The penny-farthing is a classic symbol of antiquity: it represents an age of burgeoning industrial wealth when local transportation mostly still involved a horse. But the bicycle is not as old as many assume — the modern “safety bicycle” arrived at roughly the same time as the modern automobile. Since the bike is a simple machine, relying on muscle-power rather than internal combustion, it is easy to conclude that the bike is a more primitive creation. In reality, bicycles represent a healthy relationship between humans and technology. A bicycle is meant for tasks involving little cargo, a common-use case in cities. The choice is between two different sorts of modernity: dense cities for bicycles, or urban sprawl for cars. Before we can understand these possibilities, let’s explore how the bicycle literally paved the way for the dominance of the automobile.

Surprisingly, for such a simple machine, the modern bicycle wasn’t invented until the late 1800s. Jason Crawford at Roots of Progress questions how such a seemingly intuitive device could take so long to create. Crawford describes the bicycle as a product of industrial modernity, even though primitive designs date back to the Renaissance. The bicycle — from the geometrical steel tubing to the finely tuned derailleurs, is a sibling of early motorcars. “The key insight [in creating the bicycle] was to stop trying to build a mechanical carriage, and instead build something more like a mechanical horse,” Crawford writes.

If the bicycle was a mechanical horse, then the motorcar was a mechanical horse-drawn carriage. In fact, the first car was basically a quadricycle with an internal combustion engine. The first gas-powered automobile (the Benz Patent-Motorwagen) was built in 1885 by Karl Benz — a cyclist — with the help of James Starley. Other than the engine, it was built primarily using cutting-edge bicycle technology: spoked tricycle wheels with rubber tires and a bicycle chain.

Even though the first cars incorporated elements from older bicycles like the penny-farthing, the first recognizable modern bicycle, Starley’s “safety bicycle,” was fully created in 1888, three years after Benz’s Motorwagen.

A fact that’s not mentioned enough is that both the bicycle and the automobile came about during the same time period — they are both triumphs of human innovation in the 1880s. The automobile is complex, while the bicycle is simple. The bicycle can carry out the functions of a horse, and a car can carry out the functions of a carriage.

The car has obvious advantages. For instance, a person cannot transport tons of cargo across America on a bicycle. But most humans do not need to drive trucks cross-country. Consider Dutch cities where cars still play an integral role in logistics and shipping, but most people choose the bicycle for everyday activities like commuting or shopping.

“Car cities” like Los Angeles are completely shaped by the needs of car transportation and suffer for it. L.A. has reached an equilibrium built around the car, while many European cities have opted for an equilibrium centered on the bicycle. Cities such as Amsterdam are not economically diminished because they lack numerous multi-lane highways — and their residents are spared the need to pilot an industrial appliance just to run errands. Therefore, the life of a person in a Dutch city is much more “human scaled.”

The question is: how and why did the car beat out the bicycle in so many cities around the world?

Some cities are car cities; others are bike cities. But, as different solutions to different problems, there is a need for both modes of transportation in all cities.

Car cities, bike cities and technological lock-in

In most North American cities, infrastructure and lifestyles are built around the car: why is that? In large part the answer is roads — early cyclists wanted paved roads to ride on, not cobblestone or dirt. The story of paved roads in America is the story of the bicycle, NOT the car. Believe it or not, paved roads were originally created for cyclists.

Bicycles in the late 19th century were luxury goods. They were primarily owned and operated by wealthy people across America who would often form cycling clubs. One of the primary functions of these clubs was to advocate for cyclist’s interests. Cyclists were very interested in riding on roads that were paved, rather than roads made of dirt or gravel (mountain bikes were yet to be invented).

The Good Roads Movement was officially founded in 1880 with the League of American Wheelmen (an organization that is known today as The League of American Bicyclists). As some of the first road lobbyists, they produced a magazine, held conventions and demonstrations, and successfully encouraged the government to build paved roads. The League was a proponent for bicycles when they still looked like the penny-farthing and there was no Interstate Highway System.

