Tamika L. Butler is a Midwesterner who grew up in Nebraska, moved to California to attend Stanford Law School and now calls Los Angeles home. She’s a Black woman, a wife, mother and self-described recovering lawyer who loves biking. (But she isn’t a cyclist.)

“I love being on my bike. And I love feeling free and having that mobility.”

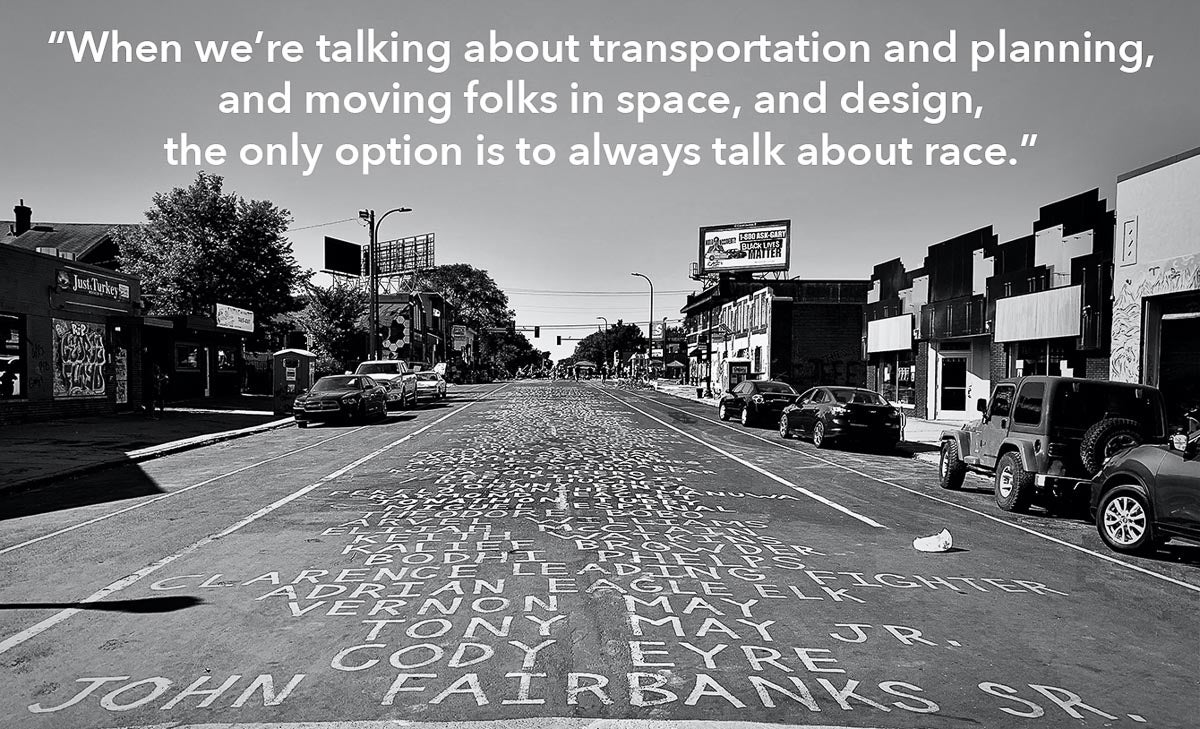

She’s passionate about transportation and transit — two issues she sees as inextricably knotted to race. As Executive Director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition (LACBC), this perspective was a challenge for some who didn’t see the need to overlap issues. To them, the sole business of the coalition was biking. Their experience afforded them the luxury of looking at biking and mobility as completely separate issues from race and racism. Butler, on the other hand, knows that for her and others the world is a much messier, more complex and potentially dangerous place. A place where these issues can’t be compartmentalized.

The link between mobility and race, social justice, criminal justice, housing and public health isn’t apparent to everyone; but it is to Butler. It has to be.

“I see transportation as this connection to other social issues.”

“Transportation has always been a part of the story of Black folks,” Butler, who is a national expert on issues related to the built environment, equity, anti-racism, diversity and inclusion, organizational behavior and change management, told an online audience during her recent Kinder Institute Forum lecture. “And when we’re talking about mobility, we’re not just talking about an ability to move, we’re talking about an ability to stay in place.”

Too often, Butler pointed out, communities are segregated from the core of resources and opportunities in large part because of transportation. And that access can be further limited if public transit service in America is slashed because of decreased ridership and revenues during the COVID-19 crisis.

“If you don’t have access to quality transportation, then you can’t have access to quality jobs. You can’t have access to quality health care. You can’t have access to quality education.”

Photo by Jéan Béller / Unsplash

Barring additional emergency relief funding from the federal government, transit officials in Boston, New York, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., are considering drastic service cuts to offset the pandemic’s decimation of ridership in those cities. These metros consistently have the highest transit ridership year after year and their transit budgets are made or broken by fare revenues. Nationwide, transit ridership is 76% below where it was before the pandemic, according to the American Public Transit Association.

