Sunnyside is one of Houston’s oldest historically black communities. It was founded in 1912 and developed exclusively for African-American residents during a time when race-based deed restrictions were common and enforced in a city known for its lack of zoning. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down such restrictions in 1948, making them unenforceable and illegal.

The south-central neighborhood and those who live there have ridden highs and lows over the years. It was called the “Baby River Oaks” in the 1970s and 80s when businesses flourished in the area, but has been lodged in a lengthy economic decline since. In 2018, the Houston Chronicle reported on data analysis showing the neighborhood lost 200 businesses between 2006 and 2016. Within those 10 years, the neighborhood’s unemployment rate ballooned to 29% — the highest in Houston, according to the Chronicle.

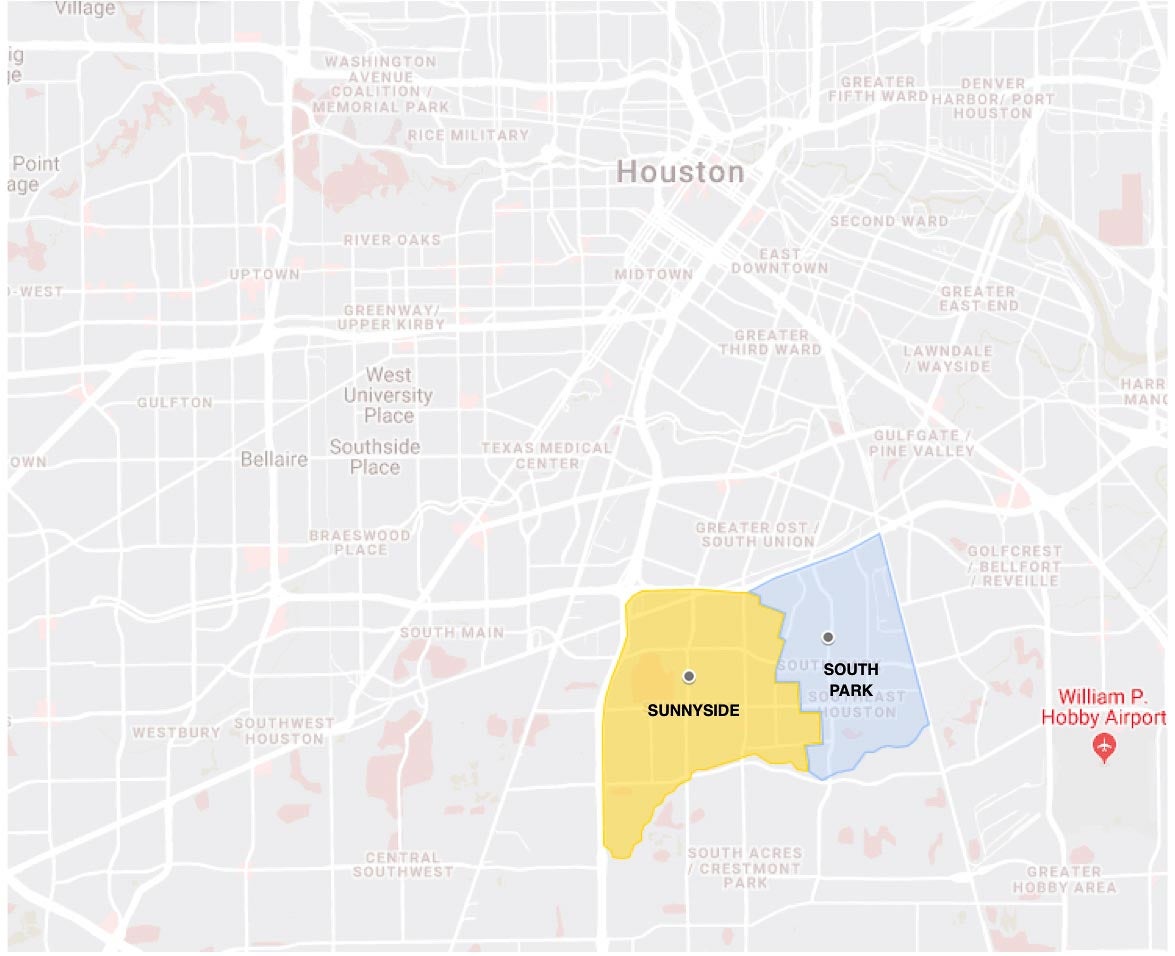

Immediately east of Sunnyside is South Park, which was developed following World War II. The war’s significance to returning veterans wasn’t lost on planners who named its streets for military leaders and battles, including Pershing, Forrestal, Eisenhower, Bataan, Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. In the 1950s and 60s, most of South Park’s residents were white, but the demographics shifted in the 70s and 80s. In the past, some drew a correlation between the desegregation of schools in the area and the change in the population as whites moved to suburbs farther from the city’s center.

