While the nation’s unemployment rate continues to hover near a 50-year low of 3.6% — it’s right around 3.5% in both Texas (3.4%) and the Houston area (3.6%) — the current and long-term prospects for many U.S. workers are fairly bleak.

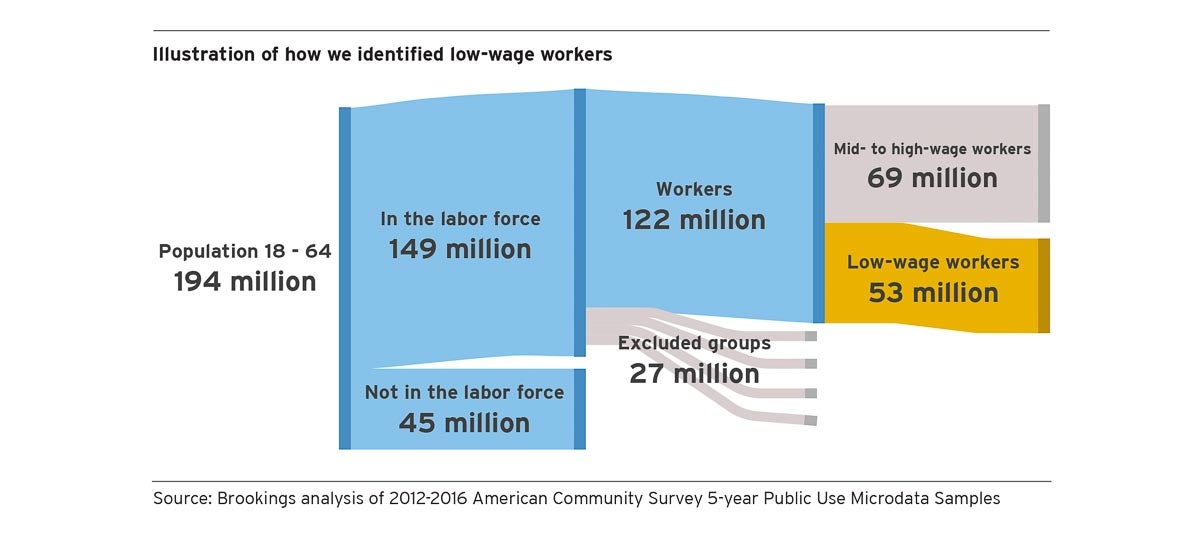

More than 53 million people — 44% of all workers between the ages of 18 and 64 — are in low-wage jobs earning median hourly wages of $10.22 and median annual incomes of $17,950, according to a recent report from the Brookings Institution.

Though the country’s ongoing high rate of employment is encouraging, the research reminds us not every job pays well and leads to long-term financial security. Ideally, low-wage jobs serve as entry-level opportunities for younger people with the potential to earn more as they gain experience and education. Unfortunately, for many with limited access to training opportunities and education, the reality is a life of low-wage employment, economic stagnation and hardship.

“We have the largest and longest expansion and job growth in modern history,” Marcela Escobari, co-author of the report, told a reporter with Bloomberg last month. “(That expansion) is showing up in very different ways to half of the worker population that finds itself unable to move.”

More education equals more pay

The researchers divided the 53 million low-wage workers — defined as those earning two-thirds of the national median hourly wage for men working full time and year-round — into nine groups based on age, education attained and school enrollment. The three age categories were 18-24, 25-50, and 51-64. Low-wage workers between the ages of 25 and 50, considered to be a person’s prime working years, with a high school diploma or less make up the largest segment — 28% — of the low-wage population. And close to 40% of low-wage workers are 25 to 64 years old with no education beyond high school.

“Given the importance of education in the labor market, this group of 27 million faces limited prospects for earnings growth,” cites the report.

A large amount of research has shown the direct relationship between educational attainment and earning potential, as well as the decrease in unemployment rates with more education.

In the 2017 book “Bridging the Gap: College Pathways to Career Success One,” the lifetime wage returns for those with associate degrees are estimated to be 22% higher than high school graduates. That increases to 32% for those with bachelor’s degrees, and 46% for graduate degrees.

