The significance and promise of education in America is empowering. For a Black child, it can be life-changing. Yet, in 21st-century America, the promise of a Black child receiving a quality education is not assured.

It was more than half a century ago that the Coleman report (Equality of Educational Opportunity) — a groundbreaking 737-page study named for sociologist James Coleman and considered the most important educational study of the 20th century — suggested that Black children learn better in integrated schools. It was a conclusion that would help put in motion the mass busing of students to help achieve racial balance in U.S. public schools.

“The great majority of American children attend schools that are largely segregated—that is, where almost all of their fellow students are of the same racial background as they are. Among minority groups, Negroes are by far the most segregated. Taking all groups, however, white children are most segregated.” — Equality of Educational Opportunity, (1966)

The Coleman Report, conducted in response to Section 402 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, was a comprehensive report that did not include any recommendations on the policies or programs that federal, state or local government agencies should enact in order to improve educational opportunity.

In the more than five decades since Coleman and his colleagues’ first documented racial gaps in student achievement, education researchers have debated the reasons why these gaps persist and have put forth recommended solutions. Today, many schools in the U.S. remain segregated.

Racism is an insidious disease, which permeates society in every aspect. Segregation benefits no one and robs all of us.

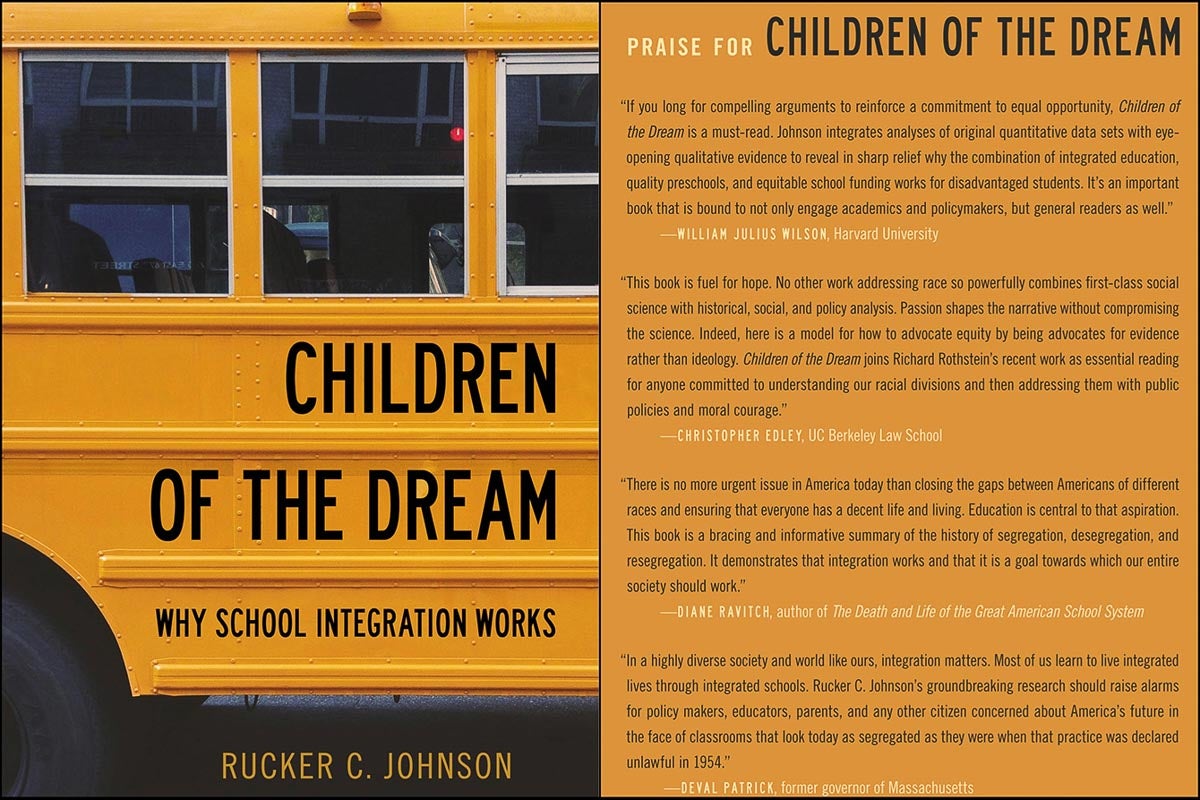

In his latest book, “Children of the Dream,” Rucker C. Johnson, a leading mind on the economics of education, contends that school integration efforts in the 1970s and ‘80s were overwhelmingly successful. And using longitudinal data, Johnson shows that students who attended integrated and well-funded schools were more successful in life than those who did not — and that this benefited children of all races.

