On March 16 of last year, the bars were closed and restaurants were limited to take-out and drive-through service in Houston and Harris County. A few days later, public schools in Texas were closed. A stay-at-order was issued for Harris County on March 24, and on April 2, a statewide stay-at-home mandate went into effect.

Texans could still go to the grocery store, the pharmacy, the doctor and the bank. But they couldn’t go to the gym or barber, or get a tattoo, massage, piercing or drink at the bar. Outdoor exercise was still OK, as long as social distances were kept, and people — Houstonians included — responded in a big way.

Soon, parks were packed with walkers, runners and folks on bikes. In neighborhoods, there were fewer cars on the streets and more people. Many of them, for the first time, were getting out and discovering their own postage stamp of soil. And like Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, they found it was worth exploring.

This phenomenon wasn’t unique to Houston, of course. In cities across the U.S., people were finding respite — if only briefly — from their homes, the stress of their jobs or jobs they recently lost, the nonstop news and the endless updates on the mounting tally of COVID-19 cases and deaths, by stepping out the front door.

There was a dramatic increase in the popularity of walking and biking, and in response, city planners did what was done by many small and large businesses, as well as scientists, doctors, researchers and government agencies at all levels: they pivoted. Cities moved quickly to create more space for people eager to get outside during lockdowns, as well as frontline workers who didn’t have cars but did have concerns about risks related to public transit, and needed to get to work. They did this by implementing emergency measures such as temporary bike lanes, free bikeshare and street closures. New York, Portland, Oregon, and Boston were among places where segments of roadways were closed to vehicle traffic early in the pandemic.

Other cities — most notably, Oakland — opted to limit traffic on select streets, as opposed to closing them down completely, through “slow streets” initiatives. In Oakland, which launched its slow streets plan last April, 74 miles of the city’s streets — about 10% — were closed to through traffic.

Over the summer, the City of Houston launched its own “slow streets” pilot project in the East End neighborhood of Eastwood. From June 10 till Labor Day, portions of McKinney Street — from Milby Street to Dumble Street — and Dumble Street — from Polk Street to Harrisburg Boulevard — were closed to through traffic. The experiment was an effort to limit traffic and slow speeds on those residential streets by discouraging cut-through drivers, most of whom are trying to get to Harrisburg, Lockwood Drive and Polk Street — larger arterials designed for moving traffic faster.

What is a slow street?

A slow street is not a closed street. They are open to emergency vehicles like police cars, ambulances and fire trucks, as well as delivery vehicles and residential traffic. Slow streets projects take a tactical urbanism approach to slowing vehicles and making walking and biking safer. In Eastwood, temporary traffic barricades with signage reading “road closed to thru traffic” were placed at key intersections along McKinney and Dumble to restrict those streets to local traffic only.

Slow street restrictions, however, aren’t enforced because that would require paying law enforcement to do the enforcing — something strapped cities can’t afford during the pandemic. The shoestring budget for the Eastwood project didn’t allow for that either, and adherence was dependent on the honor system.

“This is more of a suggestion than something strictly regulatory,” explained Peter Eccles, a transportation planner in Houston’s Planning and Development Department. “If people pass through the barricades, they’re free to (do so).”

Instead, the barricades were intended to encourage drivers to consider taking a different route, such as a nearby thoroughfare, as well as reduce speeding by drivers.

“It’s meant to be a cue to them that this is a shared space with people walking and biking, and to be especially attentive as they’re driving,” Eccles said when he and David Fields, the city’s chief transportation planner, presented the findings from the three-month pilot project at the Eastwood Civic Association’s meeting in October.

If that happened, Dumble and McKinney would provide a safer route for people on bikes, pedestrians and others. A calmed McKinney would also offer residents of Eastwood and Greater Eastwood a safer crossing at the street’s intersection with Lockwood, along with safer access to Eastwood Park and a wide esplanade on Park Drive (just south of McKinney) that is used as a neighborhood green space, via the Dumble slow street. The McKinney-Dumble corridor also connected to the Harrisburg hike-and-bike trail, just north of Harrisburg.

Why McKinney and Dumble?

Eccles explained the criteria considered in choosing streets for the pilot project:

The streets needed to link parks and trails.

They needed to have readily available alternate routes for drivers who didn’t live in the neighborhood. (Polk, Harrisburg and Lockwood all provide alternatives for drivers who are just traveling through the neighborhood.)

They also wanted to make sure the project wouldn’t impact Metro services, and there are no bus routes on Dumble or McKinney.

There had also been complaints from residents of the neighborhood about speeding and cut-through traffic.

