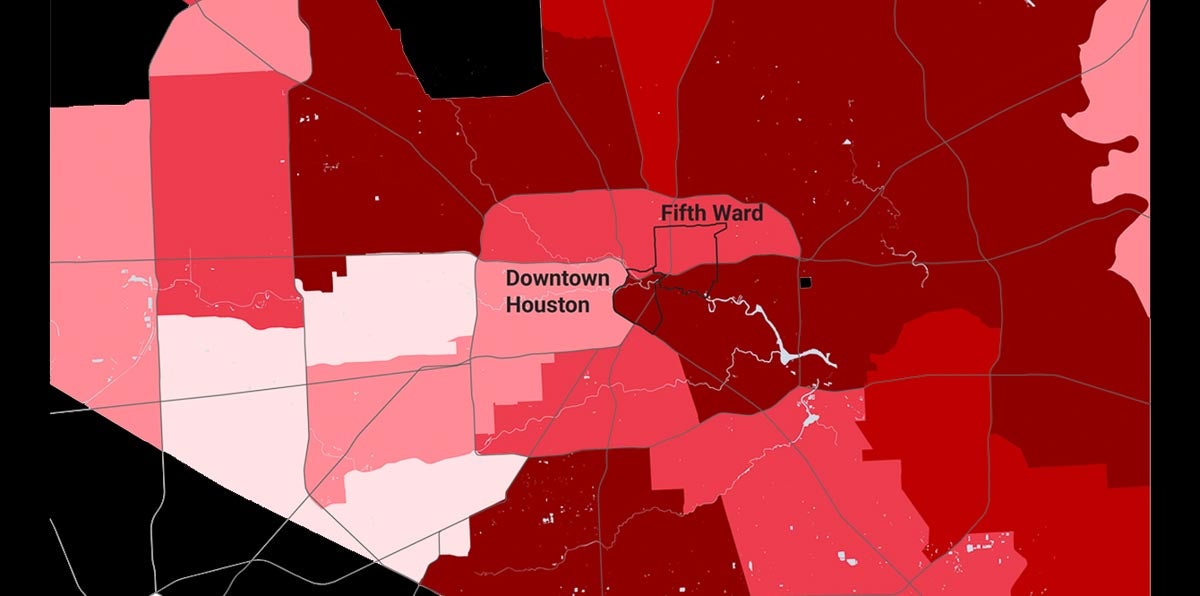

In a large portion of Fifth Ward — about half — 13–20% of residents have three or more health-related risk factors for severe cases of COVID-19 that would require hospitalization; while 11–12% of residents living in the other half of the neighborhood have three or more health conditions that place them at a higher risk of being hospitalized with the disease, according to 2018 Health of Houston data. Other census maps reveal demographic disparities: households in Fifth Ward and other neighborhoods east of Houston’s downtown earn, on average, significantly lower incomes than regions immediately west of downtown. Yet, its census tracts in Fifth Ward are not homogeneous, and exhibit a range of household sizes and percentages of families with children living below the poverty level.

A large share of Fifth Ward residents have three or more health conditions that place them at greater risk of a severe case of COVID-19.

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

Considering all of this, we placed the focus of the Stay-at-home Stress study on Fifth Ward, the population of which could be seen to be at greater risk of challenges related to COVID-19 based on its share of residents over 65 years old, households without internet access, children living with single parents, persons with a disability, households without a car, unemployment, low-wage earners and household incomes less than $15,000, among others).

How have underserved residents personally experienced stay-at-home stress? To help answer that question, our team interviewed 16 residents about their living situations. Here are the results of four of those interviews:

(Note: Pseudonyms are used instead of the participants’ real names.)

