The past few months have been terrifying, but also cathartic. The pandemic has shaken most of us from a false sense of security about our individual health, the efficacy of our cities to provide a high quality of life, and forced us to question many of our daily habits — how we live, work, travel and exercise, as well as how we source the food we eat. Our connection to nature. The primary lesson we, once again, must learn is that cities are not divorced from nature. They are a part of the larger biome in which they’re located.

As planners and designers, we are trained to think holistically. While these fields of study promote cities as beneficial, no city is perfect — not even close, and the vulnerabilities and interconnections of the global supply chain has impacted all of us in unforeseen ways. In this post and others, I will delve into the benefits of reconnecting to basic processes that support our daily needs, such as the growing of plants for food, increasing equity in our local communities and local food security. I will look at models from the past that promoted urban gardens and gardeners, and show what worked and what did not. I will discuss the opportunities and challenges of being an urban gardener, what is needed to set up a garden of your own, and what laws and standards stand in the way of making cities better at promoting urban gardens.

All good in the ‘agri hood’

If you work in the service economy, commuting to work has largely become a thing of the past. The amount of time wasted getting to and from traditional workplaces has been well documented. One notable study concluded that before the pandemic, Americans wasted an average of 54 hours a year commuting. The accumulated negative effects of pollution and stress that result from commuting alone by car — as most Americans do — are significant.

Smart city technology is something that can help us all make better choices about when — and how — we travel. The ability to come to the office for collaboration and culture, and stay home for focused work is an idea that saves time, is better for the environment and is a smarter use of limited resources. It appears the hybrid workplace is an idea whose time has come. What hasn’t yet taken hold is the connection between these changes in behaviors and how cities could respond.

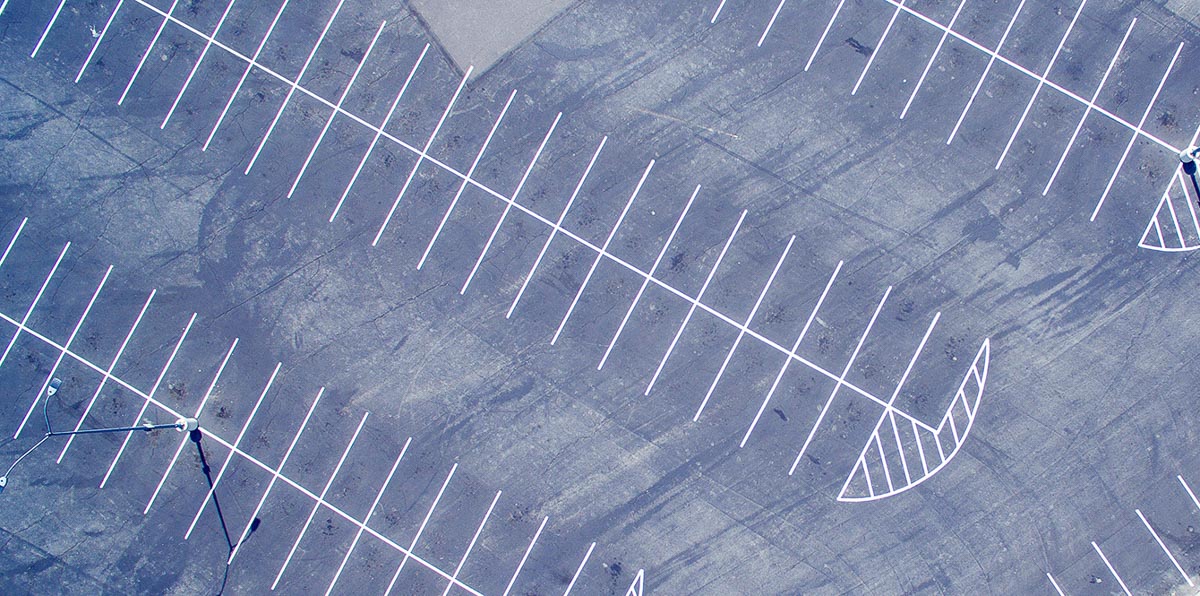

Commuting is just one example of where there are opportunities for planners to use changes in behavior as a point of departure to propose new ways for how cities function. What are the health impacts of our cities suddenly overdesigned for cars? How can our city infrastructure (roads, utilities) perform better, not only as conduits to move people and goods, but as contributors to natural systems? Urban phenomena such as smog, poor water quality and the ‘heat island effect’ can be mitigated by greening our streets, electrifying our vehicles and planting our parking lots.

Our ability to grow plants as a means of providing fresher, cooler air will be important in city design, both in terms of wellness and to attract the best and brightest talent. In a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, Richard Florida discussed the phenomenon of ‘zoom cities,’ which attract remote workers by creating an image of a higher quality of life.

He wrote: “For cities, remote work changes the focus from luring companies with special deals to luring talent with services and amenities. Communities can invest precious tax dollars more wisely and cost-effectively on things like better schools and public services, parks and green spaces, safer streets, bike lanes and walkable neighborhoods.”