In recent years, and increasingly during the pandemic, a major contributor to traffic in the Eastwood neighborhood has been a steady flow of Amazon delivery trucks coming and going from the site of the Harrisburg Art Museum at the corner of Harrisburg and Eastwood Street. The location acts as an overnight docking station for the trucks, which, each morning, make their way to Amazon’s distribution center at Ernestine and Munger to be loaded with deliveries. Most of the Amazon drivers use Harrisburg to access Lockwood and reach the distribution center. However, some of the drivers choose to use residential streets, heading south on Eastwood, then east on McKinney to Lockwood.

According to Paul O’Sullivan, who lives in the neighborhood, McKinney Street residents have complained that traffic speeds have increased to nearly 50 mph in the years since Amazon came to the neighborhood. The “slow streets” barricades, he said, helped steer some of the delivery truck traffic back to Harrisburg.

“So, Eastwood seemed like a great candidate,” Eccles said. “We didn’t think that it was the only neighborhood in the city that could have benefited from something like this, but as we were looking around for a small network, with only a few barricades, this rose to the top as a pretty good candidate.”

Reaction to slow streets was mixed

Feedback on the slow streets project was collected by phone and email, and in part by monitoring reactions on social media. Eccles said the city also wanted to gauge the impact, if any, the project had on traffic volume on either street.

While some residents offered support for the slow streets pilot, citing it reduced cut-through traffic and made biking and walking safer and more comfortable for children on Dumble and McKinney, much of the feedback was a mix, ranging from strict opposition to confusion. Some of the residents who were opposed claimed the slow streets were inconvenient to drivers, while others thought it was a misuse of time and money. Eccles said he thought the latter was simply a misconception, emphasizing the project was cost neutral: “This did not cost any additional money from the city,” he said. “It was all (done using) existing supplies and materials. And the staff time that we took on this was by no means the equivalent of another staff position or something like that.”

Some residents reported the project made them feel excluded from their own neighborhood, that the barricades seemed to be “walling off a certain section in the neighborhood.”

This response and other comments found in threads about the slow streets project on the neighborhood social media app Nextdoor indicate there was a lot of confusion, as well as some misinformation, surrounding the initiative.

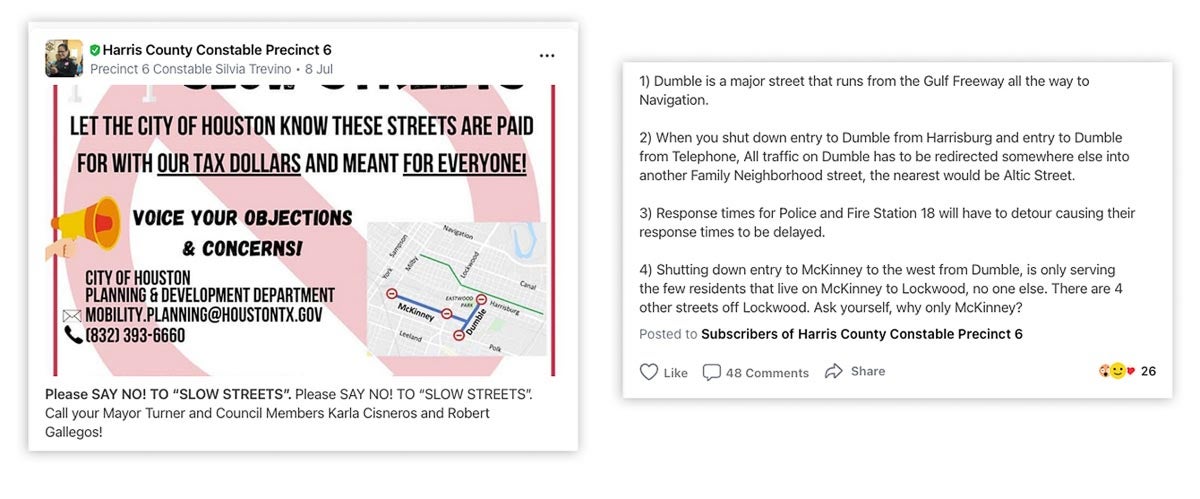

In July, Harris County Precinct 6 Constable Silvia Trevino spoke out against the project in a Nextdoor post from the Harris County Constable Precinct 6’s account, encouraging residents to oppose the effort:

“Please SAY NO! TO ‘SLOW STREETS’. Call your Mayor Turner and Council Members Karla Cisneros and Robert Gallegos!”

“Let the City of Houston know these streets are paid for with our tax dollars and meant for everyone!”

Trevino included erroneous information in her post, such as claims that Dumble is a “major” street and that law enforcement and fire trucks would be delayed in responding to calls because they wouldn’t be permitted to use Dumble and McKinney.

