Over the past two years, we have been studying Houston-area students who are classified as English learners, or ELs—students who have a home language other than English, such as Spanish. We defined a subset of this population as long-term English learners, or LTELs, when students are not reclassified as English-proficient after five years in school.

LTELs represent a rapidly growing and increasingly vulnerable segment of the Texas student population. Between the 2000-01 and 2014-15 school years, the percentage of first graders who began school as ELs increased slightly. In contrast, the share of these students who became LTELs increased by almost 90%. In recent years, as many as two-thirds of all English learners in Texas became long-term English learners—meaning the majority of English learners who begin school in Texas are not deemed proficient in English before they start middle school.

English learners who become proficient early in their schooling go on to achieve academic success similar to if not better than native English speakers. On the other hand, English learners who take five or more years to become English proficient and continue into middle school as long-term English learners are at risk for academic difficulties in middle school and high school.

In our most recent research, we found that as early as eighth grade, these long-term English learners are placed on an academic trajectory that makes it less likely that they will graduate high school on time and attend college.

We found that LTELs who did not reclassify as proficient before entering middle school fall behind by as much as two years in reading and math skills compared to their peers who reclassified in elementary school.

Not surprisingly, we also found that LTELs who did not reclassify before high school were 60% less likely to take Algebra 1 in middle school, a marker of being ready for advanced coursework heading into high school.

The data also show that delayed English proficiency was associated with increased absenteeism and more exclusionary disciplinary actions, such as suspension, expulsion or placement in an alternative school program. Both are clear indicators of withdrawn student engagement.

Ultimately, the longer it takes for a student to be considered English proficient by their school, the more likely they are to drop out. In fact, English learners who did not reclassify as proficient before high school were 40% more likely to drop out than those who were able to reclassify in elementary school.

All of these things have consequences for their success into adulthood and represent a dire inequity in our school system with potentially profound multigenerational effects.

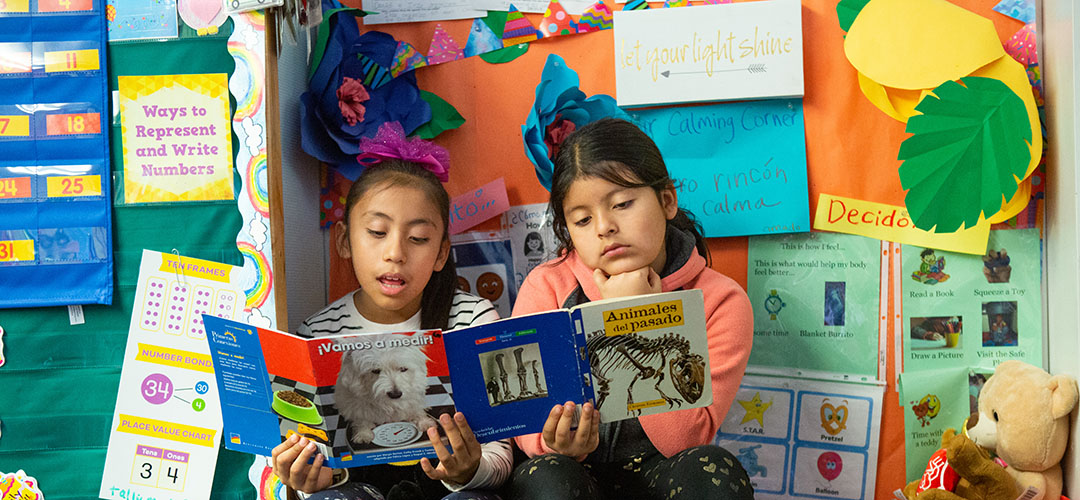

English learners in Texas public schools need more support. Our research has shown that dual-language instruction, where students learn both English and their home language, is effective for fostering English language development. Continuity in language instruction is also extremely important. In the Houston area, three out of every four students who changed through multiple language programs in elementary school were likely to become long-term English learners.

Students who continue into middle school and high school without testing as proficient will need continued support for their English language development. They should also have access to the academic support and coursework they need to set them up for success in high school and beyond.

At home, parents are encouraged to continue using the student’s home language, as research has shown that this also supports English language development. In addition to support at home, parents should reach out to their children’s teachers and schools to better understand how their schools are preparing their students to become English proficient.

Finally, parents should ask their schools about the English language assessment that their students will take in the spring semester, such as when it is, what is on it, and how they can prepare for it. This assessment is critical in a school's decision about whether or not a student is considered English proficient and can be a gatekeeper to being reclassified as English proficient.

While the risks of delaying proficiency are thoroughly documented in our recent report, the opposite circumstance—having English learners become proficient within their first five years—comes with a number of advantages. English learners who reclassify as proficient in elementary school are just as successful, if not more, than their native English-speaking peers.

Notably, the state of Texas no longer calls these students “English learners”—instead, they are considered emergent bilinguals, a recognition of how being bilingual or multilingual is a strength that these students are uniquely suited to build. The more we can do to support them, the more our entire region stands to gain.