“Children of the Dream” is a must-read on the rethinking and reshaping of integration, and what its absence means for our education system, our children and our society. Given the current racial climate and the historical context of race woven throughout the book, I welcomed the opportunity to speak with Johnson.

(The following conversation has been edited for length.)

Q: What was your inspiration for writing “Children of the Dream”?

A: My book was borne out of my research — out of my passion for the economics of education and my desire to speak to a broader audience about what I have discovered through years of research: school quality and school spending matter, but school integration is also a necessary component of a strong, effective school system that benefits all children. I also wanted to show the human side of data — to uplift the untold stories of our school-desegregation heroes.

My book was written for this moment in our nation, and so many before it in which these issues have been neglected. Now is the time to turn a moment into a movement for social change and racial justice for all.

We must think of racism as an infectious disease; silence leaves the illness untreated. When it is not confronted, it spreads and destroys the health and well-being of our nation.

All segments of our society have difficulty with race and some discomfort with discussions regarding structural racism. However, an essential part of the policy prescription for change must include school integration where students and teachers learn and transmit the power and value of diversity. These students often go on to work in certain occupations that must have a higher standard of accountability and there is no margin of error without dire and life-threatening consequences for specific racial and ethnic groups. These occupations in particular include law enforcement, education and healthcare. In these sectors specifically, we must demand that individuals receive training and develop sensitivity to both implicit and explicit biases — and promote anti-racist views. When racist belief systems are deeply embedded into the culture and the system and DNA of organizations, then the risks of what happened in Minneapolis (George Floyd) are more likely, and we’re seeing this across the nation all too often.

When law enforcement assumes guilt vs. innocence, when educators under-educate or students internalize a culture of low expectations for performance, or health care is not preventative and accessible care, the consequences are tragic and destroy our capacity to achieve equal opportunity.

There is a tendency toward small incremental, fragmented policy solutions to address unequal educational opportunity — instead of comprehensive school finance reforms with transformative power to break the cycle of poverty. There are many barriers to change. One goal of my work is to address one of the primary reasons: misconceptions about the evidence on the impacts of school resources, integration, and pre-K investments on student success.

Q: You dedicate “Children of the Dream” to your dad. What life lessons did he instill in you?

A: The life lessons my dad instilled in me are too many to innumerate here, but one of them that pertains directly to my book was a deep appreciation for the lessons of history and what they can teach us about the way forward.

Too often research and public debates on inequality are ahistorical and have policy amnesia. Both the accumulation of wealth in predominantly white communities and the concentration of poverty in predominantly minority communities has been government assisted. We must not be ahistorical about the long legacy of past policies that helped us get to this point. If policies played a role in creating and exacerbating disparities, then policies must be implicated to address and help solve the legacies of those policies that are still being felt.

Q: In the book, you mention the importance of the role of the teacher in the classroom. What do you remember about your favorite teachers in school and/or in college?

A: I come from three generations of educators. My parents were my first teachers and mentors — as they were life-long educators and exposed me to the power of mentorship. As the product of exceptional mentorship by a number of generous people, I can attest to the critical importance of mentorship at all stages of personal and career development. The ability to see potential at the very early stages of develop and willingness to be instrumental in drawing it out is key.

Now that I serve in a mentorship capacity, I draw on my Dad’s and other mentor’s inspiration, with a keen understanding that while all mentors play a special role in shaping the next generation of scholars — mentors of color play an especially unique role in the lives of scholars of color.

The truly gifted mentors and teachers inspire and are catalysts to the success of their mentees in a way that transcends the boundaries of gender, race/ethnicity or discipline. The mentor's voice echoes in our own far down the road as we join in the responsibility and joy of mentorship. We are better listeners, writers, teachers, and administrators when we are embraced, nurtured, and challenged by our mentors. We become stronger in character and gain clarity and confidence in our research agenda because of our mentors. We learn how to pay it forward by the liberal giving of mentors.