“Whether intentionally or not, the selected streets for this program in Eastwood are the streets where the homes have higher property values, thus restricting access to other residents in the surrounding Eastwood area. If the goal is to make these streets more pedestrian and cyclist friendly for everyone, then they should consider ideas like street bumps and stop signs, and not an idea that only benefits a select few.”

The following comments were among those left in response to Trevino’s post:

“Seems that the privileged people who can afford to stay home are benefiting over those who need to come and go. I don’t mean to offend anyone but the execution and motivation behind this are ‘Things that make you go ‘Hmm’”

►►►

“Who’s idea was this? Some fancy person who complained about not being able to ride their bicycle in our neighborhood? Some of us need to leave the neighborhood each day for work and necessities. All of us who live here now have trouble getting in.”

►►►

“The streets have been there for generations. If someone wants to create their own private community they should have moved to one.”

(In response)

“Straight up! Interesting how most of these changes have happened only in the last year or so. Our neighborhood was just fine all of these years before. What changed?”

(In response)

“I have lived in this neighborhood for 20 years. The average rate of speed in our neighborhood is what has changed, nay increased from 30 to 35 miles an hour to 45 to 55 miles per hour; that is what has changed. Any effort to lower that average speed is to be appreciated.”

Communication is key to understanding

In other cities, including Oakland, the quick implementation of car-restricted slow streets was met with similar resistance from some residents.

“Sometimes people in marginalized communities are very caught off guard by what is seen as priority,” Aidil Ortiz, a program manager at a social justice nonprofit in Durham, North Carolina, told Citylab. “I knew if slow streets were implemented without dialogue and consent and co-ownership, people would resent how it unfolded, and it’d become another example of how some people matter and others don’t.”

When communities encounter changes like the slow streets project, especially in neighborhoods that are experiencing rapid shifts or are vulnerable to gentrification, suspicion often is the response. Many times, these also are neighborhoods whose residents have voiced concerns about the speed of traffic where they’ve lived for years, but nothing has been done. Community engagement and communication are necessary to create awareness and secure buy-in for projects such as slow streets.

In 2019, when Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, in partnership with the Third Ward-based Sankofa Research Institute, conducted a comprehensive needs assessment to support the development of strategies, policies and investments in the historically Black neighborhood, the research team adopted a community-based, participatory approach to collect data about the strengths and struggles of the community. After the survey was completed, the Kinder Institute’s Houston Community Data Connections (HCDC) team joined the initiative to help disseminate the findings, build the capacity of nonprofit organizations to understand the data and empower community members to use the data to advance community priorities.

To do this, the HCDC team collected feedback and suggestions from community organizations to create an online tool to visualize shareable data collected from close to 1,300 households in the three census tracts north of Alabama Street. They also held several workshops to promote awareness and understanding of the needs-assessment data. Finally, when the results of the assessment were ready to be shared, the team used an interactive Data Walk to engage residents and stakeholders in dialogue about the findings. It was a long, involved and inclusive process that required time and funding.

In the case of the slow streets project in Eastwood, planners were working to act fast in reaction to the pandemic by quickly — and inexpensively — making room for more than cars on McKinney and Dumble. Unfortunately, the quick rollout of the project didn’t allow time for building the awareness and understanding needed.

Lesson learned for future slow streets

Eccles and Fields told the Eastside Civic Association that the main takeaways from the three-month pilot project included the need to better communicate the “what and the why” of slow streets. There might have been more support for the project if the fact that it was about improving the experience for people walking and biking — and indicating the streets are a shared space — had been more clearly communicated.

They also learned they needed to engage more with the residents and neighborhoods affected by the project; not only Eastwood, but also the area immediately surrounding Eastwood. In particular, the residents to the east of Dumble Street, which, they said, “is a pretty important connection for people traveling from Telephone Road up to Harrisburg.”

While the slow streets project is over in Eastwood, there are plans to continue the program in Houston. Residents in other areas of the city have expressed interest in bringing slow streets to their neighborhoods. Eccles said the program is being further refined by incorporating the lessons learned in Eastwood. That includes improving the communication and community engagement strategy for the project, as well as “leaning on the neighborhoods and the residents themselves to champion these projects.” Going forward, the plan is to create an opportunity for neighborhoods to sponsor and apply for slow streets projects.

“We think that slow streets is a very promising tool for general traffic safety,” Eccles said. “The city has a number of tools in its toolkit that range in cost, as well as the amount of engagement and lead time that they require. And (slow streets) was up really in a matter of weeks. So, there’s a major advantage to slow streets in that respect. But we do want to better contextualize slow streets within that larger toolkit.”