Mariah Iles was a single mother and six months pregnant when she came across the notice in a weekly community paper. There was a picture of a young woman, like herself, promising she could get her GED with the help of YouthBuild, an international organization that helps young people get credentials and training to enter the workforce.

After a tumultuous childhood that included physical and sexual abuse, Iles had not completed high school. She had a son already and was about to have another. She had been homeless and in and out of the juvenile justice system. "I took the chance and made the call," said Iles, speaking at a Kinder Institute event at Rice University this week.

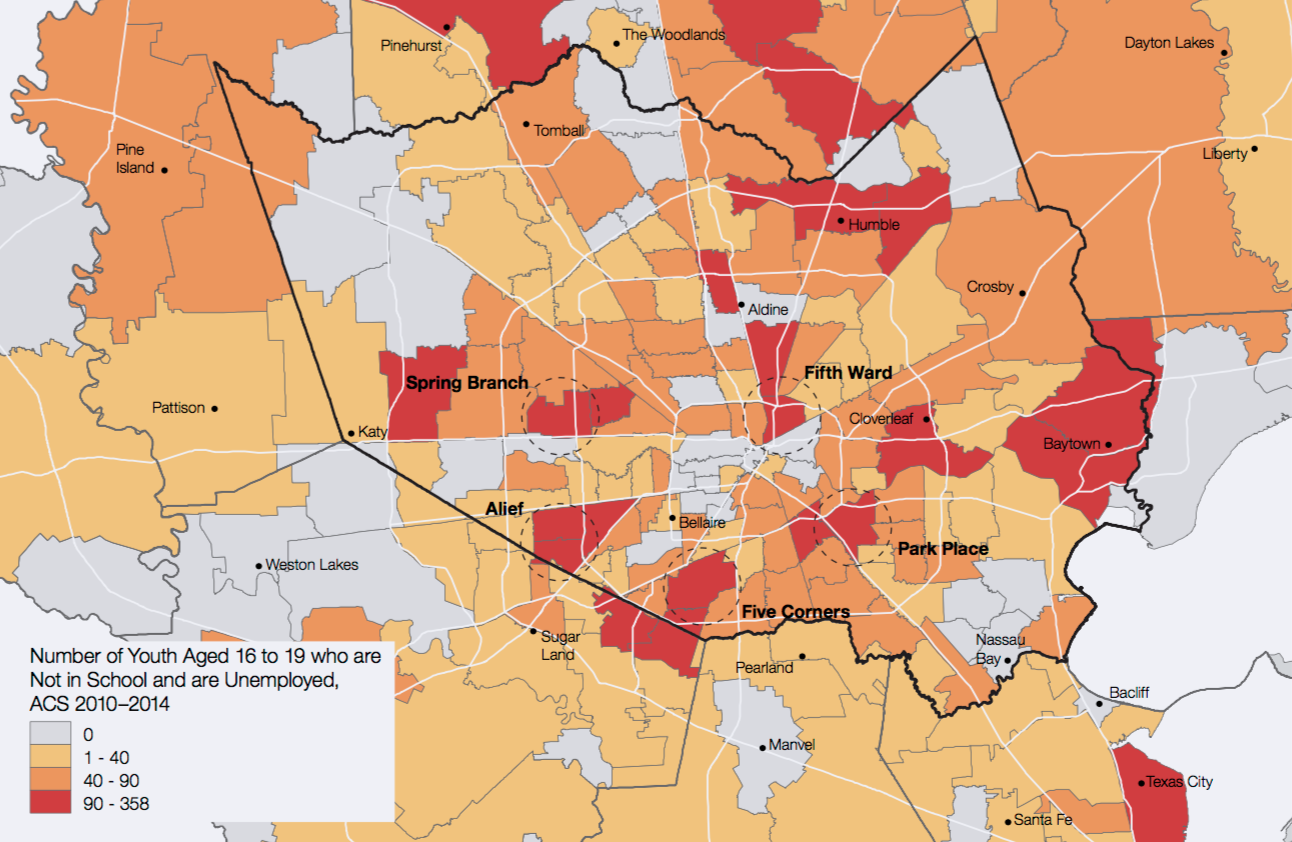

In Houston, there are an estimated 111,000 young adults ages 16 to 24 who aren't in school or employed, representing roughly one in seven of all young adults, according to a new report from the Kinder Institute. Many of them have a background similar to that of Iles.

Despite the country's gradual return from recession, a growing number of young people are still lagging behind, in part because of their struggle to secure educational opportunities or a job. "It is a terrible loss that we will pay a price for," said Kinder Institute founding director Stephen Klineberg at an event Wednesday coinciding with the release of a study from the Kinder Institute that addresses this population of "disconnected youth."

