Editor’s note: This is the second post in a four-part series on the Kinder Institute for Urban Research’s new report, “Re-Taking Stock: Understanding the Connections between Housing Trends and Gentrification in Harris County.” The report connects housing stock changes with gentrification risk in Harris County.

As demand for homes has soared during the COVID-19 pandemic, cities across the United States are experiencing record housing shortages. Prices in already expensive markets have skyrocketed, with homes selling within hours of listing. The home-buying frenzy would appear counter-intuitive to many because it’s occurring during an economic downturn of historic proportions.

Surprisingly, news and media outlets are mainstreaming the problem’s wonky underlying causes — known as the five L’s (labor, lots, lumber, lending and land-use laws). The Urban Institute recently tested these five L’s through a statistical analysis and found that, of all five, land constraints are the most important factor driving the pandemic housing shortage. And, quite remarkably, even President Joe Biden has chimed in, claiming, “restrictive zoning laws — like minimum lot sizes, mandatory parking requirements and prohibitions on multifamily housing — have inflated housing and construction costs and locked families out of areas with more opportunities.”

But to many in housing and land-use planning, this supply crisis is neither new nor a surprise. Urban planning scholars have long studied the disastrous effects of low-density urbanization on racial segregation and environmental degradation, and have noted that housing production in American cities has been a growing challenge because of restrictive land-use policies that favor single-family zoning and perpetuate a ‘chain of exclusion.’

