As Houstonians continue to stay put in their homes to slow the spread of the new coronavirus so that our hospitals aren’t overwhelmed and more people don’t die, we need to be looking ahead to the future. Specifically, we need to be thinking about American cities in the wake of the pandemic and how to safely open them up again when we end or relax social distancing measures.

Pandemics come in waves. In 1918, there was an initial wave of influenza deaths before social isolation efforts flattened the curve in large American cities such as New York, San Francisco and St. Louis. However, when social distancing efforts were relaxed, a second wave hit some cities, including San Francisco and Philadelphia.

The 1918 flu pandemic caused tens of millions of deaths worldwide, including 675,000 in the U.S.

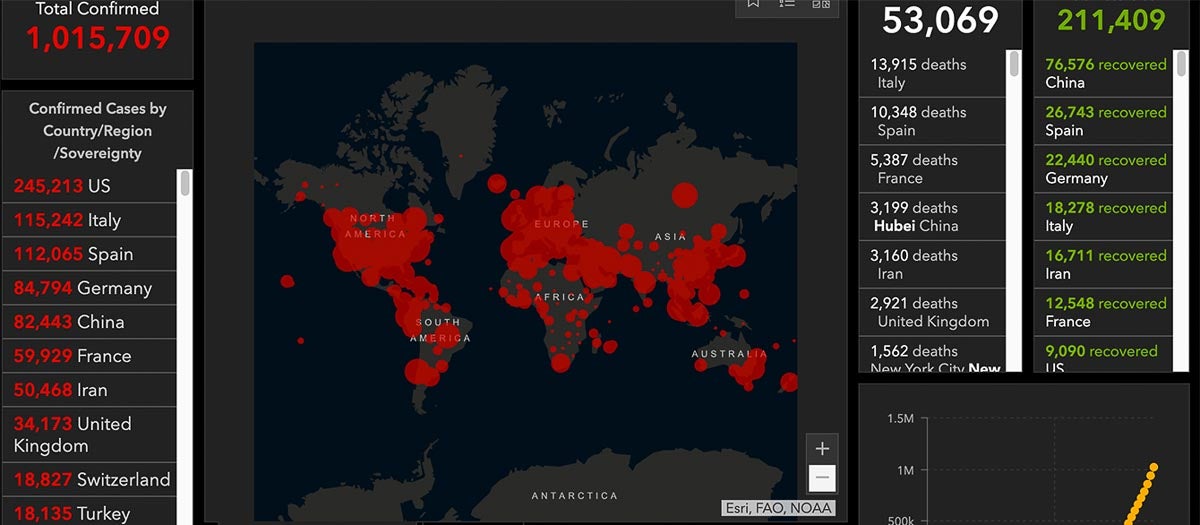

So far, there have been over 1 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, killing more than 54,300 people. In the U.S., where the total number of deaths has surpassed 6,000, there have been more than 245,600 cases, according to Johns Hopkins University. Cases are doubling every three days in Harris County.

Our ongoing “COVID-19 and Cities” coverage examines the pandemic’s effects on Houston and other metropolitan areas, both now and once the outbreak is over.

Kinder Institute Director Bill Fulton recently wrote about many of the changes we’ll likely see in cities as a direct result of the pandemic. Fulton sees positive outcomes: A renewed focus on public health; an increase in remote work arrangements, leading to more activity in neighborhoods; greater flexibility in public transit options; and more sophisticated urban design.

We can learn from this crisis

Though optimism is a tall order in times as difficult as these, ultimately, our society and our cities can become more resilient if we take advantage of the learning opportunity presented by the pandemic. Richard Florida says squandering that opportunity worries him the most.

“I hope we don’t collectively forget. That’s what really keeps me up at night is that we forget about this and it comes back to bite us again,” says Florida, a university professor at the University of Toronto’s School of Cities and Rotman School of Management and the co-founder of CityLab. “These [outbreaks] are happening and they’re accelerating (SARS, the swine flu, Zika, MERS). But hopefully, we learn from this one and we get ready for the next ones and we’re ready for them when they occur. And we don’t forget.”

However, as Florida notes, the history of pandemics shows we tend to forget.

“The 1918 flu pandemic was followed by the roaring ‘20s. I want this (pandemic) to do some good and make us more civically and socially minded and get us away from this hyper materialism,” Florida says. “But I look back and go, that’s not what happened before.”

Florida was speaking by Zoom from his bedroom — because his 2- and 4-year-olds were “running around like maniacs” — with Steven Pedigo, the director of the LBJ Urban Lab at the University of Texas at Austin. The conversation, titled “On the frontline: Restarting our cities,” covered research conducted by Florida and Pedigo and focused on what America can expect in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and how the country can best rebound by preparing now to reopen cities.

Florida says the current pandemic has reminded him and others who work in urban development and urban economic development how important health crises are in shaping and reshaping our cities.

“I think it’s made us all wake up and realize how important and potentially devastating these pandemics are and how they reshape our society, our economy and our cities.”

A screengrab shows John Hopkins University’ s dashboard of COVID-19 global cases and deaths. The totals are updated daily.

