As a millennial from suburban Raleigh, North Carolina, I cannot deny having grown up in an era where public transit came second to the automobile. Despite this, I realize now that I’ve actually taken for granted the relative safety of the cities I previously called home. From the pedestrian-oriented streets of Montreal and New York to the well-maintained sidewalks and greenways of Raleigh, I’ve lived a peaceful coexistence as a pedestrian in a world full of cars. My most recent move to Houston, unfortunately, introduced me to the rigor of car-oriented streets.

When I first arrived in America’s fourth largest city, I was initially struck by the seemingly endless maze of freeways, feeders and surface roads that envelope and define the city and its neighborhoods. As an urban planner, my internalized bias suggested I oppose the city’s blatant auto-centricity. And yet, I’ll admit, I found I was drawn to and impressed by the network’s apparent efficiency.

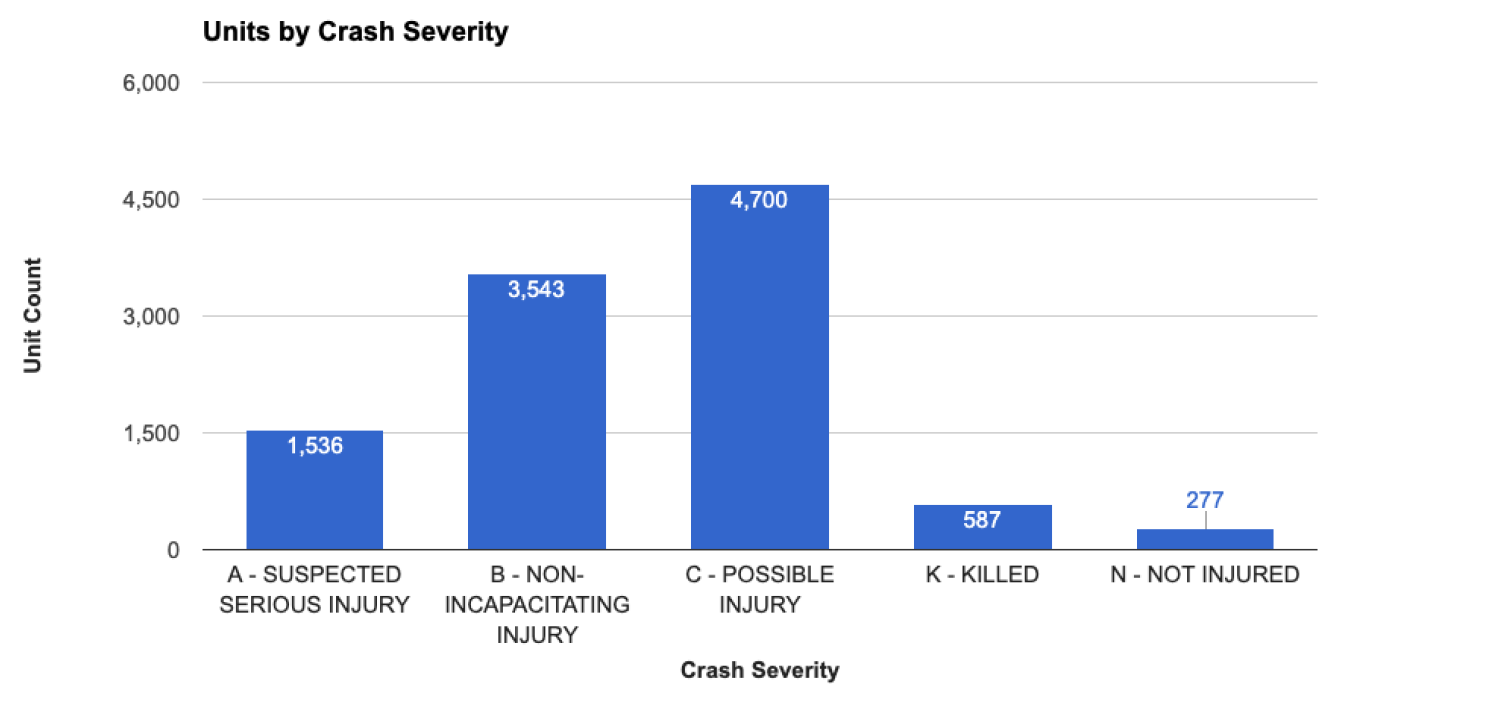

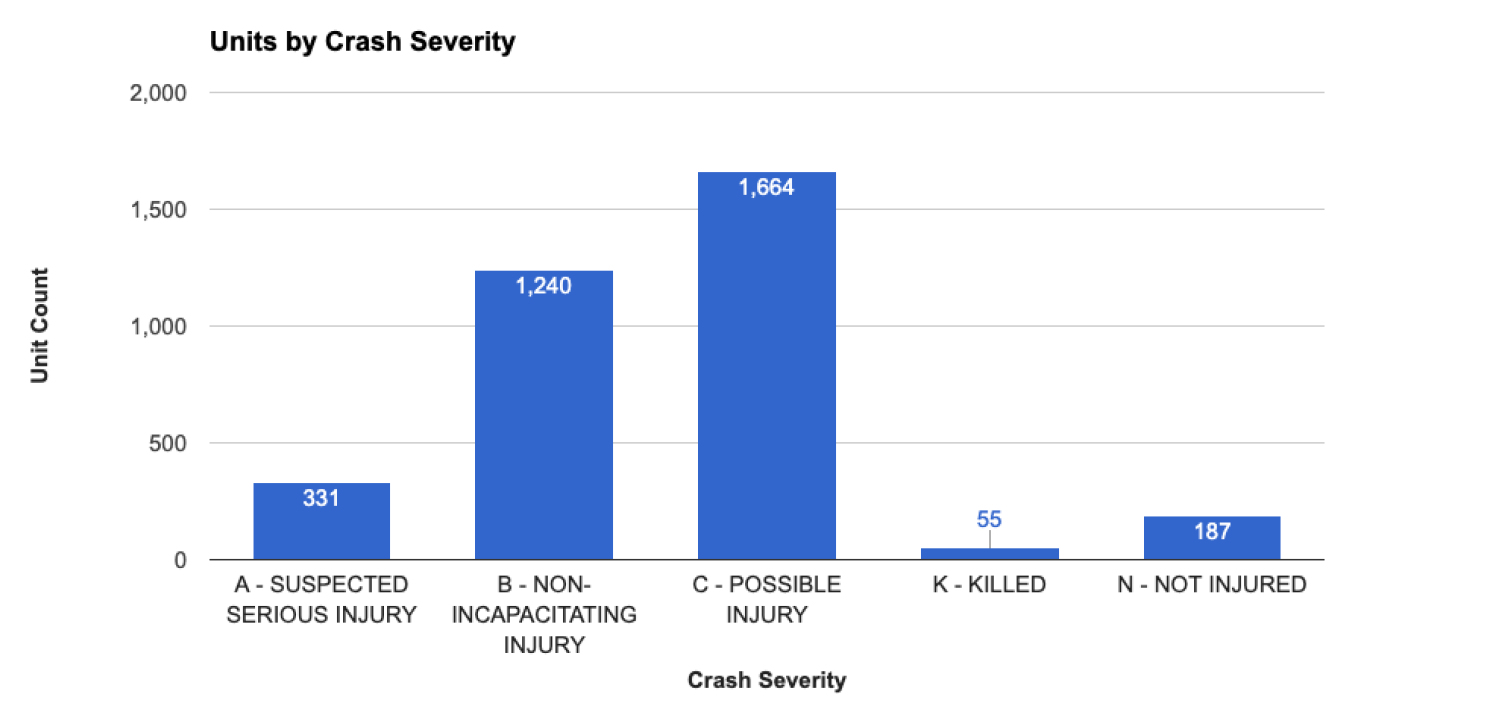

I soon realized that while this vast network benefits commuters, it does little to safeguard pedestrians and cyclists, including myself. According to data published on the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT)’s Crash Records Information System (C.R.I.S.), between 2010 and 2018, 10,643 pedestrians and 3,477 cyclists were struck on Houston’s roads. Of those, 587 pedestrians and 55 cyclists died. This past month, I came close to adding myself to these stats.