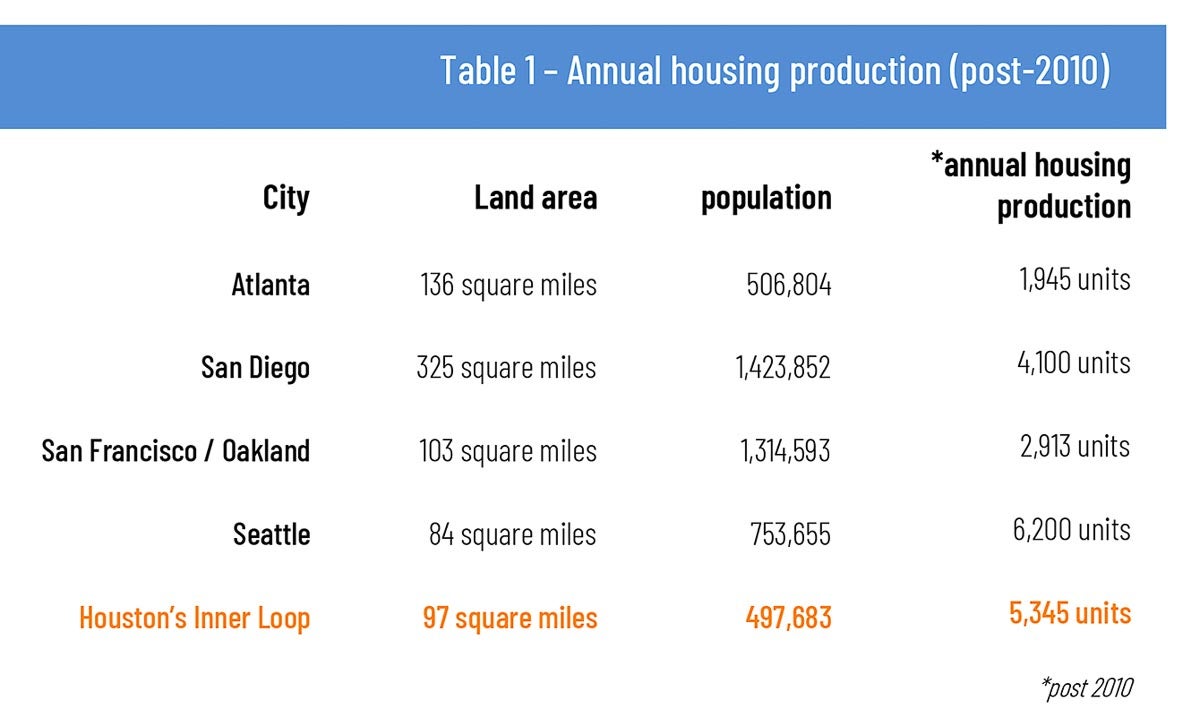

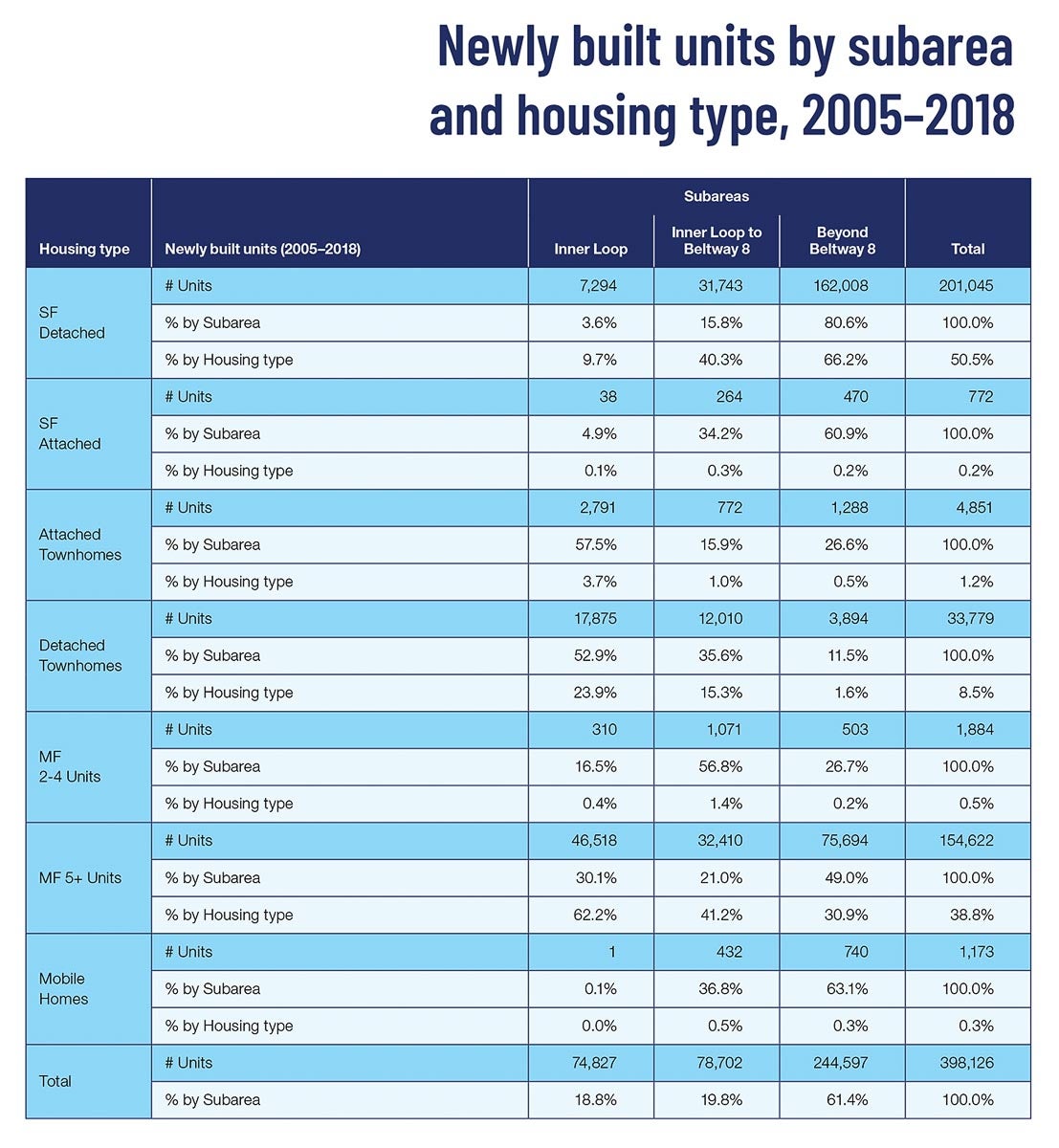

Research recently published by the Kinder Institute sheds light on the ways in which two of the five L’s — laws and lots — have reshaped housing development in Houston since 2005. We observed a steady uptick in more land-efficient, compact housing development in the city’s urban core (i.e., Inner Loop) near Downtown — most notably in the growth of small-lot townhomes. In fact, over the past decade, annual housing development just within the 610 Loop (which accounts for about 15% of the Houston’s total land area) surpassed the total annual housing production of other major cities (Table 1), including the annual housing production of Atlanta, San Diego and San Francisco/Oakland, and approaching that of Seattle’s.