Although Sunnyside and South Park face challenges in the areas of crime and safety, economic development, improving public transportation and access to healthy food options, there are a number of reasons for residents to feel optimistic about the area’s future, according to the results of the Sunnyside Strong survey.

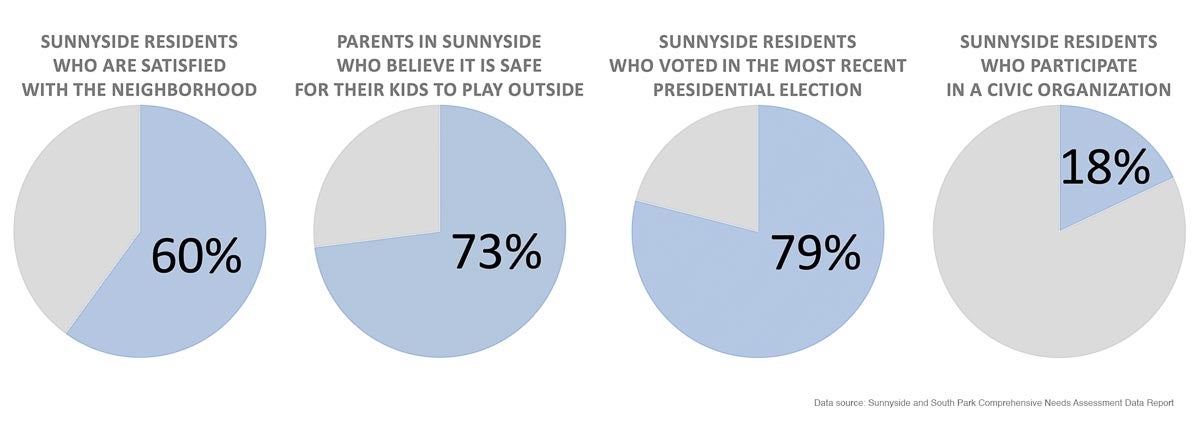

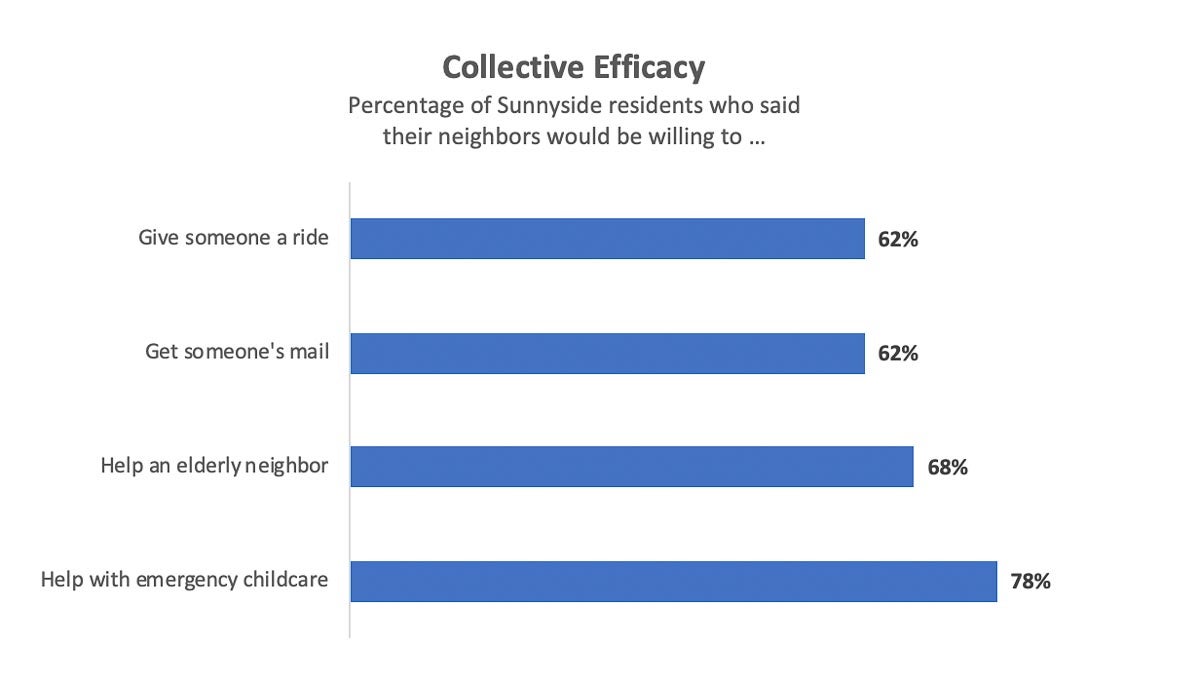

Neighborhood satisfaction among respondents was high (60%) and nearly three-quarters of parents said it is safe for their child to play outside. The extent to which respondents believed their neighbors were helpful and looked out for each other — known as collective efficacy — was also high, according to the survey, which was a collaborative effort by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, the Houston Area Urban League, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Interdisciplinary Research Leaders program and Sunnyside and South Park community leaders.

In addition to the rate of collective efficacy, survey results showed a high level of civic participation and high expectations among parents that their children will attend college, all of which indicate the community’s fundamental social structure is strong.

“As a sociologist, I believe nothing is more important than the social fabric of a neighborhood,” says Rachel Kimbro, a Rice University sociology professor and one of the researchers who conducted the survey. “When residents trust and look out for each other, even factors like high poverty levels are not as impactful on wellbeing.”

Kimbro, the founding director of the Kinder Institute’s Urban Health Program, also points to Sunnyside’s extremely high rate of voter participation as an indicator of robust civic engagement and community investment.

“These aspects of Sunnyside mean the foundation for neighborhood improvements is very strong,” she says. “Investments in the neighborhood, whether in infrastructure or retail or housing, have a better chance of succeeding because the social fabric is so strong.”

Urban cowboys, revitalization and the creep of gentrification

A unique mix of rural and urban (“rurban”) characteristics are found in Sunnyside and South Park. There are streets of tidy 2- to 3-bedroom single-family homes and townhomes, but also large open lots and power-line easements where horses graze.

