The couple, whose jobs allowed them both to work virtually, traded a one-bedroom apartment in Houston’s Midtown neighborhood for a 24-foot Class C RV—a 1995 Lazy Daze with less than 100,000 miles on the odometer. They bought it practically unseen off of Craigslist in Seattle, then took it on a coast-to-coast trip back to Houston.

After a remodel—the teal carpet had to go—and putting most of their belongings into storage, they hit the road again, this time in their new home, which they christened “Lady Bird.”

“It has everything we need. It’s basically a New York apartment on wheels,” said Jimenez, a software engineer.

They have been venturing up the west coast in recent weeks and pulled into Monterey, California, on Memorial Day.

“In a way, we’re doing this journey to look for a great place to settle down. ... But it’s the in-between places that surprise you. This is a beautiful seaside community, and I never would have thought about visiting it,” said McSwain, who works in museum programming, which, like so many things, had gone fully virtual.

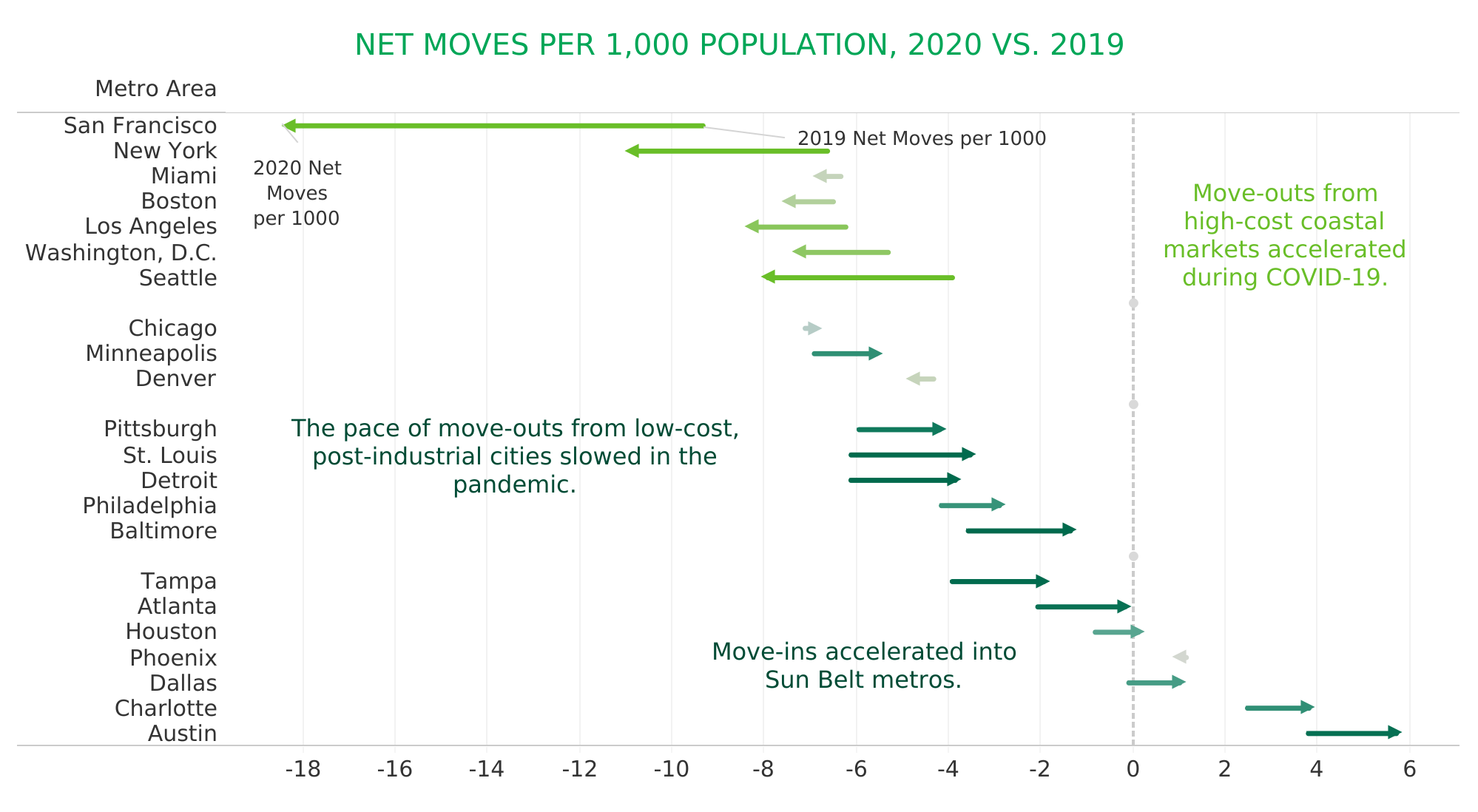

Source: CBRE

In a twist of irony, perhaps, these two new nomads are a short drive from San Francisco, one of the cities hardest hit by out-migration. From March to December 2020, the city had over 38,000 net move-outs—649% more than the year prior—according to the California Policy Lab, mirroring a trend for other high-cost cities.