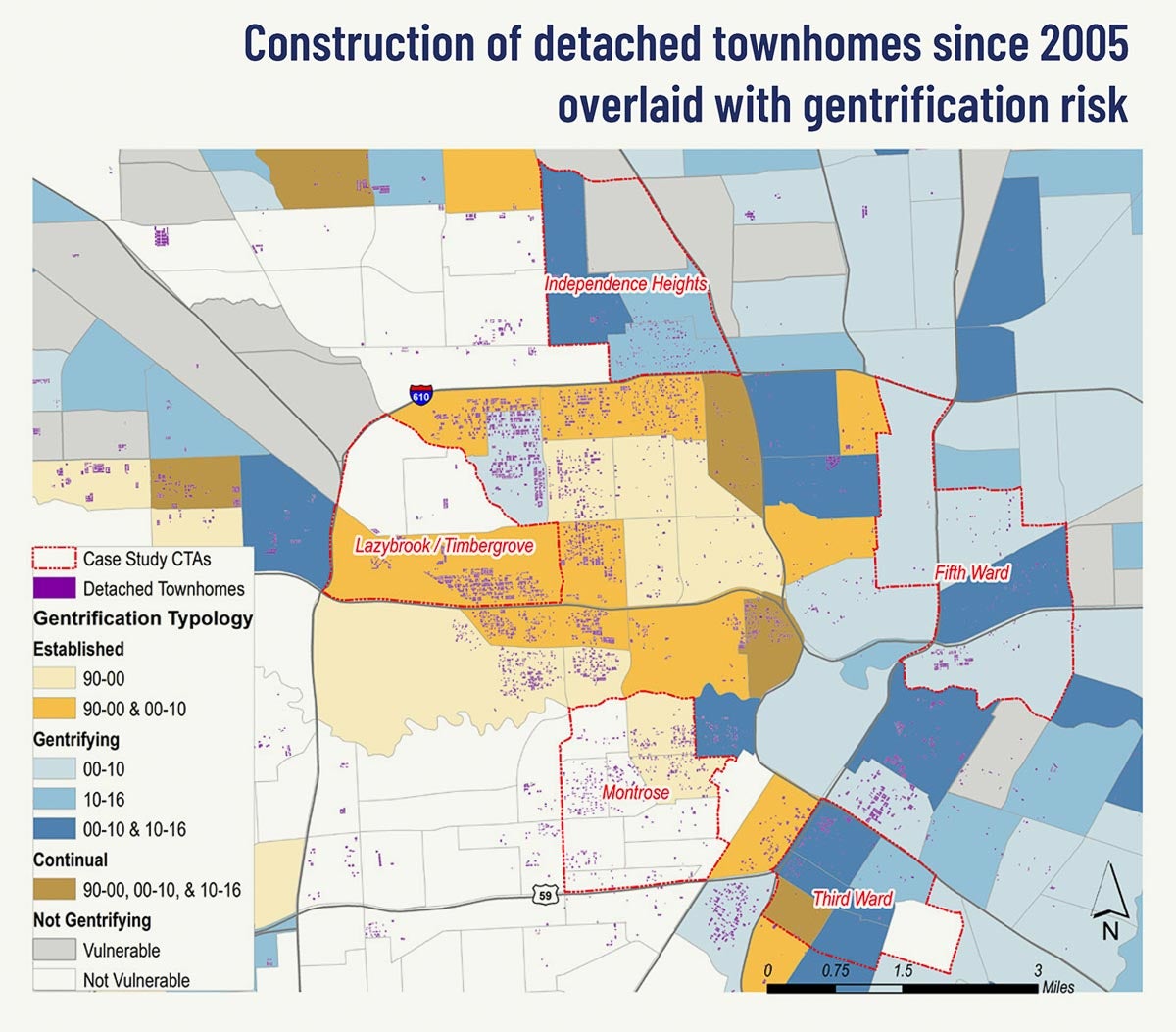

In addition, we found that most of this dense housing growth occurred most rapidly in high-demand areas with low gentrification risk (to our surprise) and hypothesize it is likely the result of Houston’s reduced minimum-lot-size requirements and lack of use-based zoning. The latter is rare in American cities, where low-density, single-family zoning has proven difficult to up-zone into more climate-friendly housing — which inevitably increases demand for more urban living and, in turn, gentrification in lower-income communities of color.

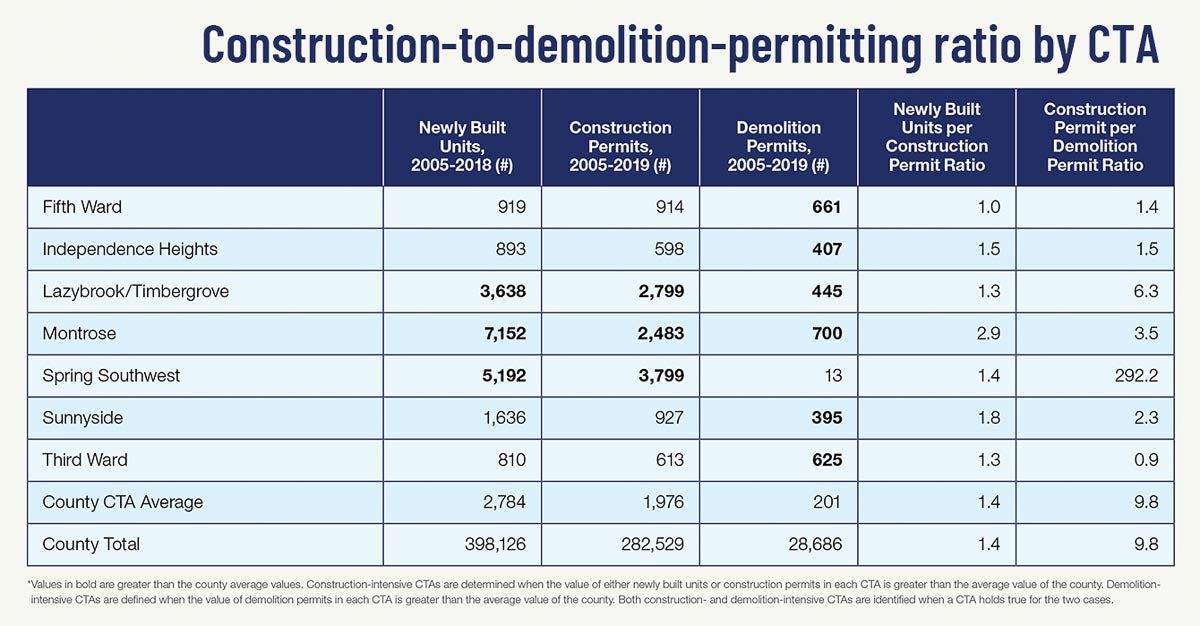

Gentrifying CTAs: Fifth Ward, Independence Heights, Sunnyside and Third Ward

High-Demand CTAs: Lazybrook/Timbergrove and Montrose

Inner-Suburban: Spring-Southwest: This is an outlier in its construction-permit-to-demolition-permit ratio because of the sheer size of the CTA and growth of housing on previously undeveloped land

What is a townhome in Houston and how does it fit into the picture?

