When I was asked to participate in this series examining the intersection of race, equity and public transit in America, I scribbled down pages of things I wanted to say. None of it new. Many were things I’ve said before on this panel or that webinar. Many were things I’ve heard from other people of color — often women of color — that moved me and resonated deeply.

I started composing my piece. I wanted to keep it short. To the point. I knew I was writing for an academic institution (potentially a predominately academic audience), but I wanted this piece to be accessible and to the point. I did not want to overly rely on statistics and buy into the false white supremacist belief that the only opinions worth listening to were those based on quantitative data produced by educational institutions or research organizations with a history of keeping certain people out. Sure, I was prepared for the typical retort from those who say, that without the data, what I write is just an opinion, but I did not want to center those views.

Read our series examining the intersection of race, equity and public transit in America, featuring insights from transit advocates and experts.

Part 1: “Racism has shaped public transit, and it’s riddled with inequities”

Part 2: “What transit agencies get wrong about equity, and how to get it right”

Part 3: “What transit equity means to a transit-dependent rider in a car-centric city”

Part 4: “To tackle pandemic racism, we need to take action, not just take to social media”

Instead, I wanted to center the views of those most impacted by our transit systems and decisions that affect their ability to move freely throughout their communities. I wanted to center the views of those who do not just peek in when it is fashionable to examine the intersection of race, equity and public transit, but those who live it every single day. Those who cannot do the research, write a piece, feel better that they have contributed to the discourse on racism in transportation and then go back to their lives and the way they typically do things.

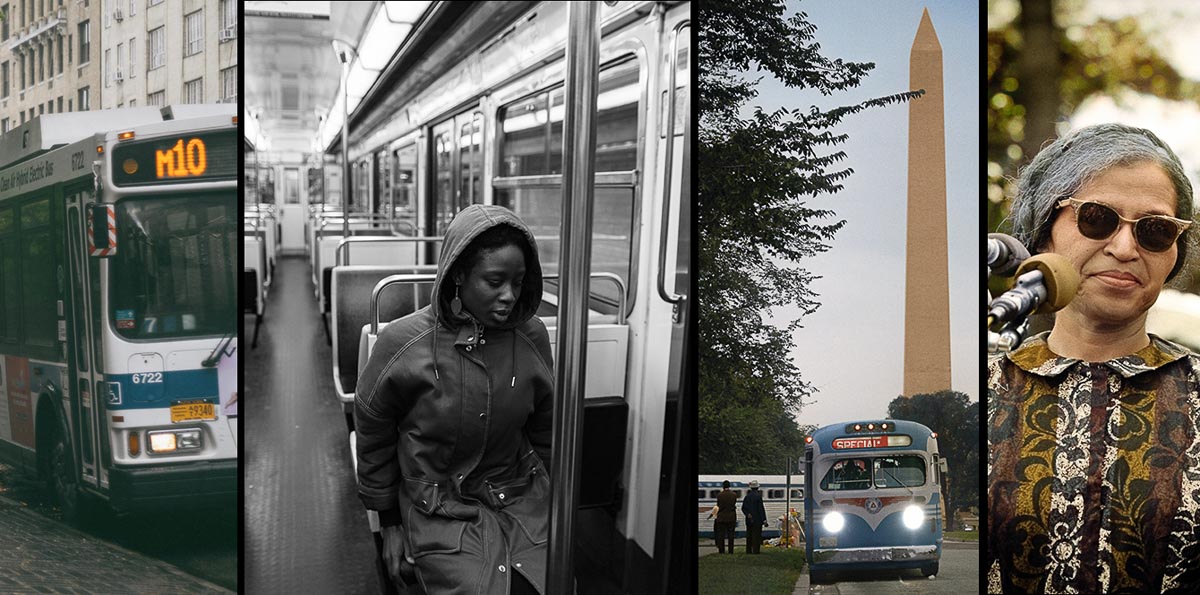

I wanted to center the Black women who have been fighting at these intersections since the very beginning and are still fighting today: Ms. Rosa, Ms. Janis, Ms. Ayanna, and all of the other grandmothers, aunties and moms out there speaking up, sitting down and carrying whole movements on their backs. I wanted to uphold the belief that life experience is just as valid as academic or professional experience. I wanted to do a lot. Carrying all of these goals was heavy.