Read our series examining the intersection of race, equity and public transit in America, featuring insights from transit advocates and experts.

Part 1: “Racism has shaped public transit, and it’s riddled with inequities”

Part 2: “What transit agencies get wrong about equity, and how to get it right”

Part 3: “What transit equity means to a transit-dependent rider in a car-centric city”

Part 4: “To tackle pandemic racism, we need to take action, not just take to social media”

Transit-advocacy nonprofits TransitCenter and the Center for Neighborhood Technology modeled the effect of a 50% service cut to peak service and a 30% cut to off-peak service in 10 regions of the U.S. and and found that these cuts would eliminate access to frequent transit for over 3 million people and 1.4 million jobs. The hardest hit would be Black and Hispanic riders, but the cuts would have a big impact on second- and third-shift workers and households without vehicles as well.

In the Houston area, where, before the pandemic, 80% of workers drove alone to their jobs each day, it’s easy to overlook the needs of the nearly 67,000 workers who commuted by public transportation. But COVID-19 has changed that. A large majority of these riders use transit to get to work, and if they aren’t working from home, it’s likely because they are essential workers. And most are people of color. During the pandemic, many Americans are finally recognizing the importance of grocery store employees, delivery drivers, health care and home care workers, bus drivers and others who were mostly invisible and taken for granted before the nation realized they were essential.

Butler pointed to Houston Metro as “an early leader” during the pandemic as safety precautions and protocols were put in place to protect essential workers who needed to get to hospitals and grocery stores, as well as their own front-line employees. “They realized the severity of the crisis and made some really prudent decisions on how to improve safety.”

Metro has made service modifications to local routes and park and ride routes, including frequency changes and route consolidation, in response to declines in ridership since mid-March. While local bus and light rail ridership has been cut in half, it has remained consistent over the past six months, according to the transit agency’s monthly ridership reports. From May to October, monthly local bus ridership averaged just over 2.9 million boardings, which is a 44% decrease from that period in 2019, In those six months, light rail ridership averaged roughly 746,000 boardings each month, which is down 52% compared to 2019. October ridership totals offer some consolation — they were the highest since the pandemic began.

The totals are evidence that the core group of residents who work in jobs that can’t be done from home and use public transit because they don’t drive or can’t afford a car remain reliant on Metro. Before the pandemic, the local bus network was responsible for two-thirds of Metro’s ridership. Since March, its share of total ridership has increased to more than 75%.

“We have to get out of a mindset where there are only certain people who are transit-dependent,” Butler said. “Because we are all dependent on the people who are transit-dependent. So, we’re all transit-dependent.”

Close to 60% of those who use public transportation in the Houston area have an annual household income of less than $40,000. And 77% are people of color, according to an extensive regional rider survey released in 2018. The survey, which was sponsored by the Houston-Galveston Area Council (H-GAC) and Metro, highlighted the importance of transit to the region’s economy — almost 90% of passengers surveyed were making trips for work (58%), shopping (20%) or to get to school (10%).

The survey also showed that 79% of transit users accessed the bus or light rail by walking, underscoring the growing concern over the availability of affordable housing that’s within walking distance of a Metro stop.

In May, the Kinder Institute and LINK Houston released “Where Affordable Housing and Transportation Meet in Houston,” a co-authored report based on an examination of where affordable housing and high-quality, affordable transportation coexist in the city. Half of Houston households are categorized as Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed, and the average Houston household spends roughly 45% of its income on housing and transportation combined. The report provides policy recommendations to help government and nongovernment stakeholders address affordability issues in the region by aligning housing and transportation development. The car-centric design of cities like Houston makes it necessary for residents to factor in the costs of both housing and transportation when looking for a place to live.

“Sometimes, transit agencies like to say, ‘Well, these are housing problems, these aren’t transportation problems,’” Butler said. “But as people are continuing to get pushed further and further out just so they can afford to live, they have to have access to jobs, especially as many of these people are transit-dependent.”

Those impacted most by cuts to transit service most likely won’t be at the table when these decisions are made, just as, historically, they haven’t been at the table when transportation and planning decisions — whether it be a new bike lane or a new freeway — have been made.

“If now is the time for transportation equity. If now is the time to make equity actionable, particularly in the transportation space and in the planning space, we can no longer just go into communities and say, ‘We have a bright idea.’ And when they say, ‘But what about my experience as an oppressed person? As a racialized person?’ We can’t just show up and say, ‘Well, I’m sorry, I’m just the housing person. I’m just the transportation person.’

“We have to start realizing that for many of us, we live at intersections of different identities. So, there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle, because we do not lead single-issue lives.”