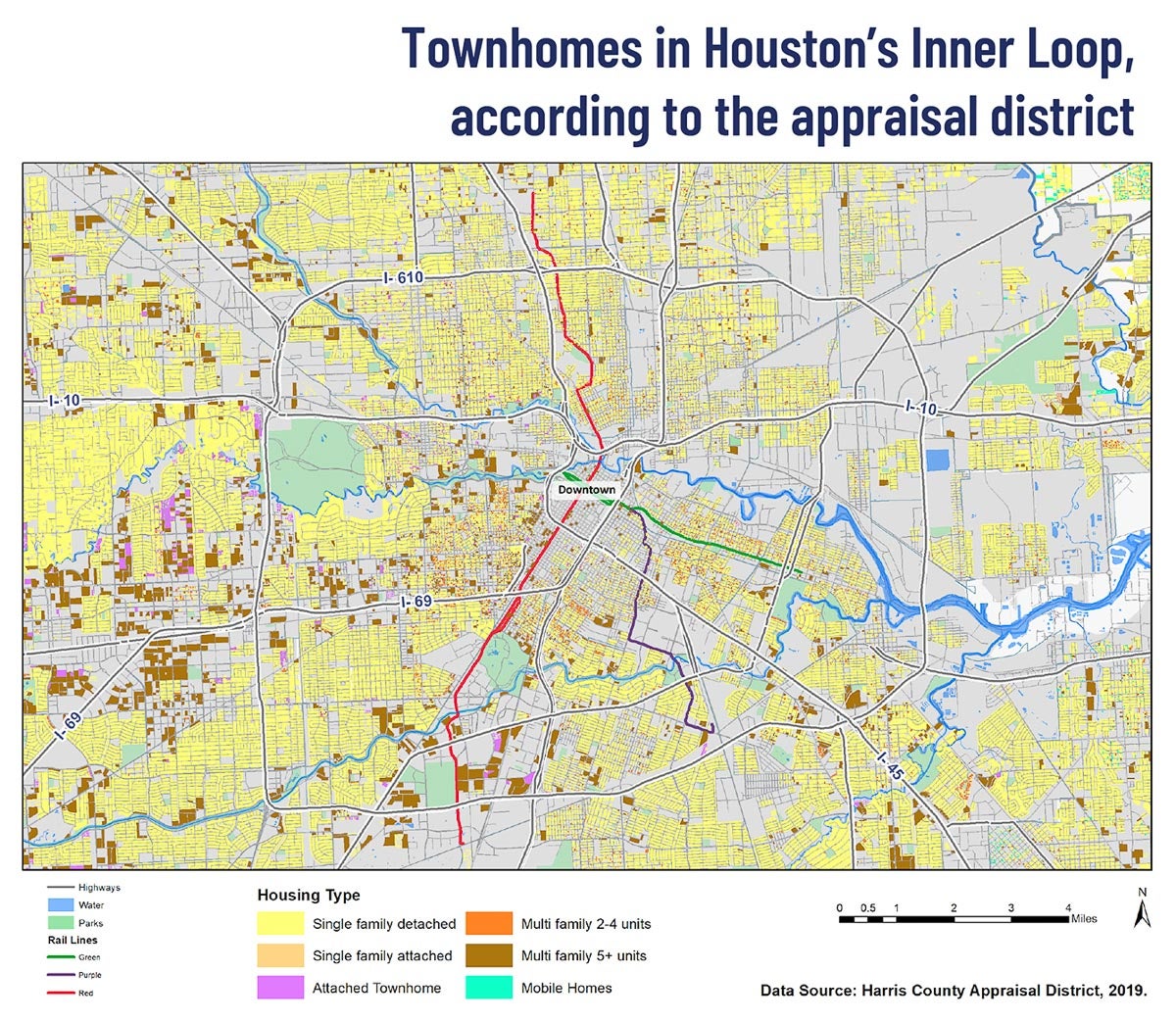

First off, it’s important to clarify what we mean by “townhome” in this analysis. Kinder Institute senior research fellow John Park, Ph.D., AICP, and I wanted to learn how we could identify the rapid growth of small-lot homes (lots less than 5,000 square feet) using Harris County Appraisal District (HCAD) records. These small-lot homes, which were legally permitted after Houston reduced its minimum-lot-size requirements in the late 1990s, often are overlooked in mapping analyses because they’re classified as “single-family” homes in appraisal district records.