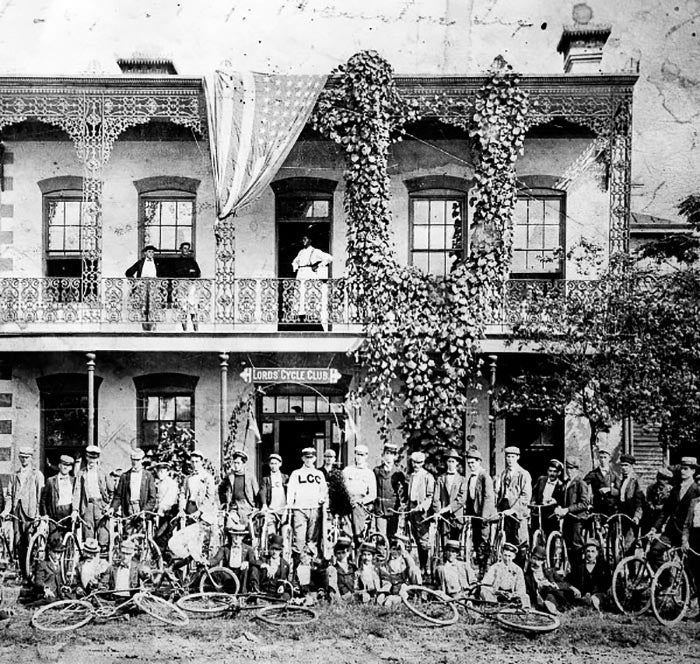

Cycling clubs were very popular in the late 19th century. This photo shows members of the Lord’s Cycle Club of Houston in front of their headquarters on Chenevert Street in 1897.

Photo source: University of Houston Digital Library / Wikimedia Commons

That all changed with the mass production of Henry Ford’s Model T. From 1913 to 1927, more than 15 million Model T’s were produced, making the automobile an affordable luxury item for the first time. As the price of the automobile dropped, the number of motorists increased and roads became filled with automobiles. Drivers co-opted the infrastructure that was created for cyclists and became the dominant group of road users. With the proliferation of inexpensive cars, two-lane roads gave way to multi-lane highway systems that were accessible only to fast-moving cars.

American society became — and continues to be — so entrenched in the technology of the automobile that switching to another is made extremely difficult. It’s what is known as “technological lock-in.” This is the predicament in which most U.S. cities find themselves. The car, originally a luxury good, became a necessity for many Americans, while the low-cost and “antiquated” technology of the bicycle fell into disuse. Cities in America look the way they do because they’re locked in to a technology that is not scaled for human transportation; if they sometimes seem inhuman, it’s because they’re built for cars.

The double symbol of the bicycle

National transportation networks, such as the Interstate Highway System, are extremely useful and make it possible to move people and goods over long distances in a short amount of time. For urban transportation, however, it is important that people use a vehicle that is correctly scaled for their needs. Transporting people (not freight) throughout urban areas shouldn’t necessarily involve a car. There should be space for people to use methods of transportation that reflect the need of the particular trip they are taking.

In many Dutch towns, even a trip to the grocery store doesn’t warrant using a car. Unfortunately, once a city is built at the scale of the automobile, it becomes harder to encourage other modes of transportation, such as bikes, and much easier to further encourage the use of cars. Induced demand is the concept that “if you build it, they will come” — any attempt to improve car congestion by building more highways only increases the congestion in the long run (by encouraging more car transportation). Luckily, this concept also applies to bicycling infrastructure, and cities can encourage cycling by building more bike paths.

Buffalo Bayou Park is one of the most popular parks in Houston.

What the bicycle represents is a human-scale mode of transportation — it goes hand-in-hand with human-scale neighborhoods and communities. The bicycle is a simple and elegant machine: it makes use of basic gear ratios to provide a mechanical advantage to the rider. The bicycle is the fastest human-powered land vehicle, and it can be repaired by anyone with a rudimentary grasp of mechanics; no tinkering with internal combustion engines is required. Bicycles not only benefit riders, they benefit the local and global environment as well; therefore, cities should make it easier to bike, not difficult and dangerous.

So, is it too late for bicycles to be a daily part of life in America?

No.

Bicycles have seen a dramatic surge in popularity in the COVID era. Cities across America are experiencing drastic increases in ridership. In Houston, bike paths are bursting at the seams, a dangerous state of affairs during a pandemic. Not only is trail usage at an all-time high, the Houston bikeshare program (BCycle) has seen record-setting ridership, and bike stores across the area can’t keep inventory in stock. All of which are clear indicators that Houstonians want — and need — more bicycling infrastructure.

What we need is more investment in bicycle infrastructure.

Houston has some beautiful bayou trails, but they don’t have all the connections they need. Bike lanes planned for some of the major thoroughfares in the city (such as lower Westheimer) have yet to materialize. Furthermore, there’s a real need for bike trails in parks — cyclists in Memorial Park don’t like riding with cars, and joggers don’t like running with cyclists. These aren’t expensive infrastructure projects; and currently, the demand is far exceeding supply.

The popular narrative of bike versus car is wrong. In reality, the world is much more nuanced, and a place where both pieces of technology have their uses. Houstonians want to use their bikes, and we need to make it possible for them to do so safely. That doesn’t mean eliminating the car, it just means making space for bikes. Building cycling infrastructure is part of building a city where people want to work, live and visit, rather than just drive through.

Matthew Southey is communications director for BikeHouston.