The two neighborhoods combined are bordered by Loop 610 South to the north, Highway 288 to the west, Sims Bayou to the south and Mykawa Road to the east. They're in a desirable location with close proximity to the Texas Medical Center, the Museum District and Downtown, so it’s not surprising that gentrifying has begun. A 2018 Kinder Institute report on neighborhood gentrification in Harris County showed Sunnyside has a high probability for it. That can be a blade that cuts both ways for residents who want to revitalize the neighborhood without stripping it of its heritage.

Residents of Sunnyside and South Park have many reasons to feel optimistic about the area’s future, according to the results of the Sunnyside Strong survey.

Community buy-in is key to getting a true picture

The research team was fully committed to ensuring the community was engaged in the project.

“Most survey research is not community-engaged,” Kimbro says. “So, traditional surveys may be missing the factors that are most important to a community.”

To help hold researchers accountable, the team set up a community advisory board that was involved in every step of the process, from informing the design and administration of the survey, to having input on how the findings were disseminated.

The effort paid off.

“We were able to include survey questions which were most relevant to the community, rather than coming in with our preconceived notions about what would be important,” Kimbro says. “This meant, for example, we added additional questions pertinent to access to public transportation, as well as a number of questions about K-12 education that the community was interested in.”

The interest in education didn’t stop at primary and secondary schools for the parents participating in the survey.

While less than 10% of the residents in the sample had a college degree, the respondents were overwhelmingly optimistic their children would one day attend college. Among the sample residents who had at least one child under the age of 18 living in their household, 98% expected them to pursue a college education, and 97% said their children hoped to go to college.

