Some of the proposed plans for the highway are quite dramatic, like removing the Pierce Elevated; building greenspaces atop capped sections of downtown freeways; and creating massive new interchanges for parallel freeways that mix managed lanes, main lanes, and frontage roads to reach -- in at least one section -- 30+ lanes across.

While these visions might appear to be the product of a sleep-deprived highway engineer’s late-night inspiration, there’s more to them than that. They’re a mashup of urbanist desires—highway teardowns and connective greenspaces—with the realities of living in a sprawling metropolitan area that use massive new highways to confront traffic.

They are, in fact, just a few of the many changes the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) is proposing for a rebuilt I-45 and downtown highway system in Houston. The current project, which has been in the planning stages for more than a decade, intends to give a serious facelift to I-45 from Beltway 8 through downtown.

TxDOT should be applauded for its bold vision for the future of Houston’s highway network and for its engagement with residents in the process. Over the past 10 years, thousands of Houstonians have weighed in on what they would like to see happen in the I-45 corridor. More than 1,000 pages of public comments have been collected since 2011.

Given the fact that major infrastructure will be in place for decades after its construction, public feedback is crucial to helping TxDOT make choices about future projects. In the case of I-45 plans, input and continued engineering refinement led TxDOT away from bizarre ideas for tunneling express lanes below city streets.

A new role for roads

TxDOT’s proposed plans importantly move the agency away from its traditional approach to improving urban highways: widening and decking existing roads. While many such projects, like the building of express and HOV lanes, have proven successful in Houston, building ever-larger freeways is not a durable solution for either financial or sustainability reasons. Innovative solutions, such as those proposed for I-45, offer the chance to envision a new future for Houston’s mobility network.

The entire plan is impressive. But the downtown portion of the plan—which consists of removing the Pierce Elevated from I-10 to U.S. 59/I-69 and rerouting I-45 to run parallel to first I-10 and then U.S. 59/I-69—is easily among the most ambitious and innovative aspects of any TxDOT proposal to date.

If completed as currently sketched out, the changes downtown would not only substantially improve traffic congestion, they would remake central Houston’s built environment.

Removing the Pierce Elevated eliminates an unsightly boundary between downtown and midtown. Capping options would create massive new greenspaces north of I-10 at North Main and east of the George R. Brown Convention Center. Much like Kyle Warren Park in Dallas or the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway in Boston, these areas would offer room for a variety of innovative amenities.

The downtown greenspace would build upon the civic energy created by Discovery Green, BBVA Stadium, and the Toyota Center, and connect the East End with downtown. They would also mesh aesthetically with the proposed land bridges for Memorial Park. By building these spaces, the city could create an entire system of over-highway parks and recapture prime spaces now given solely to cars.

The historical vision for roadways

While the vision offered by TxDOT is certainly new, Houstonians themselves have been imagining how the city’s highways might better serve the daily life of the city for decades.

In fact, the Pierce Elevated has been at the center of those imaginings since its conception in the 1950s and construction in the 1960s. During the planning stage for the roadway, city leaders hoped the Pierce would frame the city’s booming growth by offering views of the burgeoning skyline. On opening day of the roadway, leaders happily trumpeted the “magnificent view of the business district,” that the road gave. With its elevated position, they claimed, the driving experience was “almost like going up in a cable car.”

But others saw in its hulking presence an injury to a city on the rise. In a Texas Architect article from 1966, critic Patrick Horsburgh called the space beneath the elevated “psychologically intolerable” and doubted that any real form of urban life could occur beneath it.