Acclaimed economist Rucker C. Johnson will discuss his new book, “Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works,” at the Kinder Institute’s Urban Reads program on Oct. 29. Register for the webinar here.

Q: What would you suggest school districts do to attract good teachers?

A: As it has been said, “The mediocre teacher tells. The good teacher explains. The superior teacher demonstrates. The great teacher inspires.” — William Arthur Ward

Teacher quality is often the missing ingredient of school resource equity. Teacher racial diversity can be an important part of that quality. Teacher professional development and increased salaries among pre-K and K-12 teachers is important to recruit, develop and retain our best educators in the public school systems across the country.

Rucker C. Johnson’s work considers how poverty and inequality affect the chances for success in life. His latest book is “Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works.”

Q: You make a strong case for desegregation and integration. With many U.S. neighborhoods segregated, and given that most students attend a school in their neighborhood, how are we to integrate schools today or reap the benefits of integration?

A: Because most of segregation today occurs between districts rather than within them, inclusionary housing policies that promote mixed-income communities are essential. As we show, resegregation is not an accident but is intentional and policy-induced — most importantly; it is harming kids’ outcomes.

By analyzing data on children followed into adulthood, I find that the resegregation of public schools has contributed to the increases in racial bias, racial intolerance, and rising polarization of political views that we observe expressed in adulthood. These effects, rooted in a lack of exposure to racial/ethnic diversity in schools, are most pronounced among white Americans. Not only that, but children in these schools struggle to develop the ability to empathize with others, and to appreciate the validity of other cultures. For African Americans, our results show that confinement to segregated, poorly funded schools interferes with children’s life chances.

There are many long-term outcomes of the quality of public schools that must be measured far beyond simple calculations of test scores to gauge learning outcomes; and developing leadership skills and an appreciation for the value of diversity is central among them. If schools are truly to be one of the birthplaces that mold and produce future leaders in government, business, medicine, criminal justice policy, etc. ..., then we must commit to the promotion of integrated schools. When we don’t make such a commitment to these efforts (as we have not recently), we see the risk of tragic outcomes like Minneapolis become more and more frequent.

Moving from desegregation to integration means moving from access to inclusion, from exposure to understanding.

Q: Some people believe that charter schools help expand school choice. However, not all charter schools offer a high-quality education. What are your thoughts on charter schools?

A: School choice without equity guidelines can exacerbate school segregation. The way school choice policy operates in the majority of US metropolitan areas is conditioned by parental wealth, zip code, high-test scores, and race. When people promote the idea of school choice, we must consider the nature of that “choice” for low-income families. It is most often the case that parental wealth is a requirement to effectively exercise choice through residential housing/zoning policies.

As a whole, unregulated charter school growth has been shown to exacerbate school segregation without a proven track record of consistently improving access to high-quality schools for poor and low-income families. Charter schools have often not been required to comply with the same oversight as public schools (e.g., desegregation guidelines). The facts are that state with permissive district secession laws (which spur gerrymandered school district boundaries), and unregulated charter school growth policies, accelerate racial and socioeconomic school segregation patterns. And doing so under the guise of “local control”. But it is often designed to control racial and socioeconomic composition of schools in segregative ways.

We must remain vigilant to address modern-day forms of state-sanctioned discrimination of education opportunities by race and class.

Q: What key points would you like parents, educators and/or policymakers to take away after reading “Children of the Dream”?

A: Systemic problems require systemic solutions:

1. Integration

2. School Resource Equity

3. Access to quality pre-K programs

We are all part of the system, but we all must recommit ourselves to be a part of the solutions.

A just school funding system is one with a progressive funding formula that equitably distributes school resources to ensure the promise of equal educational opportunity can be realized for all children, irrespective of race and zip code. Love for our children and their future is the motive; a just school funding formula is the instrument. Narrowing the achievement gap, which funding inequities helped create, is the educational equivalent of the fight against cancer...while not life and death, addressing it is life altering for children's future.

When we know better, we must design our policies to do better — to do better for students and for our collective future.

It is far past time to embrace this moment to recommit ourselves to this effort that will require school leaders, parents, policymakers and the research community and activists to unite around these goals.