It’s been a long time coming for transit-oriented development in Houston, and this may be one of the more promising (yet underappreciated) ways to catalyze efforts to reach broader equity, resilience, and sustainability goals.

In 2015, Metro examined the potential for transit-oriented development, or TOD, across its light rail corridors and park-and-ride facilities. But the implementation of the New Bus Network, high-profile capital projects like the Uptown Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), and embarking on a revisit of its long-range MetroNext plan had made TOD discussions an afterthought.

Since the TOD study was unveiled, many issues have been competing for urgent attention on the urban stage — repeat natural disasters, a global pandemic, and an affordable housing shortage for low-income Houstonians, among others. Policy discussions have shifted in light of the new awareness of these issues.

Now the agency seems poised to play a more prominent role in meeting some of these challenges by collaborating with public, private, and nonprofit partners to create walkable, mixed-use communities, expanding the reach of public transit and making it easier for people to build their lives around walkable communities with multiple transportation options—not just the car.

What is TOD and how does it help Metro?

TOD refers to any development within a 10-minute walk (or a half-mile) of a high-frequency transit station or stop. It is primarily characterized by compact, mixed-use development near rail or bus facilities and can be a mix of land uses, such as residential, commercial, office, retail, and civic uses.

Too often, transit stations/stops have a notable absence of development nearby. Which is precisely where Houston stands now. Most of the transit stations, except for the MetroRail’s Red Line, have a noticeable absence of TOD. That is not the case in many other peer cities in the U.S., and it's largely prompted by the fact that the transit agencies themselves are spurring TOD, primarily through a practice known as joint development.

Joint development involves real estate owned by a transit agency, which partners with public and private entities to build walkable development on the site. It is the most valuable tool that transit agencies have to promote TOD at rail or bus facilities.

The agency’s goals now seem to go much further than simply financial objectives, subject to Federal Transit Administration (FTA) sign-off (i.e., improving the customer experience, enhancing the value of Metro assets, promoting equitable TOD, leveraging resources and funding, and advancing multisector partnerships). It is essential to not downplay the significance of Metro’s newfound holistic approach to TOD. But, as FTA recognizes, the impact of public finance tools in TOD should not be overlooked for how powerful they might be in helping the agency deliver a more equitable transit system overall, particularly land value capture and revenue generation strategies.

The Bay Area's Fruitvale Station includes mixed-use transit-oriented development with apartments and retail. (Wikimedia Commons)

Land value capture, or LVC, allows communities to recover and reinvest increases in land value that result from public investment, in this case, transit infrastructure investments. Research has shown that transit investments increase land values by 30 to 40% within a few short years. Transit agencies routinely acquire land for rights-of-way and station needs. Now, the agency’s acquisition goals might be more expansive as it looks to help stimulate transit-oriented development. Metro and partners would be able to capture some of the gains in land values and leverage these gains to finance transit capital projects or pay down debt used for infrastructure. Other public finance mechanisms, such as TIRZs or special assessment districts can also be used to capture part of the incremental increase in tax revenue generated by rising property values resulting from TOD investments. Coordination with the city’s economic development office is vital to ensure Metro can access its fair share of LVC from transit-induced increases in coordination with existing TIRZs. Examples of this model include London’s Crossrail 2 station or NYC’s Hudson Yards.

Revenue generation is a form of LVC and usually occurs when a transit authority retains ownership of its real estate and leases land near stations to developers who can build development as envisioned by the transit authority and its partners. While the development might have the look and feel of a private mixed-use project, it would generate returns for the transit agency for up to 99 years. One noteworthy example of this is in Copenhagen, where redevelopment of its North Harbor generated nearly $6 billion used to construct the city’s ring line. Furthermore, these long-term revenue streams may open up new public financing tools, specifically revenue bonds, which are determined by the volume of an agency’s collateral, in this case, long-term rents across its joint development portfolio. In effect, joint development is another way to advance the MetroNext plan and deliver the transit vision that was endorsed by a majority of Houstonians in the 2019 bond election.

How can TOD help with equity, resilience, and sustainability goals?

Tapping into the public finance benefits of real estate is not simply about making money for the transit authority. Leveraging these innovative funding sources improves equity, as it will translate into more transit-supportive infrastructure, improved service, and affordable and workforce housing options near Metro facilities. These improvements will directly support lower-income Houstonians, who pay some of the highest transportation costs in the nation because of the region’s auto dependency and who typically do not have the option to live in proximity to frequent transit.

However, the burden should not be entirely on Metro to unilaterally meet regional goals toward equity, resilience, and sustainable development. There are established policy objectives by the city, county, and region, where Metro’s development strategy is a way for the agency to contribute and help deliver win-win partnerships with regional impact.

For example, the city of Houston reformed its TOD standards in 2020 through its Walkable Places program, relaxing parking requirements and setting design standards for the public realm along the high-capacity transit network and designated TOD streets. These reforms ensure that private development around transit infrastructure is walkable and has transit-supportive urban design.

Resilient Houston, the City of Houston’s climate adaptation strategy, has also been a big driver of urban policy. The strategy aims to house 100% of Houstonians within a half-mile of high-frequent public transit by 2050. Today, about 54% of Houstonians live within a half-mile of high-frequent public transit. Metro’s approach is likely to provide more opportunities for Houstonians to live within a half-mile of frequent transit service. But so can the expansion of high-frequent transit service to underserved areas, which can be financed by joint development activity. Moreover, living in proximity to transit is important, but can the 54% of the population living closely actually access the service? A TOD strategy must also examine station access by improving bike/pedestrian connections and design so that people of all ages and abilities can comfortably and conveniently use public transit.