How will our daily lives be different?

No, cities won’t go away.

“[Pandemics have] never really altered this arrow of urbanization — the clustering of people and ideas and firms and businesses,” Florida says. “Infectious disease is a horrible force. It thrives off clustering, it transmits through clusters. But urbanization is the more powerful force.”

Geographic divides will grow

“I think what this is likely to do, unfortunately, if we if we’re not conscious of it and if we don’t plan for it, is it’s likely to reinforce geographic divides,” says Florida.

“This thing that we call winner-take-all urbanism, where a few places (the superstar cities such as New York, London, Los Angles), as well as the tech hubs (cities like Austin, Seattle and Boston), have really benefited, I think those patterns will be reinforced.”

Socio-economic divides will be magnified

“What we’re seeing now is a class divide that parallels the divide we saw in the early 20th century — in 1918 and 1920 — leading up to the Great Depression.”

At that time, Florida says, society was highly unequal. Then, as today, there were inequalities in the way people live and work. Leading up to the Great Depression, “affluent capitalists, business owners and managers were able to work on the hillsides in places like Pittsburgh and Detroit and in the Upper East Side around Central Park in New York. They had private hospitals to serve them. They had servants to bring them things.”

Meanwhile, factory workers lived in crowded tenements and worked in cramped factories — cheek by jowl — supporting the World War I war effort.

Today, affluent, professional, white-collar workers have the luxury of working remotely, in the safety of their homes.

Smartphone location data analyzed by the New York Times showed many lower-income workers continue to leave their homes to go to work, increasing their exposure to the virus, while those who earn more and are able to work from home limit their exposure.

“We get stuff delivered to us. We use Instacart and Uber Eats and delivery services, whereas the frontline workers — 30% of our workforce — people who work in transit, people who work the buses, people who work the grocery stores, emergency responders, nurses aides, retail clerks are exposed to this virus in their daily work,” Florida says. “They’re saving us and they’re exposed when they transit to work.”

The class divide, he contends, is going to be magnified but he hopes it will give rise to rewarding the nation’s working class, as it did following the 1918 pandemic. Though he’s hopeful it won’t take an entire decade like it did 100 years ago.

“Some of these workers are organizing,” Florida says. “They’re calling on their employers — Instacart, Whole Foods, Amazon — to pay them better and get them the [protective gear] they need.”

On Thursday, Amazon announced plans to begin temperature checks and distributing face masks to employees in its warehouses and Whole Foods stores by next week.

What are the factors that seem to leave cities and communities more vulnerable or protected?

Some U.S. cities seem to be having more success than others in slowing the spread of COVID-19. While that success can be attributed to early shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders in cities like San Francisco, it’s important to consider the jobs and professions of a large part of that city’s workforce compared to places like Detroit, New Orleans and New York.

“New York City has Manhattan but those outer boroughs — the largest (COVID-19 impact) is happening in the Bronx, in Staten Island, in Queens, which is not a yuppie land of professional workers,” Florida says. “It’s filled with working-class immigrants and poor and disadvantaged people.”

Cities with a greater rate of affluence, higher-income jobs and highly educated residents — all of which increase the number of people who can work remotely — are having better outcomes, Florida points out, than cities like Detroit or New Orleans.

“[We’ve got to protect] service workers and we’ve got to protect underserved communities because it’s the right thing to do,” Florida says. “And if we don’t, the disease is going to spread [in those communities] and it’s going to spread everywhere.”

Health and fitness, red vs. blue and children

Florida points to other factors that make some cities more vulnerable, such as levels of health and fitness. Smoking, obesity and underlying conditions are more prevalent in the populations of some cities than others. Blue states and blue cities seem to be taking the pandemic much more seriously and social distancing more than red, he says.

“There’s a correlation there. Blue states and blue cities have higher levels of educational attainment, they have more professional workers and higher incomes.”

Childlessness also leads to better outcomes.

“Children are vectors,” says Florida. “Cities that have more kids may be more vulnerable. ‘Kid’ cities have more kids and ethnic communities, religion and social capital, things that we really care about in America.

"What is the base case of social capital in the world? Italy, and particularly the northern part of Italy. Deep social capital, deep civic ties, multi-generational families, highly religious. What are the vectors for transmission? Multi-generational families, churches and temples. I’m not making normative judgments. But places that have deep social capital, highly religious beliefs and multi-generational families are more exposed.”

How do we prepare our cities to reopen and battle this virus for the long haul?

“I don’t want to be the bearer of bad news but we aren’t going to press a button after six weeks or eight weeks, whenever it is, and just pop back to normal,” Florida says. “We’re looking at a period of anywhere — now it’s hard to say — six months … to 12 months … to 18 months … where we’re going to be dealing with some version of this.

“We have to learn from the virus. We can’t do these things in the abstract.”