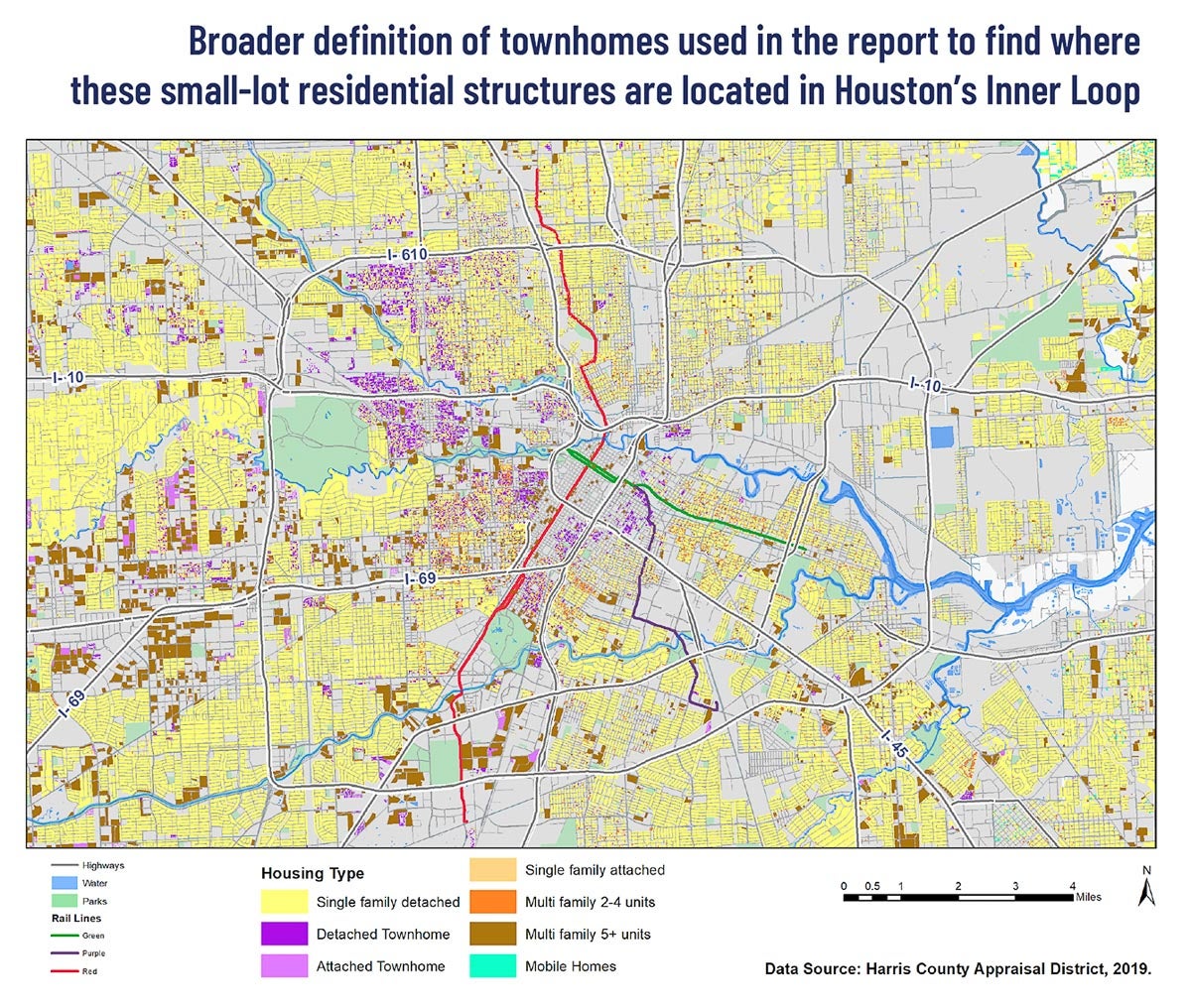

We realized it would be misleading to include this housing type along with traditional large-lot, single-family homes. The appraisal district strictly defines “townhomes” as being physically attached to neighboring units; however, a large number of free-standing townhome-like structures (3-plus stories and separated by a few feet) have been built on lots smaller than 5,000 square feet. Structurally, these homes are more similar to what is commonly associated with townhomes in Houston’s vernacular than with single-family homes. Therefore, to differentiate the two, we opted to define this free-standing small-lot housing type as a “detached townhome” and added “attached” to the appraisal district’s original townhome label. (See map below for differences in mapping result.)

Both the conventional definition (attached townhome structures) and detached townhome are included when the word “townhome” is used in our report, though we isolate “detached townhome” when the focus is isolating the impact of Houston’s reduced minimum lot size.

Houston’s surge in compact townhome development

Despite townhomes accounting for only 4.7% of the city’s entire housing stock, they made up nearly 10% of all newly built housing units in the city since 2005, and more than 27% (20,666) of all newly built housing units in the Inner Loop during that time. Detached townhomes comprised nearly 18,000 of those units, emerging as the predominant townhome structure being built in Houston, which is why they merited attention in this report.

In 2007, the city extended the reach of its reduced minimum-lot-size requirement beyond the Inner Loop. Since then, an additional 15,800 newly built detached townhome units have come online outside of the 610 Loop.

Inequities of redevelopment

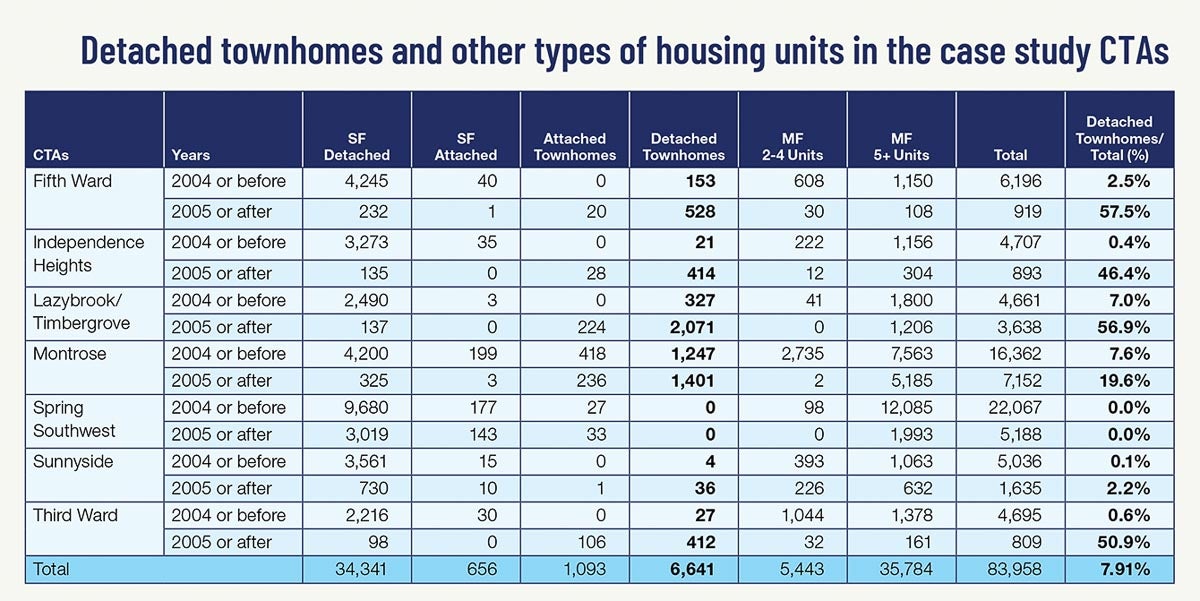

Detached townhomes account for about half of all newly built units in the gentrifying areas of Houston. They appear to be speeding sociodemographic shifts and threatening housing affordability in at-risk communities, particularly in Fifth Ward, Independence Heights and Third Ward (Sunnyside is the only exception of the case-study neighborhoods we examined; more on that below). This is driven by the fact that townhomes are associated with attainable costs for families earning closer to 160% of the area’s median income, attracting high-income households of young adults to neighborhoods where many lower-income people of color live, which poses a threat to the housing stability of the latter.