A total of 10,647 pedestrian-related crashes occurred on Houston's streets from 2010 to 2018. Of those, 587 people were killed. Source: Texas Department of Public Transportation

A total of 3,477 cyclist-related crashes occurred on Houston's streets from 2010 to 2018. Of those, 55 people were killed. Source: Texas Department of Public Transportation

Where I live in Midtown, near the intersection of Elgin/Westheimer and Smith Street, is particularly difficult and unsafe to navigate. Since moving into my apartment at the end of November 2018, TxDOT has recorded thirteen crashes at this intersection. Understandably, I rarely bother crossing this intersection.

For work, I commute to our office in the Texas Medical Center via light rail, cautiously crossing the highly-trafficked intersection at University and Main--known for its own share of pedestrian and cyclist incidents. For the past six months, I’ve traveled this route to work, walked my dog around the neighborhood, and even ventured to the grocery store on foot, without incident.

My false sense of safety came to an abrupt end one Friday morning last month. While walking my dog along our normal route, I attempted to cross a street just outside the apartment, assuming that the car halfway down the block noticed us crossing.

Big mistake.

Before I knew it, the driver, rolling through a stop sign, pushed us into Smith Street. Fortunately, I held my dog’s leash on the opposite side of where the car hit me and the driver (who apologized profusely shortly after realizing what happened) was not accelerating at full speed. We survived, slightly traumatized but mostly unscathed.

Admittedly, it’s easy to forget that behind TxDOT’s stats there are actual people — our friends, parents, siblings and children. Personal experiences do much to awaken this reality, as it did for me. But, given that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration consistently ranks Houston in the top five metro areas in the U.S. for roadway fatalities, it’s a reality that the city must acknowledge and work to address.

Does Houston want to be known as a city unsafe to those outside of cars? As a society, we have grown accustomed to accepting traffic fatalities as a result of modern urban life. But in actuality, most deaths could be avoided with simple street design interventions, heightened traffic enforcement, and improved driver awareness.

Before the automobile, city streets served two vital functions in the American city: they provided vibrant, public space for social and commercial activity to flourish and they facilitated traffic as corridors intermingling various modes of transportation, including pedestrians. After a century of car-centered development, Houston’s streets mimic those of a racetrack: wide, fast-flowing, facing minimal obstruction. Streets are made for cars first, pedestrians and cyclists second, if at all.

Today, urban-planning schools, municipalities, and design firms are taking a new approach to street design. This approach seeks to revisit and build-upon the pre-automobile era where streets facilitated pedestrian activity alongside other forms of transportation. New Urbanism, the Complete Streets Movement, and Vision Zero are representative of this shift, emphasizing safety and activity above all else.

Aspects of each can be seen in neighborhoods throughout Houston today — though, notably, the City of Houston still lacks a Vision Zero Plan of its own. Neighborhoods such as Gulfton are receiving much deserved attention, thanks in part to the work the Kinder Institute has done. However, much is still needed to be done.

To start, simple interventions such as giving pedestrians a head start at busy intersections could do a lot to save lives. The city could also utilize raised crossings or road diets at heavily-trafficked intersections to slow down drivers and ensure pedestrian safety.

Doing nothing is not an option. Thus far in 2019, fifteen pedestrians and one cyclist have been killed in Houston. That’s sixteen deaths too many. It’s time the city takes a step toward creating a safer, pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly Houston.