Earlier this month, LINK Houston and the Kinder Institute for Urban Research released a co-authored report examining where affordable housing and high-quality, affordable transportation co-exist in Houston. The city has a reputation as a place where the cost of living is low, but more and more that’s just a memory of a bygone Houston.

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

As Kinder Institute’s John Park and Luis Guajardo point out, nearly half of Houston households — approximately 425,000 — are considered Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed (ALICE). ALICE households have income that’s above the Federal Poverty Level but less than the basic cost of living, which is the cost of six basic household necessities: housing, child care, food, transportation, health care and a basic smartphone plan.

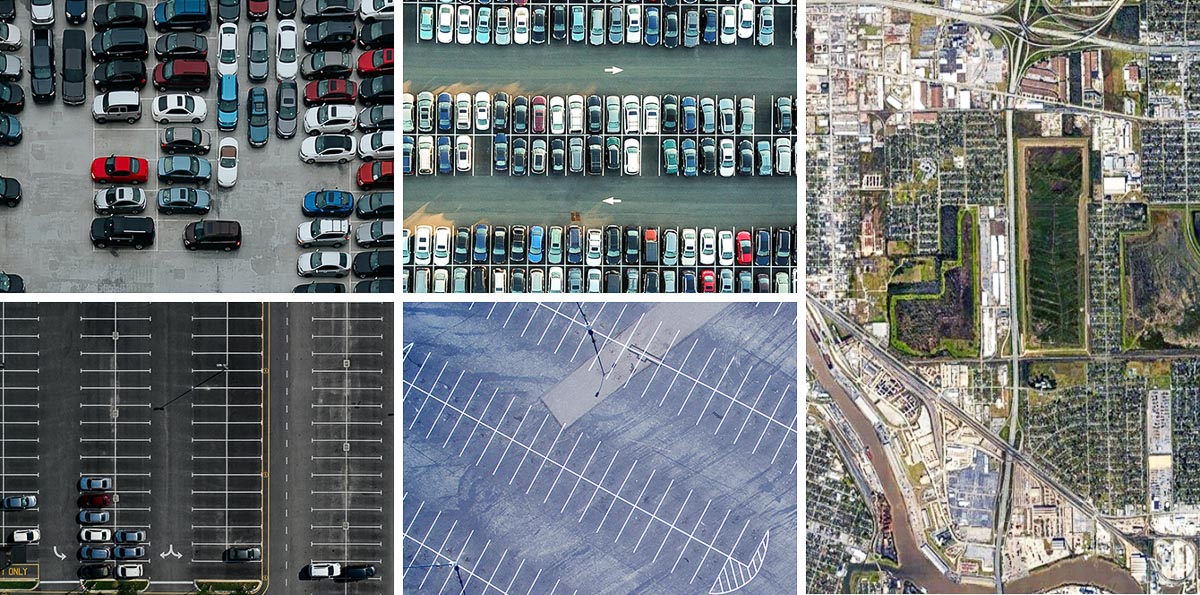

Households typically are considered “cost-burdened” when paying more than 30% of their income on housing alone. The problem of housing affordability in fast-growing, sprawling cities like Houston is worsened by the need for many residents to drive to get to work. Sprawling metro areas like the Houston region also offer fewer transportation options compared to denser metros like New York or San Francisco.

That means owning a car, which brings with it the added cost of car payments, insurance, gas and maintenance. Add that to the cost of housing and “the ‘cost-burden’ increases significantly for Houstonians, who, on average, spend roughly 45% of their income on housing and transportation combined. For those with low- to moderate-income levels, this cost also acts as a ‘barrier to entry’ to the city, which, in turn, limits their access to jobs, education and leisure,” according to Guajardo and Park.

All of this, of course, has only been further compounded in a city dealing with the dual economic blows of the coronavirus shutdown and the downturn in the energy industry.

As the 2020 Kinder Houston Area Survey, which was released earlier this week, shows, many Harris County households were struggling to meet the basic cost of living even before the pandemic. Those families are being hit hardest by the COVID-19 recession.