Disproportions among low-wage workforce

Though the population of low-wage workers is racially diverse, discrimination and bias persist in the labor market, according to the report. Those with the least economic mobility and most likely to remain in low-wage jobs are women, people of color and those with low levels of education. Specifically, low-wage workers are 52% white, 25% Latino or Hispanic, 15% Black and 5% Asian American, but a disproportionate number — 54% — are women. And higher shares of Hispanic and Black workers — 63% and 54%, respectively — earn low wages compared to whites (36%).

Age is also a limiting factor in the economic mobility of these workers. Research has shown older workers (those over the age of 35) are less likely to advance out of low-wage jobs than younger workers. And the chance of moving to a higher-paying job shrinks the longer they are earning low wages.

Many low-wage workers are in a handful of occupations

Nearly half of low-wage workers are employed in just 10 occupations, according to the Brookings Institution report. The five occupational groups with the largest number of low-wage workers are retail salespeople (4.5 million), information and records clerks (2.9 million), cooks and food preparation workers (2.6 million), janitorial and pest control workers (2.5 million) and material moving workers (2.4 million).

The rest of the top 10 were food and beverage servers (2.4 million), construction trades workers (2.3 million), workers who dispatch and distribute material (1.9 million), motor vehicle operators (1.8 million) and other personal care and service workers (1.8 million).

In Houston, where there are around 1.2 million low-wage workers, roughly 38% of the workforce, the occupational groups with the lowest mean hourly wage are food preparation and services, building and grounds cleaning and maintenance, personal care and service, and farming, fishing and forestry, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