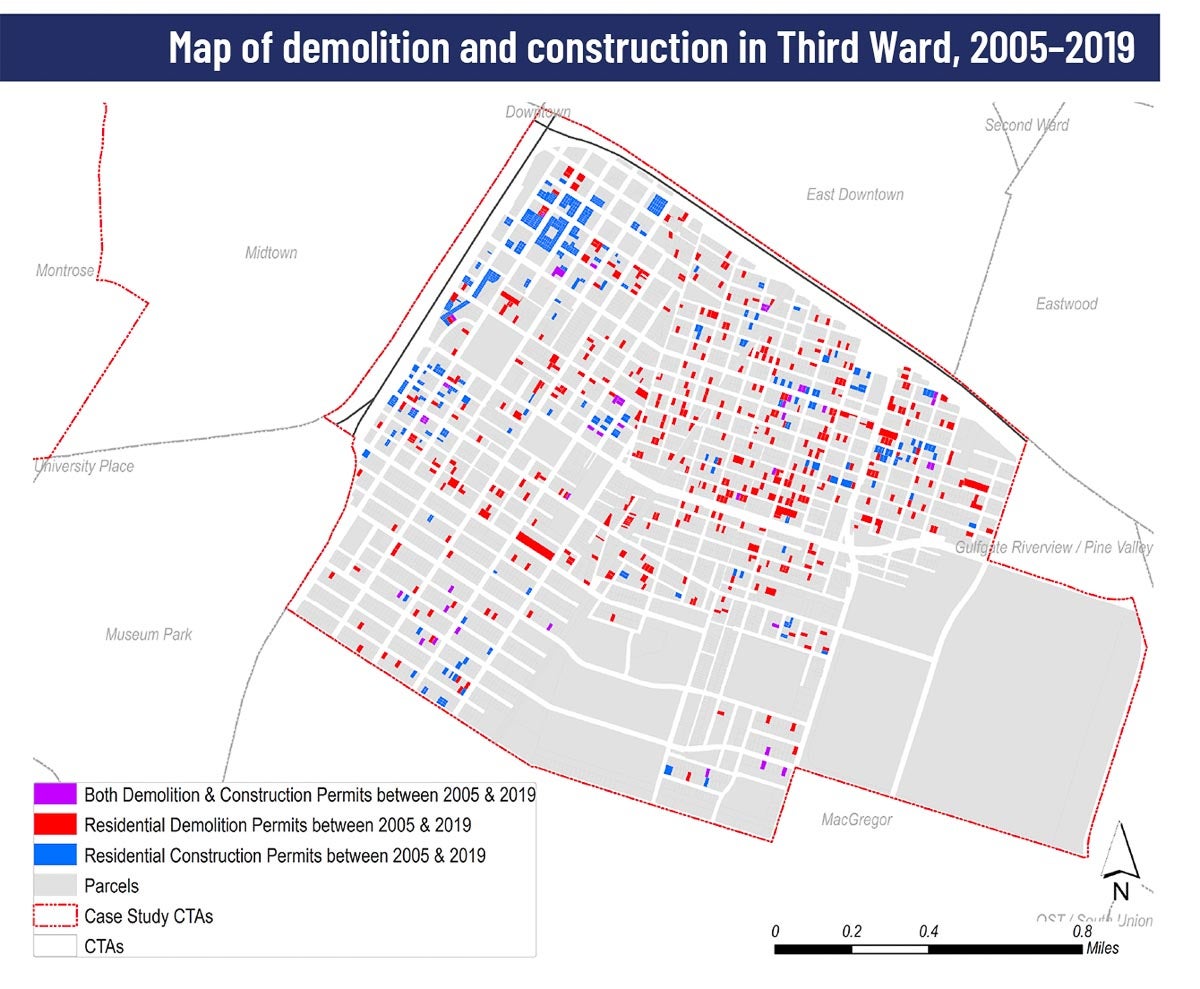

But it’s not only the construction of townhomes that is impacting neighborhood demographics — demolitions are rampant in gentrifying neighborhoods, and are displacing residents long before redevelopment occurs. This would seem to suggest that discussions about housing preservation and affordability need to begin much earlier than when townhome development begins on subdivided lots where older single-family housing once stood.