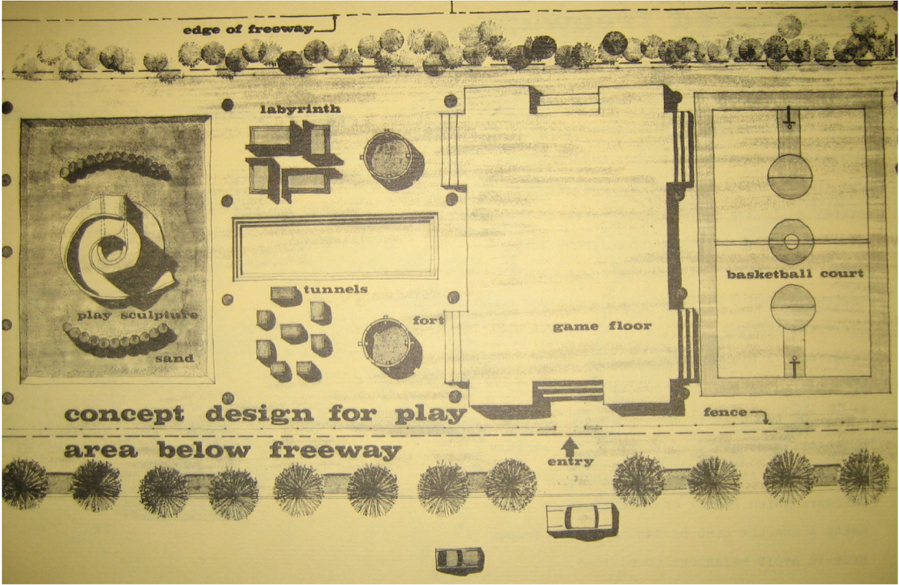

In response to Horsburgh and complaints from nearby residents and businesses about the drabness of the overhead roadway, the city tasked the Houston Arts Commission with envisioning other possibilities for the space beneath the Pierce. After studying the 1.3 mile long, half-block wide area, the commission concluded that the space was ideal for “playgrounds, plazas, and parking” and included a number of illustrations depicting children playing basketball and office workers enjoying a break beneath six lanes of traffic.

City of Houston Department of Planning, “Beautification Study: Freeways,” 1968, Box 5, City of Houston Planning Department Collection, RG A 004, Houston Metropolitan Research Center.

While the artist’s renderings made playing basketball and eating lunch underneath a highway seem possible, if not downright enjoyable, only the parking element of their vision came to pass. For the last 40 years, parking has been the only major use of the spaces beneath the downtown highway.

The idea of tearing down the elevated, though, has already motivated several new ideas about what to do with the decommissioned roadway. Several groups have begun campaigns to turn it into Houston’s version of the famed High Line in New York City. These advocates offer some compelling rationales. An elevated park would continue Houston’s push to create more publically accessible recreational spaces and would certainly add character to downtown’s built environment.

Houston needs more than just green spaces

But might maintaining the entirety of the elevated structure and repurposing it as park limit the potential for other possibilities?

What if we used the existing superstructure from Buffalo Bayou to Bagby Street to make an elevated park? This could connect two green jewels—the bayou park with Houston’s first complete green street. It could carry pedestrians from the bayou path to midtown, give sweeping views of the skyline and bayou system, and keep foot traffic away from the “parkways” offered by the current TxDOT plan.

Using only a segment of the Pierce for an elevated park would leave nearly four-fifth of a mile of land to develop in other ways. If coupled with the purchase of other parcels, public and private developers might remake the whole length of the current route.

This could include public spaces such as ground level linear parks, public squares (without a highway overhead), and other mixed-use developments. Such options could take advantage of proximity to the Red Line light rail and continue Midtown Houston’s transit-oriented redevelopment. State-owned land could be used to build much-needed affordable housing in close proximity to downtown. And all this work would directly reconnect downtown and midtown by removing the physical barrier of the Pierce.

We have a long time to discuss options. The final choice on the overall highway plan and the Pierce Elevated decision are years off. But the chance to have conversations about what we as Houstonians want out of the system and its individual pieces presents us with an exciting opportunity. We at the Kinder Institute are looking forward to participating in those discussions. Let’s all keep on imagining what our new mobility system and our city might look like in the decades to come.

1“A New, Beautiful Freeway Link,” Houston Chronicle, August 22, 1967, H-Freeways-1950s Vertical File, Houston Metropolitan Research Center (HMRC).

2Patrick Horsbrugh, “Blight, A Foretold Affliction,” Texas Architect, May 1966, Folder 3, Box 29, George Fuermann Collection, Special Collections Library of the University of Houston, 7-8.

3Houston Municipal Art Commission; City of Houston Department of Planning, “Beautification Study: Freeways,” 1968, Box 5, City of Houston Planning Department Collection, RG A 004, HMRC.