Charlotte’s newly christened streetcar had a rough first week.

One streetcar crashed into an SUV after its driver lost control of its vehicle, city officials said.

A reporter laced up her sneakers and raced the streetcar, beating it to the end of the 1.4-mile line by a full two minutes.

And the local newspaper observed much lower ridership on the streetcar’s opening day compared to the city’s light rail opening a few years ago.

Charlotte’s new Gold Line streetcar is the latest in a modern streetcar revival in American cities. And it’s the latest to reignite the debate about how effect streetcars really are.

In Cincinnati, Tampa Bay, Seattle and Little Rock, among other places, city leaders are following the lead of Portland, the gold standard in modern streetcar projects, as they try to provide a high-end transit option with a nostalgic feel to urban residents and visitors.

But the opening of the fast-growing city’s new transit line – envisioned as eventually the primary east-to-west transit option through downtown Charlotte – comes as transportation and planning experts are debating whether streetcar lines are even a wise investments in the first place.

As evidence from the recent projects pour in, transportation-focused academics are quickly reaching a consensus that they aren’t. Or at very least, they aren’t in the way they’re usually built, without dedicated lanes and left instead to tangle with traffic congestion.

“If you look at the numbers from a transportation perspective, they just do not look very good at all,” said Jeff Brown, chair of Florida State University’s Department of Urban & Regional Planning.

Gabe Klein, former transportation director in both Chicago and Washington, D.C., is an ardent streetcar supporter. He doesn’t buy the idea that they’re ineffective just because they mix with traffic.

“The argument you hear is that streetcars aren’t fast enough,” Klein said. “Guess what? It doesn’t matter.”

Making a beeline for the Gold Line

The Gold Line is Charlotte’s first foray into the modern-era of American streetcars.

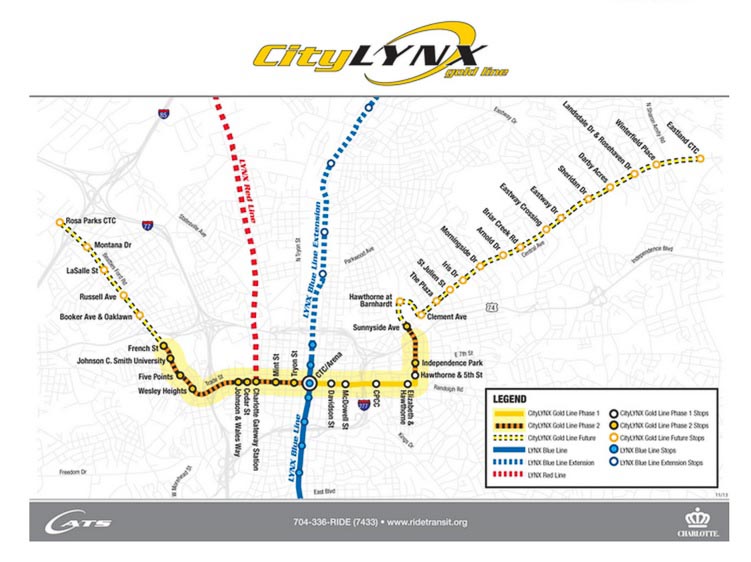

It’s a roughly $37 million project, mostly from federal sources, that connects to the city’s light rail system and runs through the city’s central business district, including stops at major destinations like Presbyterian Hospital, Central Piedmont Community College and the Time Warner Cable Arena.

Its cars run with 15-minute headways during peak periods and 20-minute headways the rest of the day. That puts it just barely within the commonly accepted standards for transit service frequency that allows risers to arrive without knowing the schedule ahead of time.

Eventually, though, it’s envisioned as a piece of a 10-mile line and the primary east-west transit corridor in the city.

Planners are forecasting average daily ridership of about 1,100 riders for the abbreviated downtown spur.

“It’s our toe in the door,” said John Mryzgod, a transit services project manager with the City of Charlotte. “It’s only a mile and a half, so it’s hard to serve a large population right now.”

The next phase, he said, is when the Gold Line is expected to become a major factor in the city’s transportation system.

A streetcar boom and a research aftershock

A few years ago, Brown, the Florida State professor, and some of his doctoral students started to look into streetcars and found there was very little research on the topic. Memphis opened its streetcar line – the first in decades – in 1993. Then Portland opened its line in 2001.

Recently, though, cities began jumping into streetcar projects, but there just wasn’t much evidence to say whether they were good or bad investments.

In the last two years, that’s begun to change as more lines opened, data started coming in and academics began to take a closer look at the issue.

Brown has conducted several studies, including one slated to published in the Transportation Research Record, that examine the performance of lines in Little Rock, Memphis, Portland, Seattle and Tampa Bay.