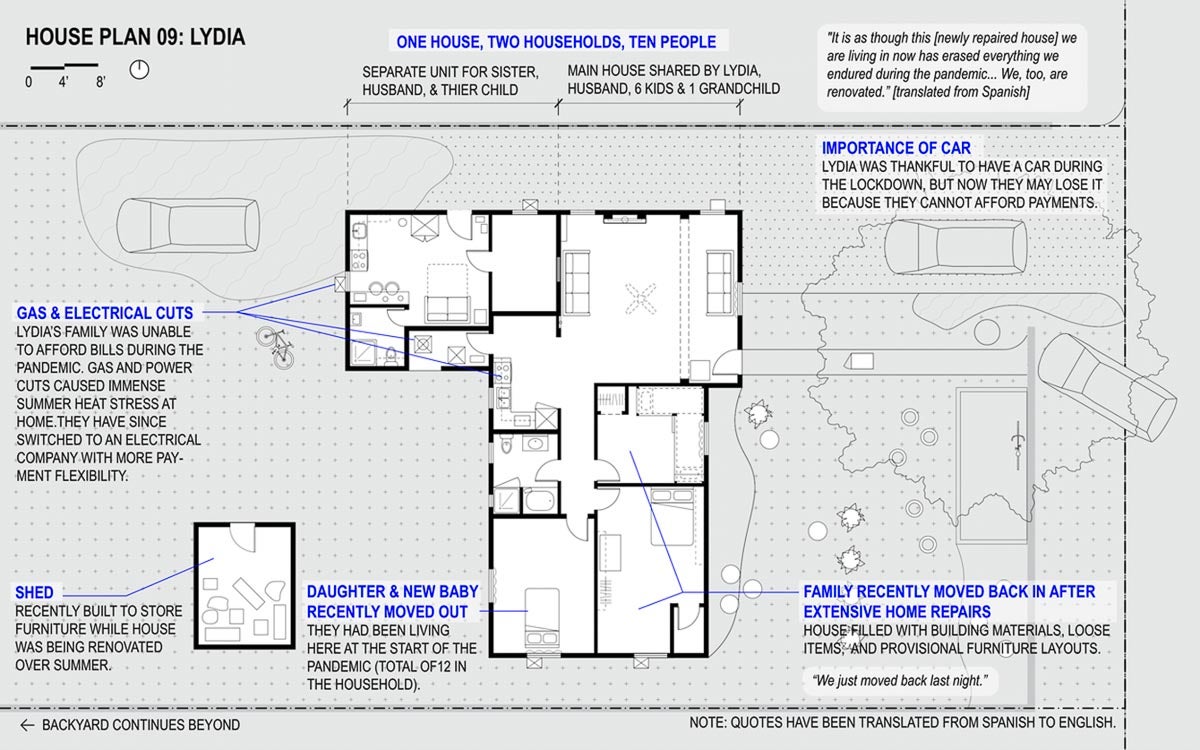

Lydia

(female / homeowner / looking after children full time)

Housing type: single-family home with attached secondary dwelling; original home built in the 1950s

4 bedrooms (including attached secondary dwelling) / 1 bathroom / approximately 1,500 square feet

Household size: 12 (four adults, eight children)

Self-rated stress level (on a scale of 1 to 5): ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Two families reside in a three-bedroom single-family home and its attached one-bedroom secondary dwelling: Lydia’s family of seven and her sister’s family of three. Lydia’s daughter and her newborn lived with them early in the pandemic, making a household size of 12. Located in the 100-year floodplain, their house had been badly damaged during Hurricane Harvey, and renovations to address those damages were completed mid-pandemic using relief funding. From 2017 until then, the families had been living in the house with major storm damage to the walls, floors and roof that made the house vulnerable to leaks from rain. When we spoke, she showed us a large unrepaired hole in the ceiling that the funds were not able to cover.