Similarly, the city’s climate action plan has a goal to reduce annual VMT by 20% by 2050, but it's actually trending in the opposite direction with an 18% increase since 2020 (despite the pandemic and more work from home). Houstonians are simply driving more, and that is perpetuating harm to our air quality, Vision Zero and traffic safety efforts, and affordability challenges. TOD and joint development can bring more compact, mixed-use development near people’s homes. This won’t eradicate driving altogether, but many vehicle trips per household can be reduced (and thus VMT) by having more diverse land uses near people’s homes, such as essential services and retail, office space, or parks and public space. TOD creates sustainable alternatives to driving.

These are brief examples of how TOD can support equity, resilience, and sustainability. But the possibilities are endless if development were to take off near transit. With robust public engagement and supportive partnerships, TOD can help revitalize neighborhoods and address longstanding inequities, such as park or food deserts, through thoughtful design of public space or a tailored commercial revitalization strategy. TOD could also provide more family support services in affordable housing developments—English language and computer classes, personal finance, and childcare facilities—such as Austin’s Station M example at MLK Station which meets the city’s S.M.A.R.T. Housing Policy Initiative (Safe, Mixed-Income, Accessible, Reasonably Priced, and Transit-Oriented).

Metro’s stakeholder engagement and the expansion of its development efforts are an invitation for creative and innovative approaches like this to deal with multifaceted challenges, specifically around housing investments, an area of growing need.

TOD and the critical need for more housing

The area’s housing affordability challenges have gained notoriety in recent years. There is a housing shortage of nearly 160,000 homes for low-income households (those earning less than 30% of AMI) in Harris County. This leads to immense competition for affordable units in both low-income and workforce populations (up to 80% AMI). It is one important reason why more than half of all renters are cost-burdened, meaning they pay more than 30% of their income on housing, and why Harris County is a national leader in evictions and leads many families to be housing insecure.

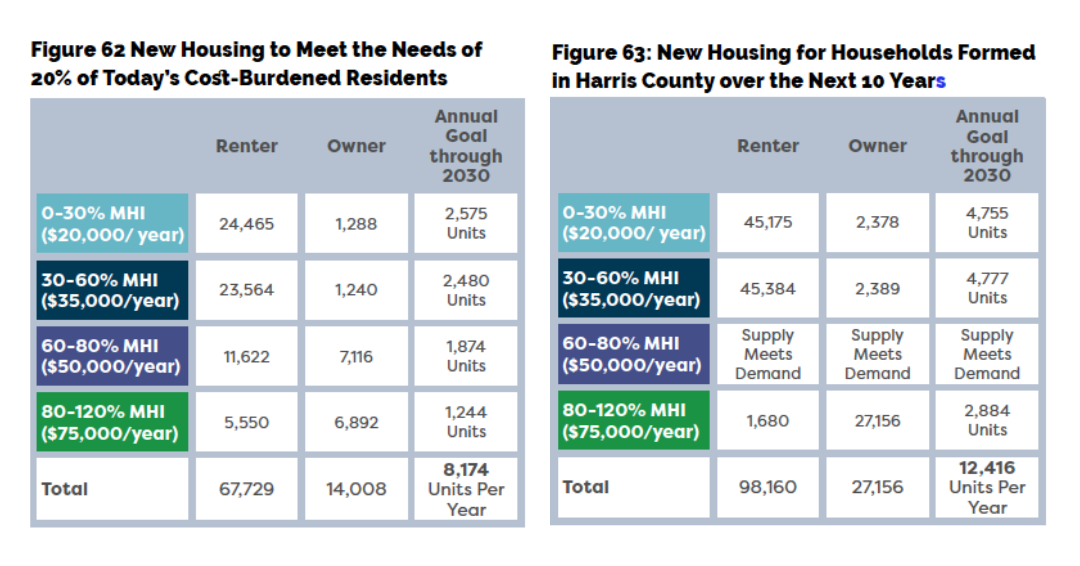

Harris County needs a combined 200,000 units of housing built over the next 20 years to meet the needs of new households and cost-burdened households. (Source: My Home is Here)

To address the housing crisis, Harris County’s Community Services Department carried out an award-winning plan with a targeted investment strategy to build 200,000 more housing units (or 20,000 per year) over the next decade. Getting support from public sector partners, especially those who own land, can go a long way to pair with investments from real estate developers, philanthropy, and the nonprofit sector.

Metro’s land holdings offer a glimmer of hope toward that end. Based on the average dimensions of the agency’s 26 existing park-and-ride facilities and 21 transit centers, a conservative estimate suggests as many as 50,000 dwelling units could be developed if all sites were built out at mixed-use density levels—100 units per acre on park-and-ride facilities and 150 units per acre on transit center properties, not including corridor stations on BRT/LRT lines, new property acquisitions and adjacent land holdings. This would translate to 25% of the county’s housing goal, creating new housing options in transit-rich, walkable communities, but even half that amount, 25,000 units or 12.5% of the goal, would be a laudable contribution toward housing equity.

In short, TOD’s moment is now. Metro is opening up new possibilities to create compact and connected, walkable places, which can be a big boon to equity, resilience, and sustainable development initiatives across the Houston metropolitan area. These new transit villages can forge a different development form and change the trajectory of how this city is built. But the extent of what occurs and the places we create is up to all of us.