Portland was far and away the most successful line, with a ridership more than twice that of its next-best peer. It also has the best level of service and is considered one of the most cost-effective. Its 16,000 riders per day dwarf the 400 daily riders in Little Rock, for instance. In Charlotte, planners think its full line could eventually attract 11,000 daily riders.

The reason Portland’s project has been so successful, Brown found, is that it was primarily conceived as a transportation option. Those in other cities were primarily conceived as economic development tools and tourism attractions.

Streetcars have been largely promoted by visitors’ bureaus and downtown groups, not transit advocates, he found.

“The streetcar has been a lot like stadiums and convention centers, and it’s the same interests making those arguments,” he said. “It’s remarkable how similar they are.”

And the evidence that streetcars are even effective as an economic development tool is thin too, said David Levinson, professor in civil engineering at the University of Minnesota.

“Economic development investment is too strong a word for streetcars,” he said. “They’re a gadget. A toy. Economic development people think they’re a good investment – but they’re spending other people’s money.”

Charlotte’s new line has, indeed, been pitched along these lines. A city economic study suggested it could drive 1.1 million square feet of new development, including 730 new homes, and nearly 300,000 square feet of office and retail space, while eventually providing between $4.7 million and $7 million in annual tax revenue.

Yonah Freemark, manager of Chicago’s nonprofit Metropolitan Planning Council, emphasized that the evidence supporting streetcars as a sound economic development engine is weak.

The key distinction, he said, is that there’s little evidence a streetcar investment is any more effective than investing in a park, an improved streetscape, or just direct business incentives.

“What has been shown is that access to jobs (and) reduction in vehicle use – those do improve if people are given effective transportation options,” Freemark said.

“The way transportation influences development,” Brown said, “is by the efficient movement of people and goods.”

Stuck in traffic

A key point of emphasis among all the academic skeptics of the modern streetcar projects is that there isn’t anything inherently wrong with streetcars. The problem is with the way they’re executed. Cities tend to build streetcar systems so that they share travel lanes with normal automobile traffic.

That, of course, isn’t always the case. Freemark pointed to many lines in Europe, as well as those in Boston and New Orleans, that segregate streetcars into their own lanes.

They tend to have avoided the same criticisms he and others have leveled at the country’s newer streetcar projects.

“The newer projects are not about moving people quickly and efficiently, or even safely for that matter,” Levinson said. “They’re about providing a photogenic mode of transportation. But that’s not to say you couldn’t have a streetcar that’s useful. Just take it out of mixed traffic. Europe does this.”

Is faster really better?

Klein, who worked directly on the long-delayed D.C. streetcar project, tires of arguments about removing streetcars from traffic to make them faster.

“This argument about what’s faster, I just don’t care,” he said. “No one is going to go faster than the pace of traffic anyway. What people miss is that above ground transportation in cities isn’t really about speed, and it never has been. It’s about connectivity and great places. What people want is reliability.”

More important, he says, is creating a place that people want to be, that links outdoor places, pedestrian needs, and transportation needs. If it’s pleasant and reliable, people will use it, even if it isn’t fast. And streetcars can be that project, he said.

He points to an experience he had in D.C. with an elderly couple that lived near Washington’s forthcoming streetcar line.

The couple was excited about the streetcar project. They had watched their neighbors leave the neighborhood in the 1960s, after the city’s previous streetcar system had been removed in 1962, and believed that’s why they split. When the streetcar was removed, they felt abandoned, they told Klein. They were promised the bus would be more flexible, but it didn’t feel the same. They knew the streetcar line. It felt permanent. Losing it contributed to the feeling that the city was falling apart.

“What people miss is that intuition without data is not very worthwhile,” Klein said. “But data without intuition can be worthless.”

Reacting to constraints

Both Brown and Levinson attribute the boom in streetcar projects, at least to some extent, to the creation of the Federal Transit Administration’s Small Starts grant program, launched in 2007. It makes federal money available to projects with a total cost below $250 million, a sum vastly smaller than fixed light-rail projects that typically get money from FTA’s New Starts program.

As those funds became available, cities started looking into projects that fit those restrictions.

Freemark, though, says cities are simply pursuing the projects they want and then reacting to local constraints.

“The biggest fight by far is a political fight about how space on the street is used, and this is the same with bus rapid transit,” he said. “If cities don’t want to take lanes away from cars and move them to transit, you end up with a streetcar.”

Klein likewise pointed to those local political constraints.

It’s a common story. A project is rolled out – either a streetcar or a “gold standard” BRT with a dedicated right of way. After the city begins negotiating with opponents, it gets watered down until it’s something else entirely.

“It’s not a streetcar issue,” Klein said. “If everyone has input, you end up with something that doesn’t mean much.”