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

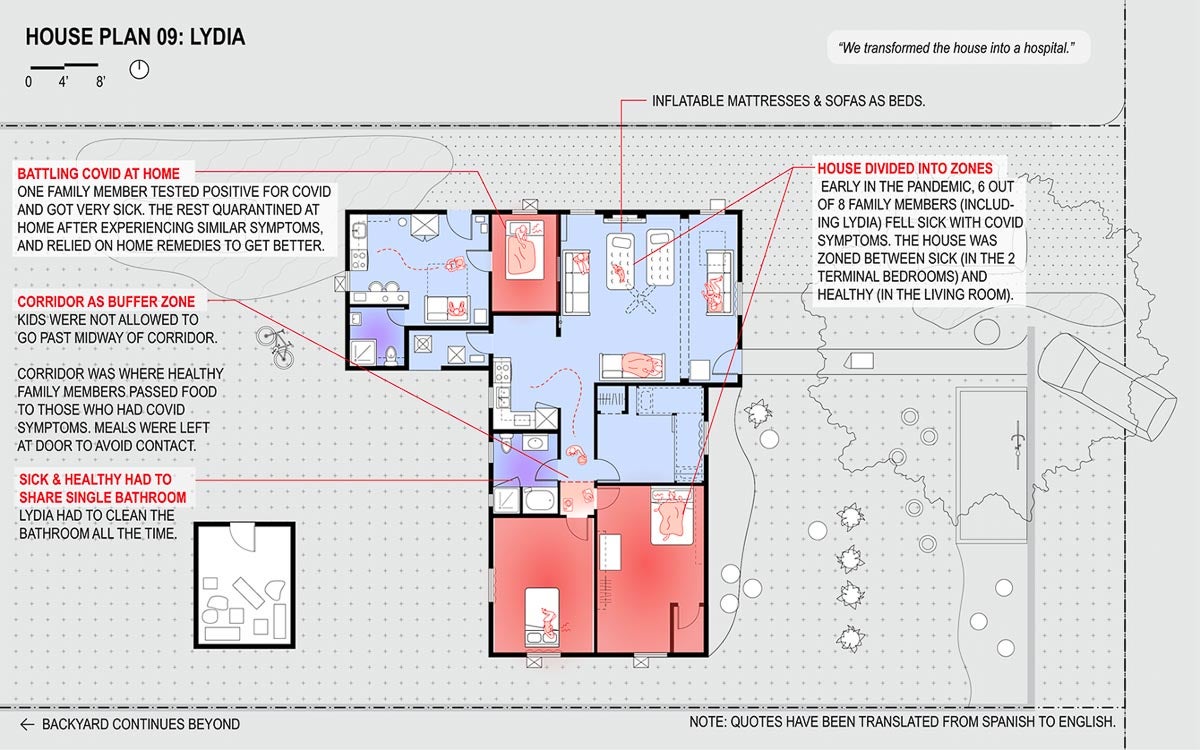

During the lockdown, Lydia’s family home doubled as a “hospital” and a “school.” Nearly all of her family members fell sick with COVID-19 symptoms and one family member tested positive. Lydia described the stress of sharing a single bathroom when almost all family members fell ill with COVID-19 symptoms. She also described their efforts to socially distance under one roof by zoning the house between the sick (in the bedrooms) and healthy (in the living room), with the corridor being a middle ground where Lydia would distribute food to each person. It was particularly difficult to transition six children of different ages to home schooling — two of whom have autism and needed closer care. The constant noise of children at home left Lydia without much respite.

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

Furniture layouts were changed from day to night to accommodate sleeping, studying and family activities. The house only had one working AC unit in the living room, adding to physical stress over the summer. (Heat turned out to be a big stress for most of the families we spoke to; most families congregated and even slept in their living room or wherever the AC was located.) Lydia and her sister took turns watching children and picking up groceries from local organizations (a frequent task, considering how much food was required for their large household, and there was limited cold-food storage in the home).