The scarcity of affordable housing is a problem in Houston, and the expense of owning a car, which is a necessity for many residents, exacerbates the issue.

Houston’s ‘newly poor’ neighborhoods

According to a report by the Economic Innovation Group, Houston has the second largest number of newly poor neighborhoods in the country behind Detroit. The Washington D.C. think tank defines “newly poor” as those that had a poverty rate below 20% in 1980 and a poverty rate of 30% or more in 2018. According to EIG’s analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data and American Community Survey 5-year estimates, the poverty rate across the city increased from 13% to 20% between 1980 and 2018.

Almost half-a-million Houstonians live below the poverty line.

The overwhelming majority of Harris County’s newly poor neighborhoods are located outside of Interstate 610, between the Loop and Beltway 8, which makes owning or using a car a necessity for most of the residents. As LINK Houston and Kinder Institute researchers have reported: Quality, affordable transportation options mostly are concentrated inside the Loop.

“Houston presents a dramatic example of high-poverty neighborhoods radiating out into the suburbs, sprawling alongside America’s now fourth-largest city,” write the authors of the EIG report.

Higher rates of auto loans in the suburbs

To help Houstonians in these neighborhoods, Joseph W. Kane, a senior research associate and associate fellow at the Brookings Institution, recommends an increase in transportation choices, including more affordable access to cars in areas where walking, biking and public transit aren’t viable options. He suggests safer rental and ride-hailing alternatives as a possible strategy. Kane also points to a need to protect borrowers from unfair lending practices and more support for those with high transportation costs, especially now, given the impact of the COVID-19 recession.

Kane has looked at how costly car loans could stall the nation’s economic recovery following the pandemic. He examined the distribution of Americans with car loan debt and found that the rates were often higher in the largest metro areas. Research cited by Kane shows that in the past decade, there has been a 54.7% increase in the amount of car loan debt in the U.S. — totaling close to $395 billion.

Between 2009 and 2019, subprime borrowers — those with credit scores below 620 — took on auto loans at a faster rate than other borrowers, according to Kane. Subprime borrowers face higher costs because of higher interest rates and longer loan terms. Many of these borrowers are low-income and have been targeted by predatory lending. In short, those who were taking on more auto loan debt were the most economically vulnerable before the pandemic, which has only increased their vulnerability.

A tool from the Urban Institute that maps debt in America — including overall, medical, student and auto — shows that 31% of Americans have auto loans. At the state level, 33% of Texans have auto loans. In Harris County, the auto loan rate is 30%, lower than the national average; however, those rates increase in the surrounding counties that form the Houston metro area, where the auto loan rate is 35% overall. At 39%, Brazoria County has the highest rate of residents with auto loans. The others are …

Chambers: 38%

Galveston: 36%

Montgomery: 36%

Waller: 36%

Fort Bend: 35%

Austin: 34%

Liberty: 34%

What can be done to address the issue?

Kane’s analysis led to a conclusion similar to that of the LINK Houston and Kinder Institute researchers. In their report, “Where Affordable Housing and Transportation Meet in Houston,” the researchers press the need for local leaders, policymakers and individuals to view the costs of housing and transportation as one when addressing affordability and considering where to live.

According to Kane: “While other escalating costs, including housing and student loans, are concerning and require more attention, infrastructure affordability is often overlooked by national and local policymakers. We need to better measure and address the escalating transportation costs that households have to cover while continuing to discuss the affordability of water, broadband and other infrastructure services.”

The pandemic has spotlighted the fact that many of those considered essential workers — grocery store employees, delivery drivers and personal care assistants, among others — earn low wages and are required to be onsite to do their jobs. In turn, many of these workers are dependent on older, unreliable vehicles to get to and from work. That, or they may be taking on the additional burden of car loan debt to buy a new or used vehicle.

Either way, these workers — whom we all depend on and who face a greater risk of COVID-19 infection — should have options for getting to jobs that don’t them at increased economic risk as well.