Many Black women encounter this heaviness daily. We must carry the burden of knowing that as Black women we must stay strong, support our families and communities, fight for justice, and take the risk to speak out when others will not.

So, I sat down and I wrote. Holding all of that heaviness. Typing away with one thought after the next about this intersection where far too many have only recently arrived on their journey to urban policy awakening. But then that other thing that’s always looming hit me hard: I am Black in America. Not that I ever forgot. I can’t forget. It could cost me my life.

But sometimes I get so lost trying to get an assignment just right that I momentarily allow myself to be one of those transit advocates/planners/place-makers/urbanists (insert your favorite descriptor here) who drive me nuts. The ones who are buried so deep in talking about bus routes/speed humps/cars/density/bike lanes/slow streets (insert your favorite transportation passion issue here) that they lose sight of the actual context of the experience of many who ride transit. Maybe it’s not that they have lost that context. Maybe they never took the time to listen deeply and let it hit them so hard that it stays with them.

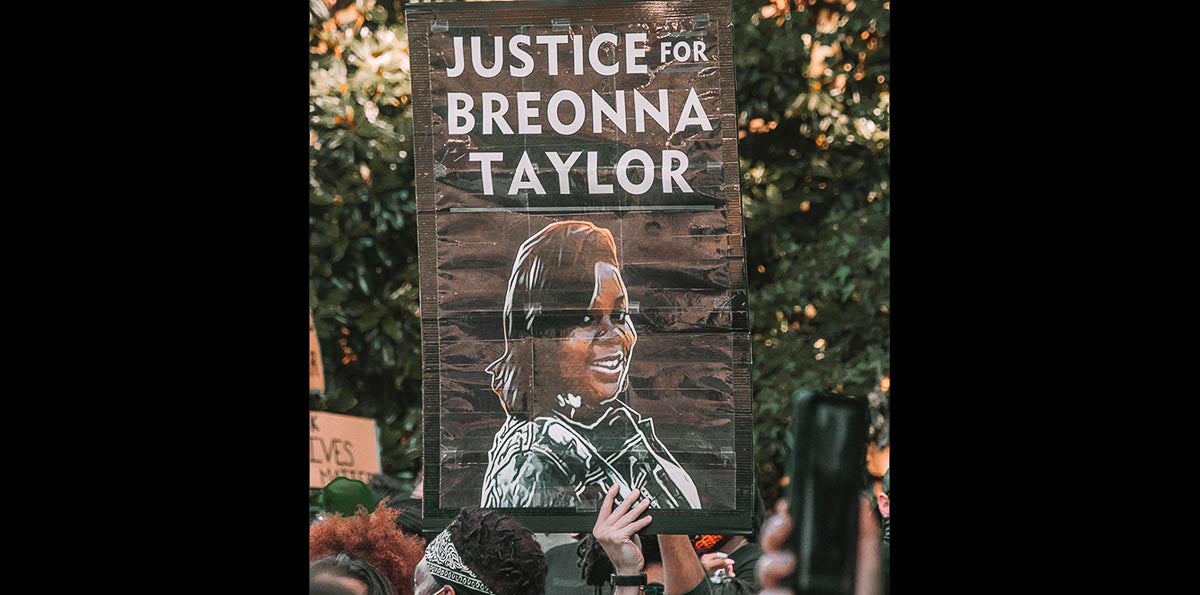

I felt that heavy and consistent weight the morning I woke up and went online to search for the first piece in this series. What I found instead was the name of another Black American trending. I woke up wondering if Jacob Blake would live. I woke up wondering why no one was talking about Anthony McClain. I woke up wondering if more people would buy a magazine with a portrait of Breonna Taylor on the cover than would take action to demand her killers be charged. Wondering how many would decide to do more than just tweet about justice and instead be willing to fight, vote and relinquish power to achieve it.