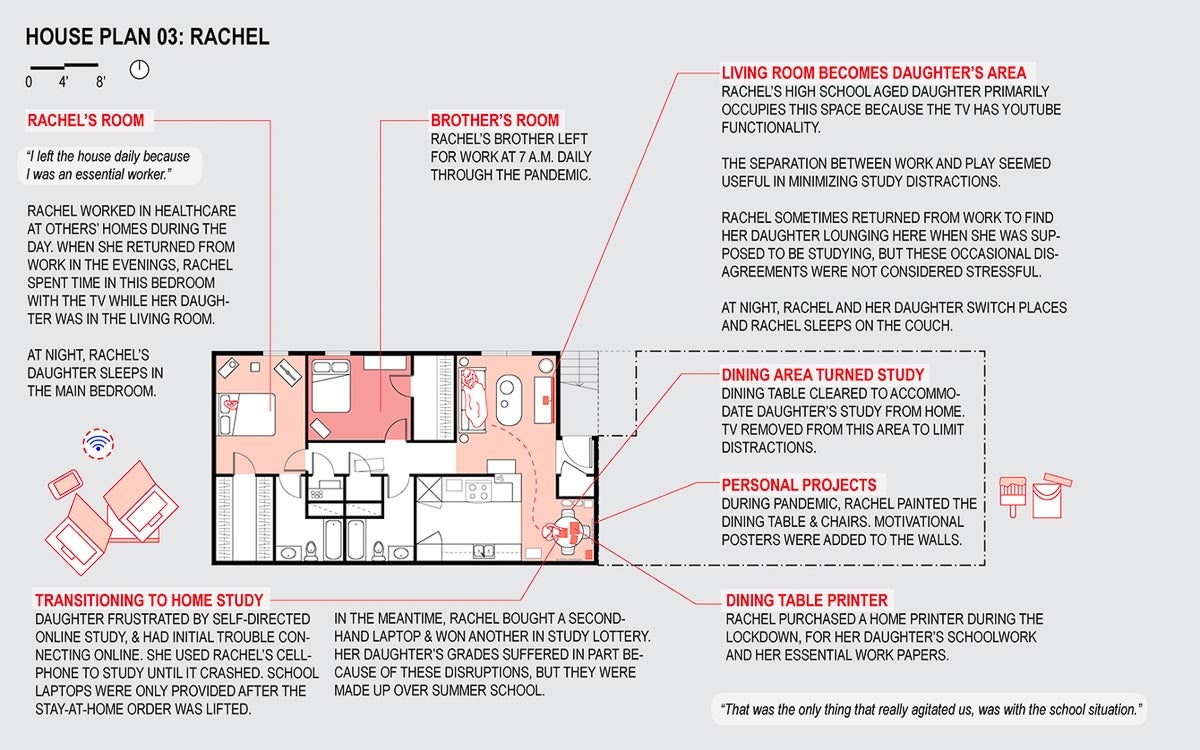

Rachel

(female / renter / essential health worker)

Housing type: apartment in complex built in the 1930s

2 bedrooms / 1 bathroom / approximately 1,000 square feet

Household size: three (two adults, one child)

Self-rated stress level (on a scale of 1 to 5): ♦ ♦ ♦

Rachel is an essential health worker who went to work daily though the stay-at-home order. She lives with her high school-aged daughter and brother (who also worked outside the house throughout the pandemic). Rachel slept in the living room at night, while her daughter took over the living and dining rooms for study and recreation during the day when the house was empty.

Transitioning to remote learning proved difficult for Rachel’s daughter, who had limited access to a laptop and initial trouble connecting to the internet. These disruptions caused her daughter’s grades to suffer, though they were subsequently made up in summer school.