The report highlights common barriers like access to education; the feeling of disengagement young people may feel from schools and the workforce; unreliable transportation; the challenge of criminal background checks; and the impact of health problems complicated by a lack of insurance.

The report also pointed to programs, like YouthBuild, that offer pathways to help young people improve their circumstances, and it offers recommendations on how to reengage a group the Kinder Institute also terms "Opportunity Youth and Young Adults."

Roughly 14 percent of Houston's youth ages 16 to 24 fall into the category of disconnected youth, putting the Houston area roughly on par with other big cities such as Dallas and Atlanta. Unique to Houston's population, however, is its relatively high share of individuals in this category who have a high school diploma. Nearly 80 percent of Opportunity Youth and Young Adults here had finished high school, according to the report, compared to roughly half of the national population of disconnected young people.

Texas also has legislation that funds public education for students up to 26 years old, in order to support special reengagement efforts, like the successful work in Pharr-San Juan-Alamo ISD. Lili Allen, an associate vice president at Jobs for the Future, noted that Houston is in a "relatively strong position to do something about the opportunity youth crisis." Indeed, 72 percent of Houston's disconnected young people say they had a positive outlook for their personal future, according to survey data.

But Houston also presents specific challenges too. Transportation was a persistent concern brought up by both young people and service providers interviewed for the report. In a sprawling metropolitan area, connecting people to jobs who lack reliable transportation is a challenge for all stakeholders. "They can quickly lose an opportunity just based on transportation access," said Kimberly Johnson-Baker, one of the study's authors.

The report also found that despite common stereotypes about "inner city" neighborhoods, in the Houston area, some of the highest numbers of out of work and out of school young adults are located outside the urban core, exacerbating transportation challenges and highlighting the need for social services to be spread throughout the region. And in one of the most economically segregated cities in the country, the far-reaching implications of concentrated poverty fed into the local landscape of Opportunity Youth.

The study found that Houston's disconnected young people are disproportionately black and Hispanic even though Kinder Houston Area Survey data consistently show that black and Hispanic communities understand the importance of education more than white Houstonians, who tend to think there are still plenty of good jobs available to people without a high school diploma. Indeed, according to the report, by 2020 about 65 percent of all jobs will require a high school diploma. "Education has become absolutely essential," said Klineberg.

Iles knew education was critical for her future. When she thought about the life she wanted for her children, it was nothing like the one she knew. Her mother was 18 when she gave birth, and shortly after, Iles was placed in the care of another family member. When she later reconnected with her father, it proved to be a toxic connection. Before a crowd of service providers, employers and others, Iles shared that her father sexually abused her for five years before she tried to stab him and kill herself. She was 13.

"When the police got to my dad's house, I felt so guilty and needed to protect my dad, so I didn't say a word," she said. Instead, she was charged with aggravated assault and sent to the Texas Youth Commission for a year. She would return several more times before turning 18 for parole violations. By that time, she had already had two children who were taken from her custody; she said she thinks about them every day. Since has lived in shelters, halfway homes and in cars. "I had lived more life than I wanted," she said.

Through all this, Iles, now 23, knew she loved to learn and knew she was capable. Working with YouthBuild connected her to people who she said took a hands-on approach to helping her chart her future. With their guidance, she earned her GED and enrolled in Lone Star College, where she plans to complete her business and management degree. "I want to be and do so many things," said Iles, including starting a shelter for women and children.

Though the study focused on teenagers and young adults, it found that many of their hurdles begin in childhood. Young people interviewed for the report said they felt disengaged from school at an early age, and many bore the burden of poverty well before entering high school.

From stress and mental health challenges, to pressures to drop out and provide for their families, respondents shared common experiences often stemming from poverty. And those challenges helped lead to many of their current situations.

"The issue of joblessness is intimately related to other issues," noted Charles Rotramel, executive director of Houston ReVision, a nonprofit that works with youth who have been through the juvenile justice system. "It's hard to get to a job every day if you are dealing with a mental health issue, or a substance abuse issue or you're sleeping in your car."

In addition to a coordinated approach between nonprofits and service providers, experts at the Wednesday event touted the need for early intervention in schools, more relevant curricula, and "earn and learn" opportunities that allow young people to work and develop job skills simultaneously. The panelists also called for clearer guidance on post-secondary education and career pathways; a reconsideration of employment background checks, which tend to reenforce racial disparities within the justice system; as well as a loosening GED requirements.

But before employers and service providers can connect disconnected young people to jobs or education, noted Iles, it's critical to address their most urgent needs first. "You're talking to me about college but I don't even have a place to stay," she said, recalling the attitude of young adults who have been in her shoes.

Inaction, warned the Kinder Institute's report, could cost taxpayers an estimated $30 billion in the Houston area, based on estimates. "Given the vast numbers of disconnected young people--and the cost of inaction--the time to consider a different approach is now," the report concludes.