Welcome to the weekly roundup of notable news, research and commentary on all things urbanism and urban policy from Houston, the Sun Belt and beyond. We were off last week, but we're back to our regularly scheduled programming. Dive in.

Title Page

Metro staff support a $6-billion widening of the 710 Freeway. Los Angeles Times.

Introduction

New Orleans Tries to Keep Mardi Gras Beads From Clogging Its Arteries. Seeker.

“...crews trying to keep that system flowing hauled more than 93,000 pounds (42,000 kilograms) of beads out of catch basins lining a five-block stretch of one downtown artery, a city official told reporters in January.”

“The Arc takes in beads after the parades end, cleans them up and repackages them for sale the following year. Sauer said collections have “skyrocketed” over the past two years, and it sold about 250,000 pounds of beads back to the public last year.”

Executive Summary

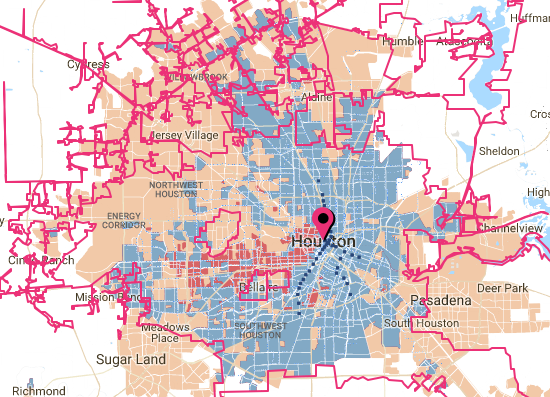

The Center for Neighborhood Technology recently released a new set of maps showing where potential transit gaps might be in various jurisdictions, including Houston, where an estimated 55.7 percent of households are underserved by transit.

In the AllTransit Gap Finder map below, blue indicates areas where transit service is already meeting a minimum threshold while white represents areas where the “market strength for transit service is low enough that adding transit would not represent an improvement.”

The map also looks at places considered underserved, including what AllTransit dubs the strongest transit markets in red (noticeably absent in Houston’s map), high transit markets in salmon, and medium transit markets in peach. For a full breakdown of how those are determined, click here.

But CityLab writer Jarrett Walker writes that these aren’t perfect measures because transit isn’t just about serving the highest-rider routes but providing a critical service to people who need it.

Walker breaks it down: “A transit gap is some kind of difference between transit service and transit need or demand. But need and demand are different things. A need means that there are people whose lives would be better if they had transit. A demand is an indication that transit service, if it were provided, would achieve high ridership.”

Thus, he concludes, “The notion of a transit gap confuses these two things. It will help people feel outraged about their transit service, but it won’t help local governments think clearly about what their priorities should be.”

Source: AllTransit.

Conclusion

Public space is understood as a good and unifying force in the urban discourse but some scholars are pushing back against the assumptions underpinning this idea and seeking to better understand what role exactly public space plays and conditions affect that role. Large public parks, for example, are touted as spaces where the diversity of a city’s people mix, thus encouraging some sort of shared collective identity and connection.

But scholars are “beginning to argue that simple numbers is not enough. Getting more and more people who are more and more different from each other in more and more spaces is not a sufficient condition for a democratic public sphere or for this urban ethic to develop.”

That’s according to Adam Kaasa, an urban culture scholar, who offered a bold proposal to reassess these shared spaces: a one-year moratorium on programming for public space. Part of a two-day discussion at London’s Garden Museum responding to the mayor’s announcement that he would come up with rules managing the use of semi-public spaces in the city. Though the comments are targeted, then, at London’s public spaces, the insights travel well.

“Programming has edged out design,” argues Kaasa, and brings it with a tangle of complications, including that it controls how people will use the public space more narrowly than design seeks to and that its major metric of success is crowd size. Doing away with programming for one year, he posits, would “open up space and imagination” to envision other possibilities for the space, perhaps ones that facilitate connection and the urban ethic more deeply.

Endnotes

The first of its kind in 1965, the Astrodome was always a multipurpose building. Along the way it became more than just about history or sports. It was about Houston. These are just a few personal samples of what this building can bring to the table again. Have a great evening. pic.twitter.com/dHKM2JeZzG

— Mike Acosta (@AstrosTalk) February 13, 2018