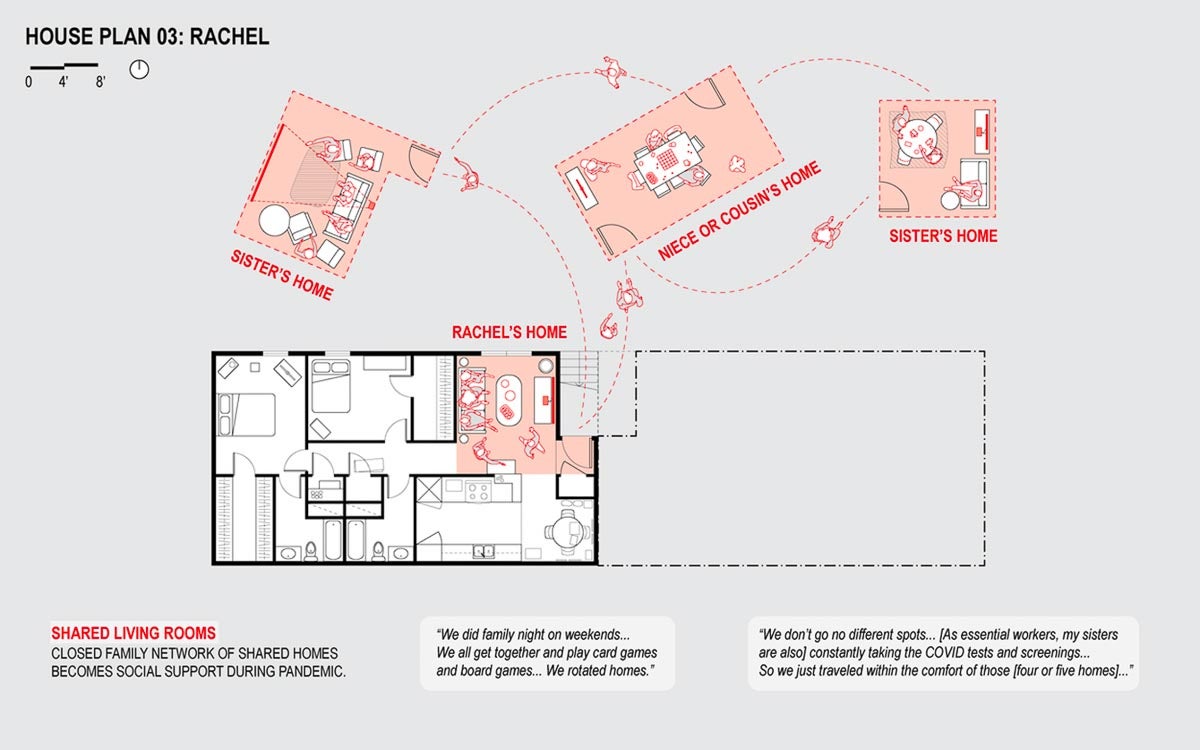

Rachel is also part of a closed social network of family members, including her sisters, cousin and niece. Rachel and her sisters are all essential workers, and regularly are screened and tested for COVID-19. Thus, Rachel and her family members are able to safely get together on weekends to play cards and board games.

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

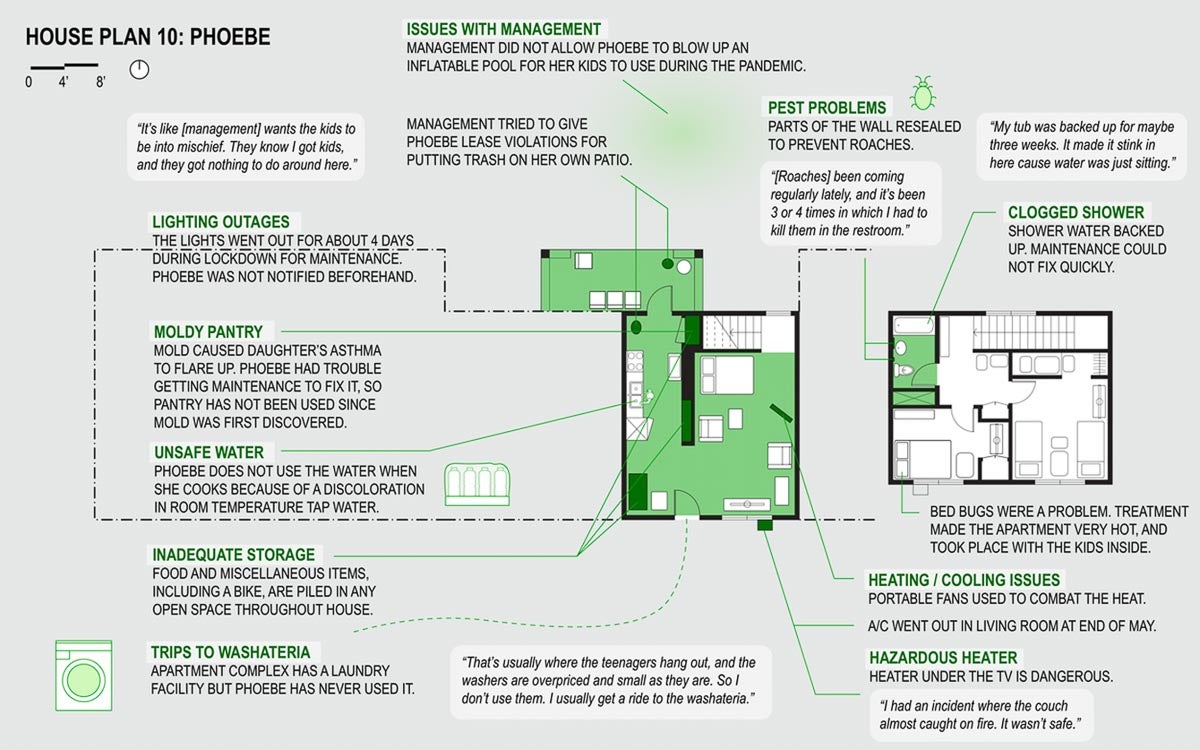

Phoebe

(female / renter / works from home — shift work on laptop)

Housing type: two-story apartment in large complex built in the 1930s

2 bedrooms / 1 bathroom / approximately 1,100 square feet

Household size: 4 (3 children, 1 adult)

Self-rated stress level (on a scale of 1 to 5): ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

During the pandemic, Phoebe had to obtain a laptop to do shift work from home, and struggled with Wi-Fi access because many companies did not provide internet services in their area.

