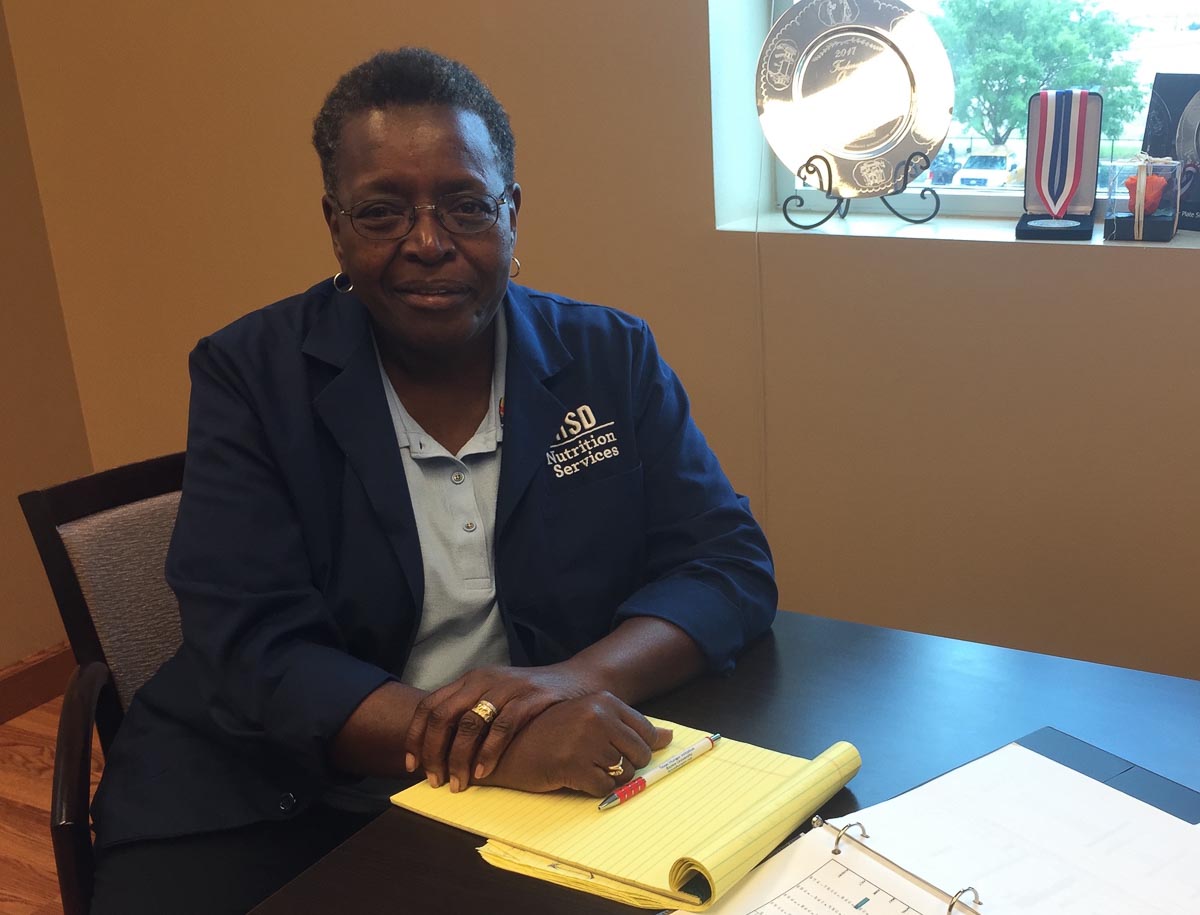

Betti Wiggins' arrival in the Houston Independent School District as the new officer of nutrition services has been hotly anticipated. "Houston Parents, Rejoice! Betti Wiggins Is Coming to Houston ISD," read the April headline on the blog The Lunch Tray. Local news welcomed the award-winning Rebel Lunch Lady who remade Detroit public school's food system. But in an interview a couple weeks before the start of school in Houston, Wiggins isn't shy about the fact that she might generate some conflict before her mission of making the city's school food healthier is complete.

"There's a culture of fresh fruits and vegetables in this state but there's also a culture of a lot of fat," said Wiggins. "One of the biggest obstacles here now is competitive foods. We've got restaurants and booster clubs [in the schools]."

Houston is, in many ways, a perplexing place to fly the food justice banner. Compared to Michigan, the growing season here is substantially longer: 10 months compared to six, according to Wiggins. And there are several assets specific to Houston that could help boost the cause: from groups like Hope Farms or Plant It Forward Farms to large institutions like the Texas Medical Center or the University of Houston's Center for Urban Agriculture and Sustainability. But even with the blessings of the natural environment, local food is still somewhat of a novelty and regular farmers markets in Houston are not as plentiful or accessible as those in other big cities.

"There's a lot of stuff happening out here," said Wiggins on her early impressions of Houston, "but I don't see a cohesive collaborative approach to decreasing or eliminating or solving the problem of food equity in this city. I'm being nice in calling it food equity," she adds, "but it's about food justice."

Wiggins grew up on a farm in a Polish community in Michigan, dreading April when the children would have to head to the fields and help plant that year's crops. She remembers fondly the rows of okra, corn and tomatoes in her mother's garden.

Those months cultivating food stayed with her in college when she was drawn to the Black Panthers, in part, because of their breakfast program for children and it shaped her understanding of hunger and poverty when she helped conduct research in a 10-state study, documenting diet histories of vulnerable populations, that later helped launch the federal breakfast program in schools as well as programs to help feed the elderly.

"To me," she said, "food is not a privilege. It's a civil right." And she sees public schools as ground zero for protecting that right.

In Detroit, after a career in community healthcare, she made a name for herself revolutionizing how and what public schools students ate. She cut ties with the school district's food management company, got rid of the chicken nuggets and hot dogs and introduced salads and whole wheat bread. It came with a cost, of course. "Before Wiggins came on board, DPS was spending 23 percent of its budget on food; it’s now 51 percent," wrote Civil Eats. In addition to shaking up the menus, Wiggins started a school garden program with more muscle than the typical modest patch of green. According to Civil Eats:

The largest DPS farm is located at the Drew Transition Center, a school for young adults with special needs. There, a 2-1/4-acre farm and 96-square-foot hoop house produce corn, greens, and root vegetables. More than 7,000 ears of corn from the Drew farm ended up on the plates of schoolchildren throughout Detroit last year.

Her work has earned her a list of accolades including the 2017 Silver Plate Award from the International Foodservice Manufacturers Association.

When Wiggins looks at the Houston schools, she says she's already seen areas of potential conflict, from making sure every school has access to healthy food to curbing the proliferation of off-menu food for sale inside the schools from booster clubs and other sources.

"One of the things I hope to do here in Houston is to ensure and affirm that the food from our poorest school to our richest school, on that steam line, is the same," she said.

But that might mean that parents in some schools have less of a say than they've had in the past. "The biggest challenge is to change the parents. The parents pay for what they got," she said.

And because fresher, more locally-sourced food items will likely mean pricier menus, Wiggins said there may be fewer options available a given meal. "Parents entrust me to take care of their kids," she said, "But I'm not running a damn Luby's."

It's a shift in thinking that has to happen across the board, from HISD employees to parents and kids. "I'm trying to convince people right now," said Wiggins, "I am not running a commercial program; I am running a nutrition program."