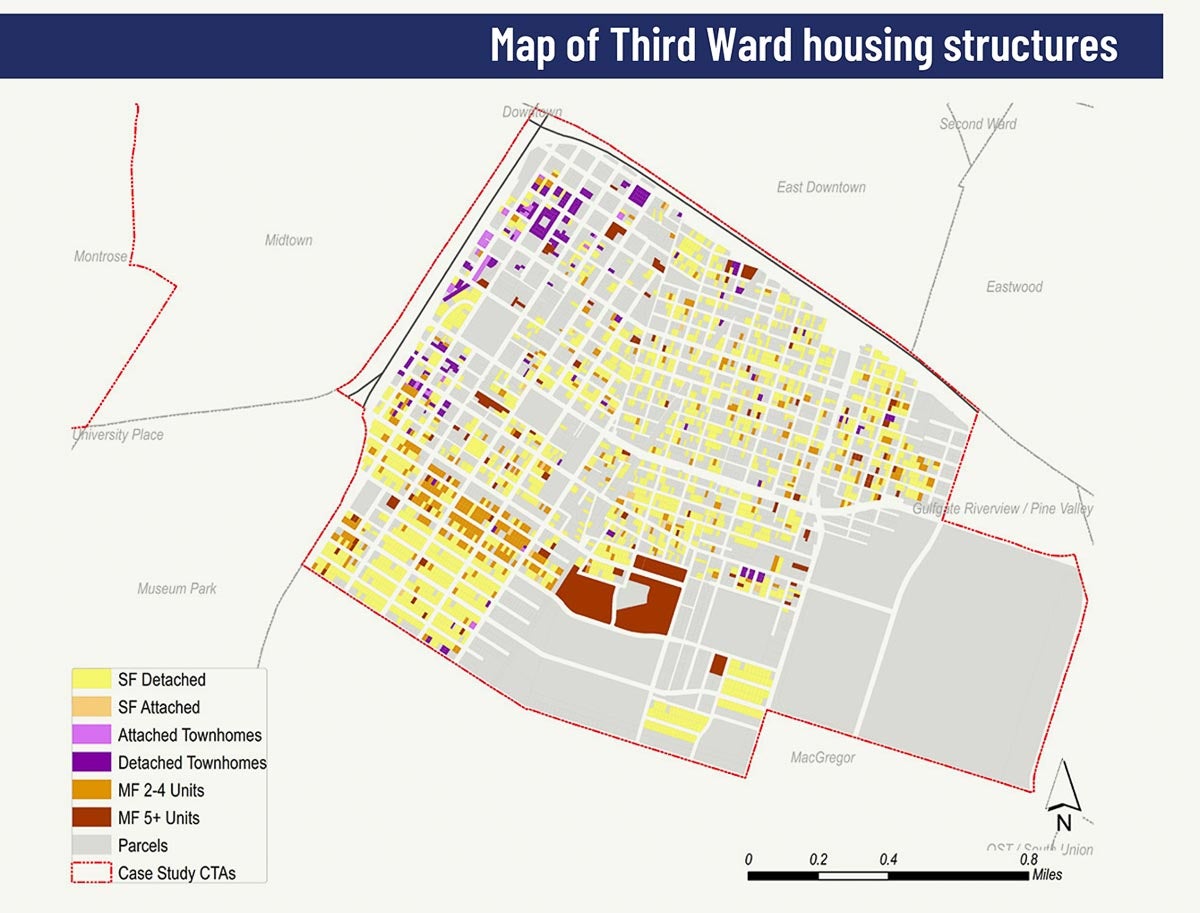

For example, these Third Ward maps illustrate the phenomenon at the neighborhood level. The first shows how parcels that experienced both demolition and construction from 2005–2019 are primarily fixed on the western boundary of the neighborhood, next to Midtown, an area that gentrified in the 1990s. It is clear from the second map that most of those parcels also happen to be detached townhomes (in purple). The scale of detached townhomes in Third Ward is eclipsed, however, when we compare parcels that were permitted for demolition between 2005 and 2019 (red on the first map).

Gentrifying neighborhoods like Third Ward can benefit greatly from more robustly funded housing preservation and affordability interventions that support the preservation efforts and ensure that redevelopment is aligned with the community’s goals in expanding affordable housing for area residents.

Opportunity to bring more housing diversity to Houston and address blind spots of townhomes

The city is currently working on an initiative to expand “missing middle” housing types, dubbed Livable Places (full disclosure, I am a committee member). The committee’s central objective is to “focus on updating its development code to encourage the development and preservation of affordable, quality housing for all. It will also focus on creating opportunities for increased infill development that will strengthen Houston’s core, encourage use of multi-modal transportation options, improve safety, and preserve great neighborhoods.”

Finding ways to incentivize more diverse housing options could be a boon to counter the high share of costlier townhomes, including the expansion of multiplexes, accessory dwelling units (aka granny flats) and other missing middle housing options. The Livable Places committee is also tasked with evaluating how urban design and transportation coalesce around new housing development standards. This might prove helpful in avoiding the incursion of “slot homes,” and by introducing more human-scale design to the public realm for enhanced walkability and street safety. That’s because many townhome developments either face inward, with a shared driveway down the center, or the pedestrian realm is dominated by vehicular access.