I woke up in a world where all the Black people in my life were in mourning, were scared, were triggered and were exhausted. I woke up in a world where most of the non-Black people on my Zoom calls were more informed and concerned about the weather in California than the shooting of another Black person in America, and the toll and weight that a shooting takes on Black folks as it lights up our timelines, fills our thoughts and dreams, and is on our minds during work calls and yes, even our transit trips.

People kept saying things would be different after George Floyd. Organizations, policymakers, celebrities … everyone said things would be different going forward. Well, how many of those people or organizations did or said something on that Monday morning? Were things different or were people just relieved that we finally weren’t talking about race so much anymore and just kept going on with business as usual? How many went back to saying nothing and operating like nothing big or traumatic happened after a Black life was lost? Just like before George Floyd.

I woke knowing that maybe things haven’t changed as much as some of us hoped. But I knew something had changed for me. I woke up knowing the prompt that I was assigned to write about was hard to wrap my head around without getting distracted. Honestly, it was not a distraction that was pulling my mind away — it was my reality. The constant thought of how to be Black and live.

As a Black person, the idea that I would have the privilege to ever just be does not seem like it will ever be a reality. The idea that I could just sit and work. The idea that I could develop a hobby. The idea that I could just play with my kid. The idea that I could just lead an organization. The idea that I could just drive in a car with my family. The idea that I could just ride public transit. The idea that I could just write about the intersection of transit, equity and race without holding the heaviness of the fact that, as a Black person, I can’t do any of these things without being very aware that I’m doing them while Black. I have to do and be and exist while constantly being aware of racism, anti-Blackness and white supremacy — and working like hell to dismantle and overcome them.

With that thought consuming my attention, I decided to focus on the fact that if we truly want to look at the intersection of race, equity and transportation, we have to focus on the fact that white supremacy, the policing of Black bodies and how we move in space have always been something that many non-Black folks have chosen to look away from. You should no longer look away. We must face the broken systems in our country and dismantle them completely, then build something new in their place. That includes transportation and transit systems.

When we start building new transportation systems and structures not rooted in white supremacy, anti-Blackness and land theft, we have to ask ourselves who has the power in building that system. The first article in this series came from Christof Spieler, who wrote: “We in the transit world, all of us who are involved in decisions about what kind of transit service to provide, and where and how to provide it, are the stewards of systems that have racism deeply rooted in them. And, unless we step back and question ourselves, are willing to have uncomfortable conversations, and share our power, we will continue to perpetuate that racism.”

Let’s look at who “we in the transit world” currently means.

According to the 2019 TransitCenter, “Who Rules Transit?” transit tool, the world of who is riding transit is drastically different than the world of who is leading, planning and making transit decisions. Many of the articles in this series are focused on transit as a service and agencies as providers. That’s true, but it’s also true that transit agencies are vital employers in the communities that they serve.

As with many industries and companies in our country — even those with the most heartfelt Black Lives Matter statements — the demographics of transit agency employees do not match those of their communities or their riders. The transit tool states that “census numbers reveal that the majority of transit riders are women, people of color and people with low income.” Those in positions of power at service providers? Not so much.

The situation does not get much better when you look at the leadership of these agencies’ demographics across various categories. TransitCenter reports that women comprise less than half of the transit agency workforce, that fewer than five transit agency CEOs are women, and that transit agency boards predominately are white, with just two people of color filling the CEO role among the largest agencies in the country.

Compare this to who the American Public Transportation Association says is riding transit in their 2017 Who Rides Public Transportation report. People of color make up a majority of riders at 60%, with Black people composing 24% of ridership — this means Black people are overrepresented among riders (compared to the general population) and underrepresented in agency leadership (compared to the ridership numbers and the general population). When you look at demographics by mode of transit, Black and brown folks are more likely to ride buses, while white people are more likely to ride rail.

The stats in those last three paragraphs are a problem.

