Note: A version of this editorial originally appeared in the Houston Chronicle.

Researchers at Brown University have tracked all state takeovers across the nation since 1988, when the very first takeovers occurred, and they find no evidence that they lead to academic improvements.

Instead, they find evidence of lower test scores immediately after the takeover, followed by a period of about five years before returning to pre-takeover levels.

In addition, they find that takeovers are significantly more likely to occur in districts with higher concentrations of low-income learners and students of color; districts that have a larger charter school sector; and districts in states with a Republican governor as well as states with the same party controlling the executive branch and both chambers of the legislature. In particular, researchers find that districts serving larger concentrations of Black students are more likely to experience a takeover — regardless of academic performance.

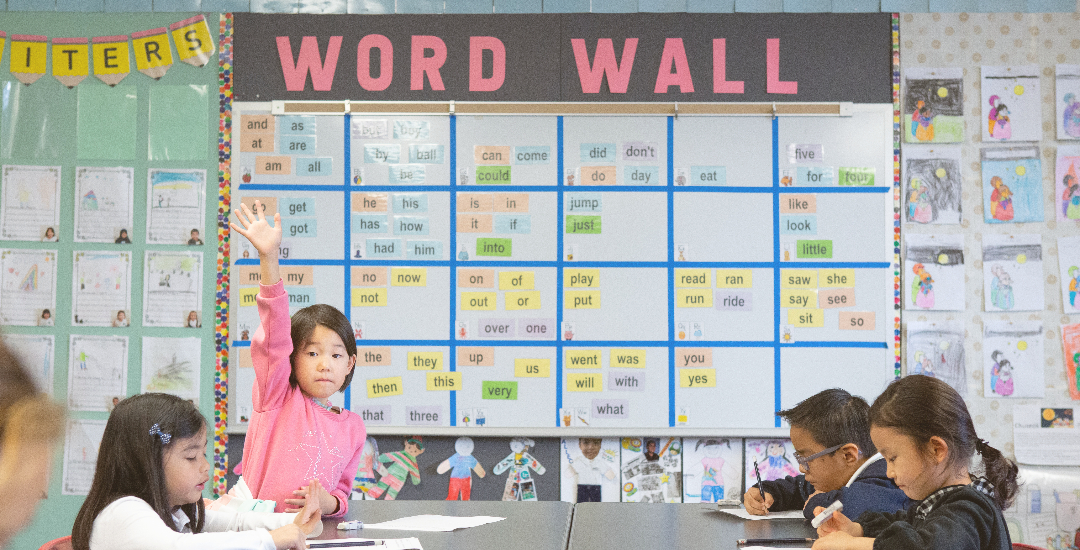

While there is no research evidence that state takeovers improve academic outcomes, there is substantial evidence that states can improve academic performance by increasing per pupil spending — which, we’d argue, should be referred to as per pupil investing. In general, states that spend more per pupil have better average academic performance.

Texas spent $10,342 per pupil in the 2020 fiscal year — more than $3,000 less than the national average. In Houston ISD, that number was even lower: only $9,380 per pupil.

School funding isn’t the only factor in students’ performance, of course. It will surprise no one that a comparison of about 450 million test scores from all public school districts in the nation shows that test scores are highly correlated with the socioeconomic status of each district’s families.

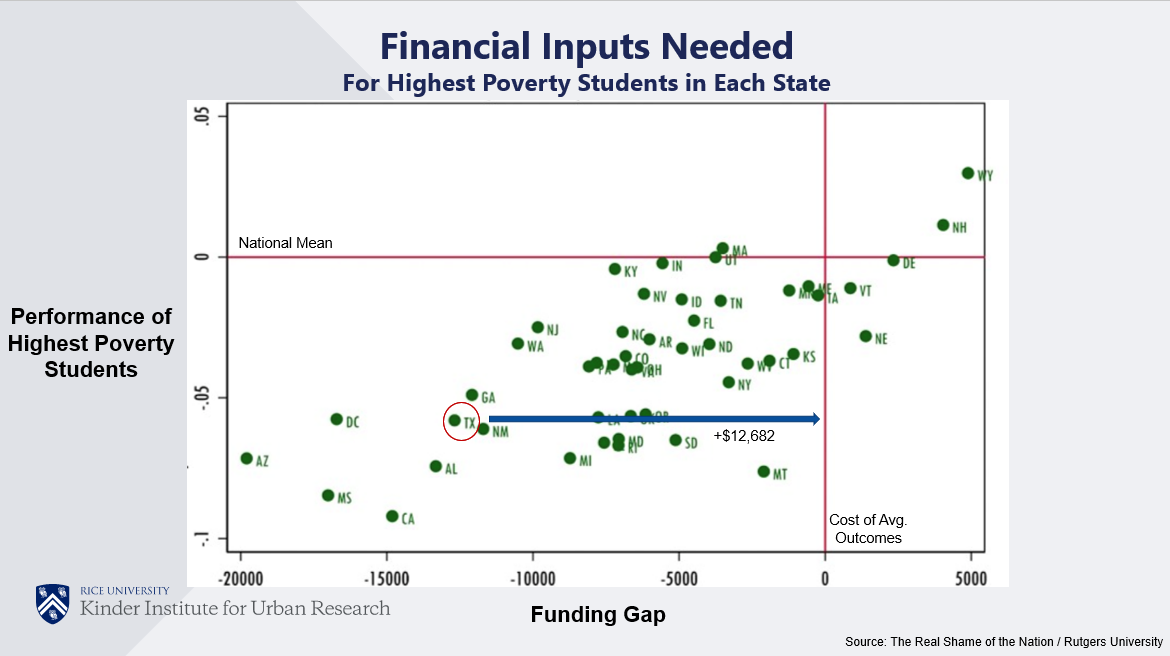

Using a complex model, in their report “The Real Shame of the Nation,” Rutgers University researchers calculated what it would cost to bring the average test scores of the poorest 20 percent of students in each state up to the current national average.

Low-income students perform worse in states with larger spending gaps — states whose actual spending is furthest from the amount needed. But in states with no spending gaps, poor students perform at or above the national average for all U.S. students — which shows that states can improve the academic performance of even our poorest students by investing more.

As you can see in the graph, Texas is among the states with the largest spending gaps. To bring Texas’ poorest students’ performance up to the national average, the researchers calculated that we’d need to spend $12,682 more each year on every Texas student.

That spending gap shows in Texas students’ performance.

School funding and poverty, of course, aren't the only factors that determine students' performance.

Some districts perform better than expected, given their socioeconomic status, and this is the case for HISD’s Black and Hispanic students. Although Hispanic and Black students in HISD perform below the national average — equivalent to about 0.6 and 1.3 grade levels lower — they are performing better than similarly poor Black and Hispanic students across the nation.

In conclusion, based on the research, it’s clear that a state takeover of HISD is likely to do more harm than good. The best way for the state to help improve the academic performance of HISD students is not through a state takeover but through a significantly larger financial investment.