The couple’s journey is an example of what the pandemic’s great uncoupling has done: Unmoored from a place-based job, people are reimagining their lives and their relationship to work. But most people didn’t embrace the #vanlife as fully as McSwain and Jimenez did.

Across the country, one class of people made more moves than any other: “Uptown individuals”—typically child-free, inner-city professionals, according to an analysis by commercial real estate firm CBRE. This group was 33% more likely to move last year than the year before.

Where did they go? They, along with a vast majority of all moves for all age groups, often lingereed within their original metro area but opted for a suburb, CBRE found. The same was true even for San Francisco, according to the California Policy Lab, where most moves last year were to new addresses in the Bay Area after fleeing the city proper.

Some people did flee their metros, and Sun Belt cities picked up a greater share of these than in previous years, according to CBRE’s analysis. Houston was relatively unaffected, with any out-migration offset by newcomers—suggesting, perhaps, that a recent population slide had at least come to a halt.

As predicted, a surge of migrants opted for smaller towns, suburbs and semi-rural destinations, according to CBRE. The full effects of this are still playing out, but there may be an upside for large cities like Houston, which are offer a relatively lower cost of living.

Data source: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland / Photo: Pexels

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland estimates that mid-size and small cities can expect a 10% increase in migration from large, expensive metropolitan areas. According to its estimates, if just 5% of remote workers flee these cities—think New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, D.C.—there could be as many as 862,000 new residents up for grabs.

If Houston is able to attract its share of remote workers, based on the Cleveland fed's model, for example, it could pick up over 75,000 new workers, or the equivalent of an entire year's worth of normal job growth. Dallas could get over 90,000, while Austin and San Antonio could expect around 25,000 apiece.

But perhaps the question to ask is not where people go, but why.

In a working paper, researchers Peter Haslag of Vanderbilt University and Daniel Weagley at the Georgia Institute of Technology probed 300,000 surveys of people who moved over the past four years to determine some of those factors. The data set, being from a national moving company, favored older people with larger families who made interstate moves. But that actually offers a look at potentially more-permanent moves, rather than opportunistic flights by digital nomads. This set is more likely to buy property, enroll kids in schools and have longer-term effects on a local economy.

“For the sake of thinking about the structures of cities … our data set is capturing the subset of individuals that could have a greater impact on things, potentially,” Haslag said.

The survey analysis showed that 2020 movers were more likely to cite lifestyle and family reasons rather than, say, a job relocation, as their main reason for moving. The pandemic itself was cited specifically as a factor in 10% of moves—significant but perhaps less than one would expect.

Higher-income movers were even more likely to move for non-job-related reasons—a better lifestyle, for example. Lower-income residents, meanwhile, were more likely to move because of financial reasons or to secure a new job.

Lifestyle is a broad category, but it could include being closer to nature, having more parks and trails, enduring less traffic or living under a different political climate. Some survey respondents also cited their state or community’s COVID-19 response as a reason, with those unhappy with strict lockdowns more likely to flee, they found.

For example, among the people who moved to Texas, more tended to be seeking a lower cost of living, but the state was more likely to lose residents whose primary reason for moving was lifestyle-driven.

That’s significant because, as we now know, the option for high-income workers to live anywhere is expected to become more common. If Texas, and perhaps more specifically, Texas cities, do not offer attractive living situations, they stand to lose out, which could unsettle real estate markets and tax bases.

Here’s the rub: Many of these attractive lifestyle factors are things that are in a community’s capacity to improve and to promote.

And lacking that, there’s always cash.

Some communities are angling to pick up remote workers in hopes of an economic windfall. Tulsa, Oklahoma, for example, is offering $10,000 toward a home purchase or $10,000 in cash throughout the year to lure new residents. But, Haslag said, the data suggests it will take more than a few incentives to attract and retain these workers.

“The time to compete is now,” Haslag said. “But what makes your city unique is even more important than, ‘I can give you an extra $5,000 if you move in’. If you give people the option to live anywhere in the world, the value of those other dimensions is likely going to speak more than a monetary one.”

But his research partner Weagley points out, any move to recruit remote workers will likely have an economic upside, as other studies have shown that knowledge workers tend to bring other economic benefits and create jobs.

Back in Monterey, where their RV offers a panoramic view of wherever they happen to be through three rear windows, McSwain and Jimenez can confirm that their life calculus has changed, in particular about where to live. Even with their extended family still based in Houston, their options abound.

“The year-plus of solitude has made it easier to think of a life outside of a city and the benefits of living outside a city,” said McSwain.

The jig may soon be up, however, as more employers try to reel back in their scattered workforce with hybrid schedules, carefully tip-toeing toward return-to-office mandates. In some surveys, almost half of workers say they will look for new jobs if remote flexibility is taken off the table.

McSwain’s own employer recently signaled that it was time to come back to the office and resume on-site programming at the museum.

Instead, she’s putting in her resignation, looking for a new remote opportunity, and enjoying every day on the open road.

“The payoff to come back to the job just doesn’t add up for me,” she said. “The quality of life for me now, it’s huge.”