Promising signs in Sunnyside point the way

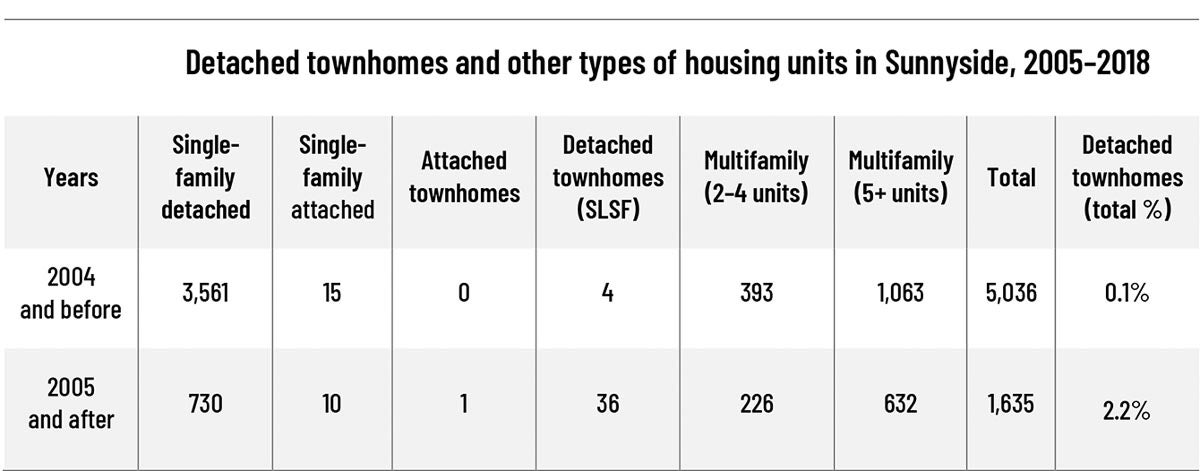

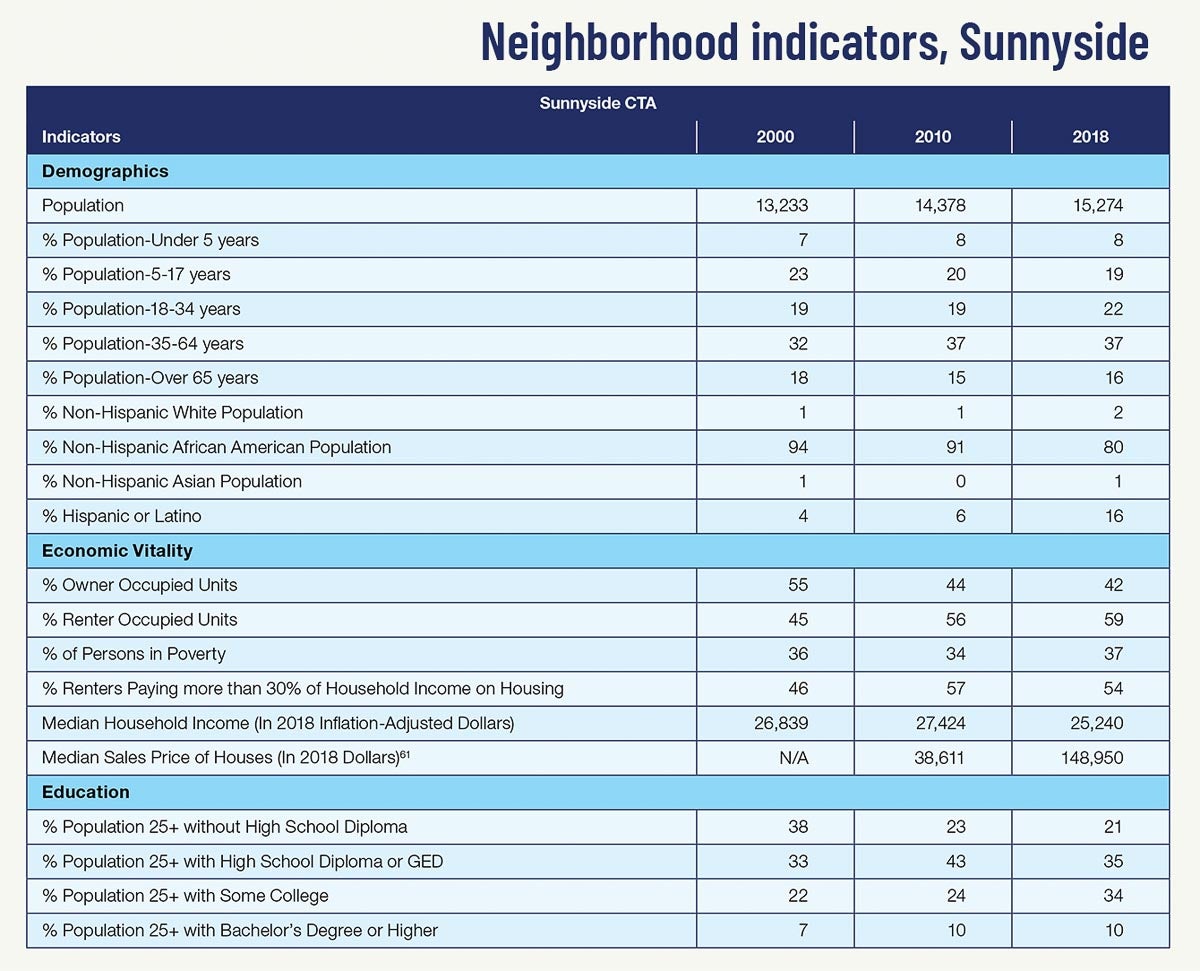

Townhomes were noticeably absent as a built housing type in Sunnyside — a stark difference compared to other gentrifying case-study neighborhoods such as Fifth Ward, Independence Heights and Third Ward. With their proximity to downtown and adjacency to high-demand neighborhoods, those gentrifying neighborhoods are placed under additional pressure that Sunnyside does not face to the same extent. However, the rise of “missing middle” housing and the renovation of single-family homes are promising signs for community developers in Sunnyside.

For example, we found that one-third of all new multi-family development in Sunnyside was small multi-family units (two to four units). Also referred to as multiplex developments, they are a vital part of the “missing middle” housing type that’s needed. This housing type predominantly was built in Sunnyside’s central census tract, where gentrification occurred between 2000 and 2010, and much of those units were built after 2005. Sunnyside is the only case-study neighborhood in which this housing type increased.

Demographic shifts in Sunnyside have not been as abrupt as those in other gentrifying neighborhoods where demolitions and townhomes were much more prevalent. Despite the federal and local governments locking horns in the 2010s over the use of disaster recovery monies to further fair housing and undo decades of racial segregation, community developers in Sunnyside were successful in securing disaster recovery funds following Hurricane Ike to renovate a number of single-family homes, many of which were converted into small multifamily units such as duplexes and triplexes.

Redevelopment trends in Houston support the argument that relaxed land-use regulations (i.e., lack of use-based zoning and reduced requirements for minimum lot size) can lead to the development of more housing units near major job centers, services and transportation choices. It is also evident that more needs to be studied to address gentrification earlier in the process, and assess how other “missing middle” housing types might support more affordably priced housing for low-income families.