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez / Unsplash

Stay at home

Spending so much time at home over the past year has shined a light on how unequipped many of our neighborhoods are for supporting daily needs such as food production. Current thinking in city planning, popularized by cities as diverse as Portland, Oregon, Paris and Melbourne, have focused their energies on promoting the ‘20-minute neighborhood.’

What this thinking implies is a city designed to support local behaviors. To improve convenience and local connection to essential services and needs within a 20-minute walk, bike or scooter ride from home will require structural shifts in city design that will take some time to overcome. Challenges include the centralization of the workplace within central business districts, the advent of big-box retail as a competitive tool to increase tax bases and in buying habits shaped by online platforms (which some argue hurt local businesses).

Whether buying a house and raising a family, or starting a business, people make a big commitment — and take a big risk — when choosing a neighborhood. To manage the public realm in a fashion that promotes and supports those who are willing to invest in a neighborhood, planners need to think like entrepreneurs.

Promoting urban gardens can help.

Picking local over global

Few would argue that our traditional street standards aren’t over designed, resulting in significant cost to operate and maintain. An area of focus of late has been on how cities are rethinking overly wide streets and left-over spaces within the city grid.

One idea gaining popularity is easement gardens that can be easily integrated into the existing city fabric. A recent study found there are roughly 100 square miles of surface parking (four times the size of Manhattan) in Los Angeles County alone, space that’s being underutilized due to changes in behaviors around the car. Leaders in the urban garden movement, such as Ron Finley in South Central L.A., have successfully lobbied city leaders for changes in the street codes that allow urban gardens to be cultivated and maintained by adjacent landowners.

Photo by Robert Ruggiero / Unsplash

Planting a seed

There are many benefits to urban gardening, including increasing biodiversity and improving soil condition. Producing food locally dramatically decreases our carbon footprint — to almost nothing — in the growing, packaging and shipping of food. The health benefits of gardening are significant as well.

Do we have enough cultural buy-in to make the changes in zoning, land use and parking standards necessary to promote a community of urban gardeners? Do our laws allow for this flexible use of land? And what about the use of water resources?

Cities like Detroit offer a model of what is possible. More than 1,400 urban gardens currently exist there. Planners are focusing on key planning priorities such as alleviating food insecurity and promoting equity in land use. In an Urban Land Institute study, communities across the country noted “agri hoods” as being the most desirable amenity to have a home near, far preferred to more traditional amenities such as golf courses or community parks.

Reaping the health benefits

Of the many noticeable changes to the urban environment in the past year, the increasing popularity of gardening is one of the most profound. It is human to want to connect to the changing of seasons, planting, cultivating and harvesting. All around my neighborhood, I see people changing their habits around food, relying less on grocery stores for fresh veggies and herbs, and instead turning to their own garden plots to provide (at least) a portion of their weekly food needs.

Research shows the benefits of home gardening include relieving stress, increasing physical activity and improving emotional well-being. A recent study from Princeton University found that out of 15 daily leisure activities, gardening is one of the most beneficial activities for mental and emotional health.

“Gardening combines so many things that are positive for mental health — being outdoors around plants and nature, physical exercise,” said Diana Martin, director of communications and marketing at the Rodale Institute, a nonprofit focused on promoting the benefits of organic farming. “Something about growing food, connecting with the earth and sharing the bounty with your neighbors and community can help you feel rooted, connected and grateful.”

In an Urban Land Institute study, communities across the country noted “agri hoods” as being the most desirable amenity to have nearby.

Photo source: Wikimedia Commons

Measuring wellness

The field of urban design has focused intensively for a long while on the role access to nature plays on human psychology and health. There has been intensive study on the design of prisons, hospitals and senior housing that shows the benefits of visual connection to plants and natural landscape, which has been proven to improve socialization, accelerate healing and improve cognitive ability. In one study, two groups of patients where isolated following the same surgery, the group with visual access to nature recovered up to a day faster than those without. They also used fewer strong painkillers, gave fewer negative evaluations of the hospital staff and had fewer postoperative complications.

Some cities have already incorporated urban gardens, citing similar scientific studies that support the value of proximity to nature in wellness objectives. Singapore’s wellness gardens are an example. I predict in the future, cities will be measured by objectives and key results that document personal well-being in the quest for attracting top talent. Integrating more nature into the built environment will be essential to these ends.

We see a confluence of factors moving average citizens toward a closer connection with natural systems. First, the pandemic has forced us all to stay at home and take stock of our surroundings, which has led to seeing opportunities for gaining new skills (such as gardening) to better control our environment. Second, a shift away from globalism has forced us to question the sourcing of the food we eat, its impact on the environment and our health. Third, we recognize that the infrastructure of our cities has been designed and maintained for a different era, and is ripe to be reconceived in a manner that promotes biodiversity, social equity and community connection. Fourth, we recognize that growing things benefits our physical and emotional well-being and the local environment. Fifth, we recognize that urban gardens are a value proposition in the war for talent that will differentiate progressive cities from their competitors.

Nate Cherry is a planning director for Gensler's Los Angeles-based Planning and Urban Design group. Gensler is a global architecture, design and planning firm.

The views, information or opinions expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research.