Most of her concerns stem from poor housing maintenance, slow repairs and a sense of being targeted by building management. In their two years in the apartment, her household has experienced bedbugs, asthma-inducing pantry mold, a three-week-long period of time with a clogged tub, broken AC unit through summer, and a four-day electricity outage without warning.

She was locked out from her mailbox for seven months during the pandemic, causing her to lose her food stamps and miss important information. She described having received unfair lease violations for simple acts, such as inflating a pool for her children in the shared greenspace behind her apartment building during the lockdown. Her dad or sister would stay over occasionally to help with child care.

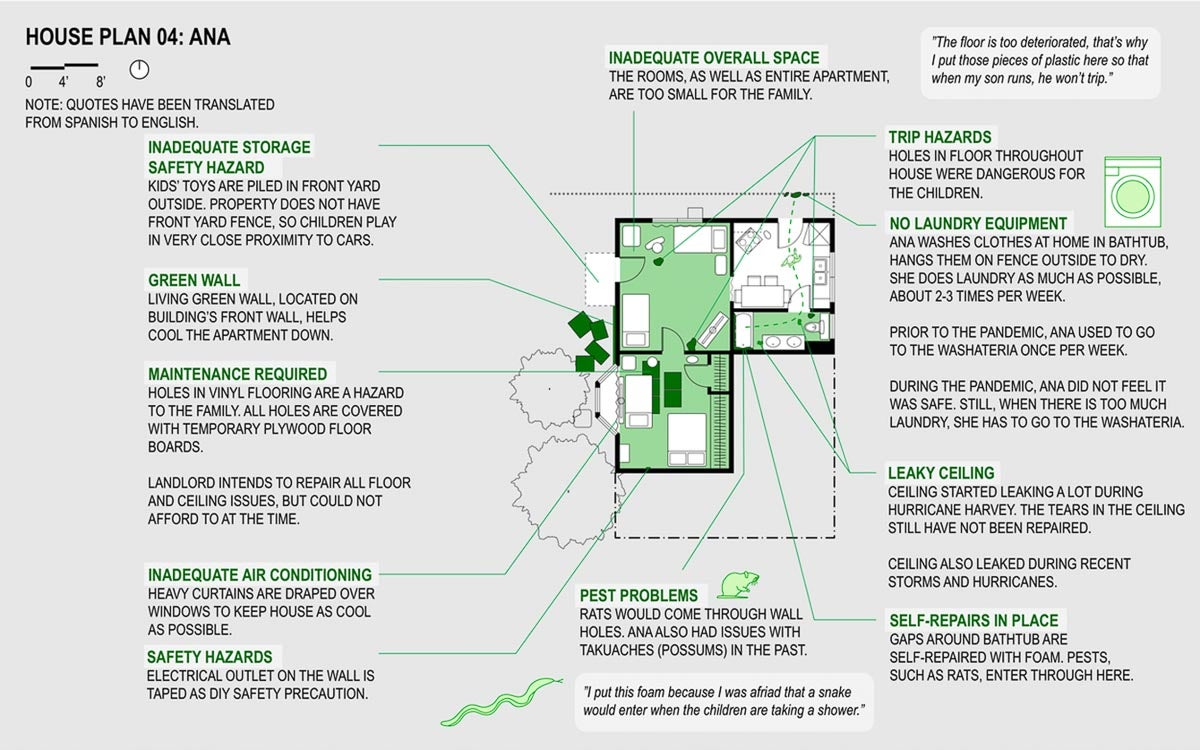

Ana

(female / renter / looking after children full time after losing housekeeping job in pandemic)

Housing type: Duplex built in the 1950s

1 bedroom / 1 bathroom / approximately 650 square feet

Household size: Five (three adults, two children)

Self-rated stress level (on a scale of 1 to 5): ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

Even before the pandemic, Ana was living with home stress due to overcrowding. Her household of five (herself and four sons, ages 3 to 21) shares a one-bedroom duplex. During the stay-at-home order, home overcrowding did not only affect sleeping arrangements, it also impacted her school-age child’s ability to concentrate on schoolwork. Ana expressed deep concerns about how they would all live in the small space if someone caught COVID-19. Ana lost her housekeeping work because of the pandemic, which created additional financial pressure. Ana’s biggest concern was the house’s need for physical repairs: from holes in vinyl flooring that posed tripping hazards to ceiling tears and water marks, loose electrical outlets and poor sealing around the bathtub that brought pests indoors. While waiting for the owner of the duplex to make repairs, she has repaired a gap in the bathroom wall herself, as well as covered damaged flooring with cardboard.