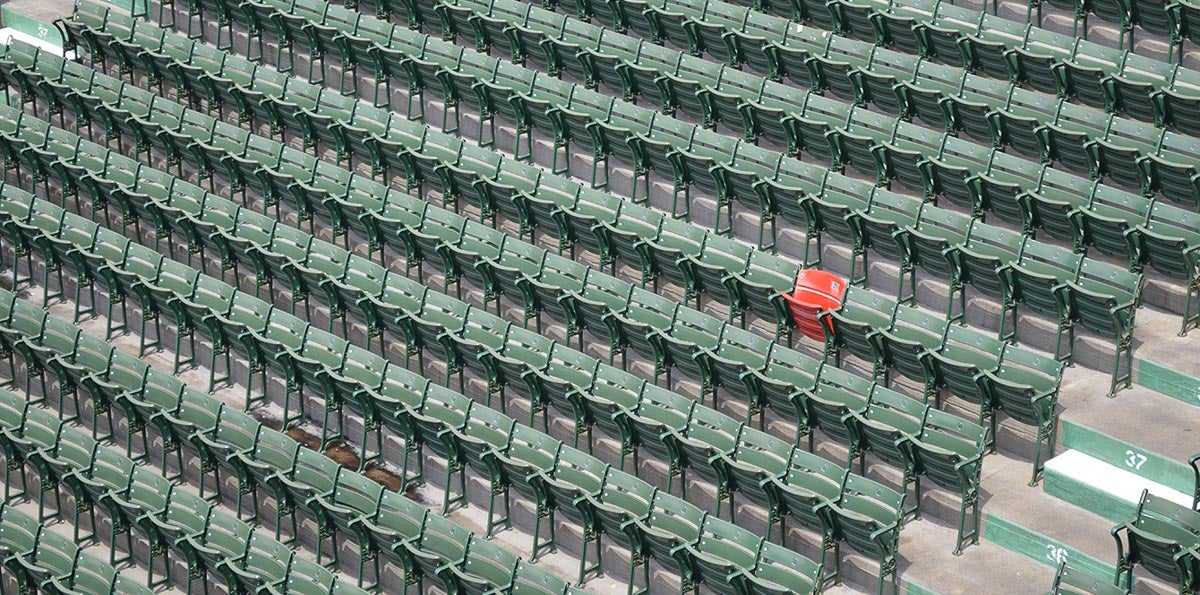

“The retrofit on airports — but also arena stadiums and convention centers — is going to be way bigger than what happened in the wake of 9/11. We’ve got to start now,” says Richard Florida.

Photo by Veronica Benavides / Unsplash

Four key things to prepare cities to reopen

1. Temperature checks

“When you see the pictures of people (in China and Singapore) wearing masks and getting a temperature check at the airport, these are all important,” Florida says. “Temperature and health screens [are needed] to know who has the virus. Antibody and serological checks [are necessary] to know who’s had it.”

2. Personal protective equipment

“We’ve got to protect our frontline workers better,” Florida insists. “We’ve got to get them the masks and gloves they need. The studies show that using the combination of mask, gloves, protective garb and hand-washing reduced the SARS virus by 90%.

“And it doesn’t have to look like a hazmat suit or some rag-tag bandana,” he says. “Why can’t we mobilize our fashion-design community and our clothing manufacturers to make personal protective equipment that’s safe and doesn’t look like hazmat gear?

“Sooner or later, I got to take my little girls back outside. They’re 2 and 4. Am I going to wrap them up in a surgeon’s mask and rubber gloves? No. But if they had cute little — and don’t laugh at me, Disney ‘Frozen’ gloves that look like Elsa and Anna and a little dress that looks like an Elsa and Anna dress, they can go to the playground or they can go to school.

“This is not rocket science in a country like America. You can design protective gear that is functional and looks like workwear (for when you go to the grocery store). Let’s get with it.”

3. Design for social distancing

“We’re already seeing this. … Where supermarkets like Whole Foods have tape on the floor (to mark 6 feet of distance) and this and that in circles in Denmark,” Florida says. “We’re going to have to do a lot more of that and do it better.

“And we have to ensure that our main-street businesses and creative economy survive. You can imagine Walmart, Amazon, big airlines, big companies, Uber getting with this. Equipping their employees. You can imagine the grocery chains really mobilizing to make sure that people are safe. Main-street small business? The small mom-and-pop restaurants? How are they going to learn about design for social distancing? The small independent theaters, the art galleries, the things that make our creative economy survive. That sidewalk ballet. Imagine walking down the street in Austin or Los Angeles or New York three months from now, with storefront after storefront shuttered because these businesses either couldn’t make it financially or don’t know how to reopen safely.

“At the same time that we provide the financial assistance packages, we got to provide the technical assistance — the small-business technical assistance — and Chambers of Commerce and economic development organizations can mobilize to do this now.”

4. Personalized service provision

“We’ve got to really think hard about airports and big civic infrastructure,” Florida says. “The retrofit on airports — but also arena stadiums and convention centers — is going to be way bigger than what happened in the wake of 9/11. We’ve got to start now. If you want to reopen that convention center, if you want to even think about an event like a South by Southwest, if you want to think about reopening the airports, (we’ll need) temperature checks, health checks, health screens, design for social distancing, protective gear for employees and protective gear for participants.”