Someone might read this and think I’m saying that it’s time to just hire more people of color. More women. More people with disabilities. More Indigenous people. More Black people. More queer people. More people who have experienced oppression in all facets of their lives and know that oppression does not stop when they get onto transit.

Yes, I am all for hiring those folks. More people need to be hired who understand that getting to transit, waiting for transit, boarding transit and paying for transit is probably just one of the first forms of oppression they will have to face that day.

But that is not enough. These folks have to be put into decision-making positions. Their experience must be appreciated. They cannot be relegated to diversity hires or outreach coordinators. Protecting suburbs, Jim Crow, redlining, housing appraisals and many other policies and practices have left their imprint across the United States and Canada. There are communities and groups of people whose neighborhoods have been planned without their input, and in some cases with the explicit or implicit goal of making the neighborhood great again, without them.

In addition to being cut out of the decision-making process, planning has been implemented to keep people in historically oppressed groups on the other side of the tracks. This has resulted in some people being left without access to reliable transit, using their communities as dumping grounds for undesirable and toxic land uses, and literally tearing their communities apart with highways. This reality is proof that the foundation of racism many transportation and transit systems were built on, stays firmly in place today.

Spieler is right when he says that it’s time for the transit world’s decision-makers to get real about racism. Transportation, transit and planning are not race-neutral. It is not just time to step back to question and have uncomfortable conversations about this; it is time to step forward, get angry and get honest about why people in power are reluctant to relinquish their power. And it is time to do something about that. If stepping back feels safer or more comfortable, then do it. Just get out of the way so that those who are ready to lead and build transit differently can do so.

Those of us in the transit world have to acknowledge and own the fact that our work can either start to dismantle that foundation of white supremacy or it can fortify it as our decisions perpetuate racism, anti-Blackness and inequity.

First, we have to start with race. We cannot say that Black Lives Matter and that our work is not racist if we are not willing to even broach a conversation about what racism is and how it appears in our projects, organizations and service. If the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and the genocide against Black people have shown us anything, it is that structural racism impacts everything — from who gets sick, to who gets to walk or run in their neighborhood, to who is an essential employee and how they get to work.

We may want to ignore the role that racism plays in our society. We may want to pretend that racism doesn’t exist. But that won’t make it so. Any real examination of an intersection that includes equity must start with race and what it takes to be anti-racist.

If that makes people uncomfortable and want to retreat to conversations about diversity and inclusion, then ask yourself why. Then, be clear that efforts to diversify the world of transit decision-makers are important, but they aren’t the solution. Having people with “exotic” faces, hair and names will not make transit more just if those people are not part of inclusive organizations. Inclusivity is not just everyone feeling like they belong. This is 2020. If that is your definition of inclusion, you are behind. To catch up, realize that true inclusion requires a shift in power. Diverse people are beyond just needing a seat at the table, we need to be at the head of that boardroom table.

Beyond that, we need to have full participation, decision-making power and culture-setting ability to tell people who are used to having a seat at the table to pick up their chair and meet the community wherever they are — including the corner, the temple, the stoop, and even on the bus. Inclusion means that people can show up as their full selves, with dignity, and with the ability to guide, lead and wield power with anti-racism firmly centered.

If you examine the intersection of race, equity and public transit, and look at the demographics of the transit world’s decision-makers, it is clear who currently has that power. The transit world should want to change what groups of people feel safe on transit. The transit world should want to change who has longer wait times on transit. The transit world should want to change who has access to transit. The transit world should want to change who gets a place to sit and seek shade while waiting for transit. The transit world should want to change public investment in transit.

All of these things should have a positive impact on the inequities in transit. But they will not change who is planning transit. They will not change who is in the decision-making positions in transit. Those things will require taking a hard look at why it is more normalized to see Black lives lost at the hands of police than it is to see Black people lead the way in transit.

Sit with that. It’s heavy. Then, work like hell to change it.

Also, Stop Killing Black People.

Tamika L. Butler is a national expert and speaker on issues related to built environment, equity, anti-racism, diversity and inclusion, organizational behavior, and change management.