Pandemic stress intensified existing pre-pandemic stress

Despite the survey’s small sample size, the stories of these 16 households illustrate how pandemic stress related closely to preexisting vulnerabilities at home. Stressors that require immediate attention include overheated homes without air conditioning, pest control problems beyond the individual household, trouble accessing utilities (no internet, electricity outages), breaks in the building envelope causing weather to enter habitable spaces in the home, and delayed landlord repairs (non-functioning HVAC, blocked mailbox access, even holes in floors or lack of fire escapes, which create physical safety hazards).

When residents were asked to rate household stress levels on a scale of 1 (“not stressed at all”) to 5 (“extremely stressed with no way to make my own living situation better”), eight of 16 participants gave themselves a “5”, and two scored themselves at "4". All 10 of those households identified excessive indoor heat, pests and weatherproofing issues in the building envelope as major preexisting sources of stress that made the pandemic transition much harder. By contrast, the two residents who self-scored themselves at “2” were able to environmentally control their home, transition work and study online with relative ease, and maintain some continuity of domestic life with the support of extended family.

Residents were asked to rate household stress levels on a scale of 1 (“not stressed at all”) to 5 (“extremely stressed with no way to make my own living situation better”) based on site, environmental and social stress factors, as well as resilience levels.

Image source: Stay-at-home Stress

Stresses aside, families also described resilience measures: 10 families had some form of extended family network that could be relied on for child care and external support, while seven families used their porches as open-air rooms for rest and social gathering.

Ana, Lydia and others relied heavily on local food distribution services —highlighting the importance of community organizations in supplying food to families through the crisis. Neighbors also supported each other: Michelle drove other single mothers living in her apartment building, who did not have cars, to get groceries.

Additionally, the survey found just how much families with children relied on nearby public parks. When parks closed down, front yards, backyards and private outdoor spaces became important outdoor areas for rest and play; however, they also brought about concerns for child safety and proximity to traffic. As most households did not own an in-house washer or dryer, the washateria was another essential urban amenity.

Beyond the COVID-19 emergency period itself, the next work year is likely to be particularly difficult for residents who lost employment during the pandemic or are unable to work from home (e.g., essential health care workers). Low-income families may continue to rely on external support for food and essential supplies, and on family or friends for lifts to get groceries, if they do not have access to a drivable car.

The next school year is likely to present additional stress for parents trying to maintain conducive study environments for children at home, particularly large households with different child-learning needs. Lack of home internet access and delayed school laptop/hotspot distribution may also be a major setback for school-age children expected to keep up with online study materials.

The next summer may continue to bring stay-at-home discomfort and health hazards, not only during pandemics, but also between crises. Households without adequate cooling or consistent access to utilities are likely to experience similar or worse heat stress in a warming climate, particularly if confined to homes for long periods of time.

The next storm season is likely to affect more families than just those living within Houston’s designated floodplains. Case in point is February’s winter storm, which dealt an additional blow to families already living in homes that leaked or had unpredictable interruptions in electricity service.

I am reminded of Lydia, whose story outlined above reflects a real stress for families in the floodplain; and of Michelle, whose rental apartment’s thermostat was broken throughout the pandemic summer, making the house unbearably hot. In a follow-up call in December, Michelle noted that the thermostat still had not been repaired by building maintenance, which left her family vulnerable to the cold. If her dwelling already lacked environmental control, I cannot imagine what her family went through during the February freeze.

These compounding crises of late reveal the precarity that existed before the pandemic for historically underserved residents in the most intimate spaces of their homes. Recognizing the unequal shape of pandemic experience, this spatial survey reminds us not to romanticize or universalize the ease of working or living from home, and to give voice to the residents who been forced to bear the brunt of the pandemic.