Concerns include flooding and drainage

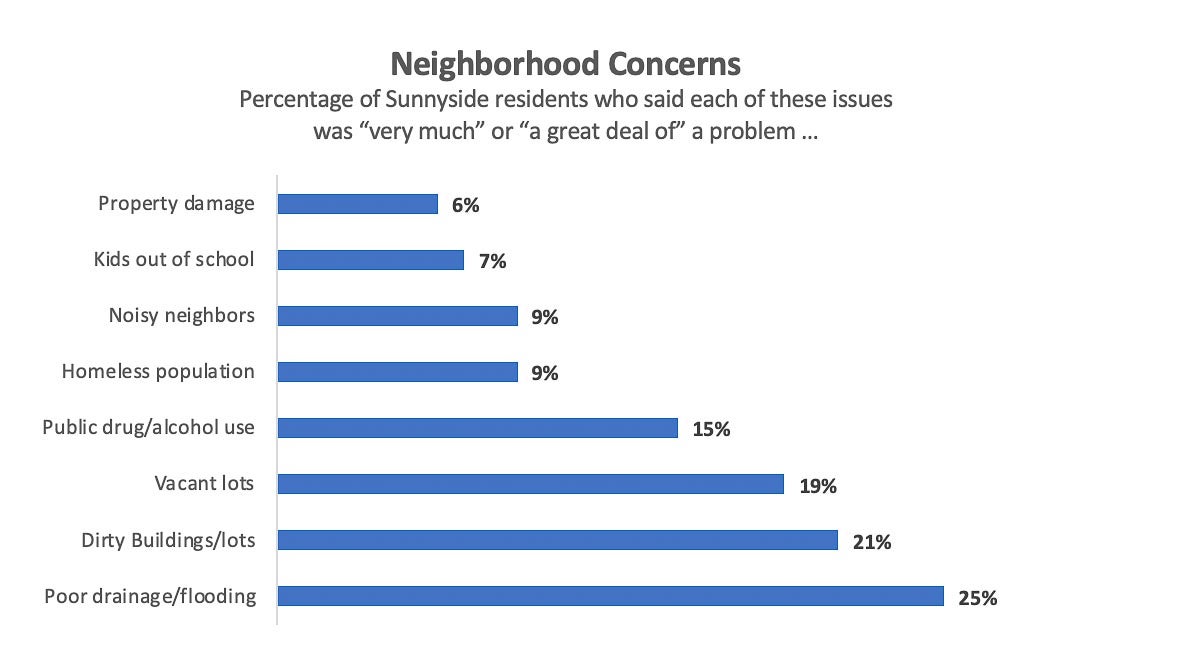

Residents were asked for their views on the neighborhood’s biggest problems, as well as issues such as safety and security, transportation, housing, education and health and health care.

The threat of flooding and poor drainage, dilapidated buildings and neglected properties, and vacant lots were the three biggest concerns, respectively. Worries about flooding aren't surprising given that the homes of close to a third of respondents were damaged by natural disasters such as hurricanes in the past decade, namely Hurricanes Harvey (64%) and Ike (30.6%). Almost 40% of residents with damaged homes said repairs have yet to be made.

How crime impacts the community

Neighborhood shootings, theft, drug use, traffic and drug dealing were what respondents worried about the most among issues of safety and security.

Fear of crime prevents many Sunnyside residents from moving about freely in the area on foot, with more than 75% of participants saying it limited where they would walk alone. For 31% of those, that fear was a factor both day and night, while 45% said it was a consideration only after dark.

When asked about transportation, only 36% said concerns about crime had ever prevented them from walking or biking in the neighborhood. Traffic safety, fear of stray animals and low-quality walking and bike paths were the factors cited most by respondents, 75% of whom said a car was their main mode of transportation.

Improvements needed in the health of residents

Chronic health problems are a concern for the neighborhood. More than one-third of respondents reported they or someone in their household had been diagnosed with high blood pressure, and one-fifth reported arthritis and diabetes. The majority of respondents rated their health as “average” or “good,” and only 13% said their health was “very good.”

In all, 86% of residents said at least one adult in their household had health insurance.

Data is being used to lobby for change

“Our community advisory board is taking our data and advocating for change in their neighborhood,” Kimbro says. “In fact, they used our data to successfully obtain a grant to help them do this.”

In June, Houston Mayor Sylvester Turners announced Sunnyside as one of five new additions to his Complete Communities initiative, a public-private effort to guide investment that improves amenities and services in select neighborhoods.

“We’re hopeful that will help resources come to Sunnyside.”

Kimbro reiterates the strength of existing relationships among the residents, and the power they bring to their organizing efforts.

“When we held a community meeting to present our survey findings, more than 100 Sunnyside residents attended,” she says. “The Sunnyside community is invested in its own future in a major way.”