With higher wages comes a higher cost of living

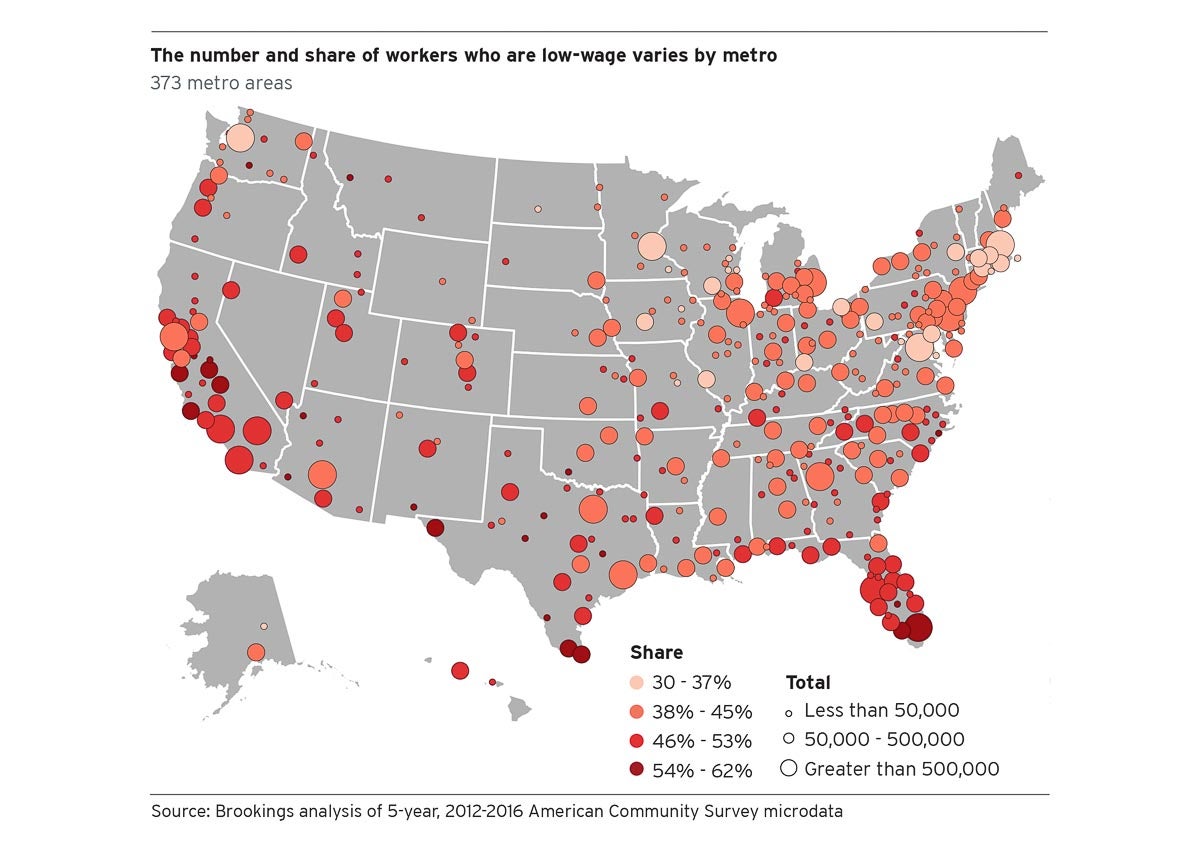

Houston and other large metros such as Miami, Los Angeles and New York have large populations of workers who earn low wages, but there are less populated areas in the southern and western U.S. where low-wage workers comprise higher percentages of the workforce. Cities with the largest shares are Las Cruces, New Mexico (62%), Jacksonville, North Carolina (62%), Visalia, California (58%), Yuma, Arizona (57%), and McAllen, Texas (56%). In these places, unemployment rates are higher and more jobs come from industries with low median wages such as agriculture, real estate and hospitality.

Regions of the country with concentrations of high-wage industries such as health care, professional services or finance create high-paying jobs that are filled by people with at least a bachelor’s degree. These areas have below-average shares of low-wage workers, according to the report.

Does that mean there are no retail or food service jobs in these places?

High-wage jobs in these regions have indirect economic impacts on local job growth and wages by “increasing demand for retail, food service, and entertainment,” the report shows. “One influential analysis highlighted high-tech jobs in particular as generating the strongest wage benefits for all workers.”

But how does this play out for workers in traditional low-wage occupations? Even with increased wages, can they afford the housing costs and the cost of living?

No, they probably can’t, according to the Brookings Institution report:

“The fact that fewer low-wage workers live in a place does not necessarily indicate a more inclusive economy, but rather that the occupational mix and housing prices favor those with college degrees and higher earnings. It may also reflect that low-wage workers are priced out of living in the region in which they work, and make long commutes from more affordable places. And for low-wage workers who remain in these high-cost areas, they may be limited to neighborhoods characterized by high levels of poverty, unemployment, and crime.”

What can be done to help workers advance?

Those who are trying — and most likely failing — to support themselves and their families on earnings from low-wage work are faced with economic uncertainty and, as time passes, the increasing inability to change their situation.

Some recommend better training programs and more education as the path to higher pay. However, others contend the strategy of educating workers out of low-wage jobs is useful but doesn’t do enough to address economic inequality. CityLab’s Richard Florida, for example, proposes upgrading and transforming service jobs in the same way manufacturing work was transformed under Franklin Roosevelt last century, when jobs in that industry went from low-paying and insecure to high-paying jobs that could support a family. Part of that upgrade is a minimum wage based on the cost of living in different geographic areas.

As the Brookings researchers point out, finding a good job that pays well requires skills and abilities but education and training alone aren’t enough. Getting a degree or certification won’t help if there are no jobs to land. Instead, they suggest rethinking approaches to workforce and economic development by working with area employers to teach skills tailor-made for the local job market and regional productivity, and to guide, counsel and support those working to improve their skills.

In Houston, initiatives such as UpSkill Houston are connecting employers with educational institutions, community organizations and government agencies in the region to help them create customized programs to teach workers the skills employers are seeking.

Aerospace industry experts, government leaders and entrepreneurs recently gathered in Houston for SpaceCom, where they discussed how to prepare the workforce of today and tomorrow to meet the needs of the expanding space economy. San Jacinto College is working with industry leaders to prepare workers for essential middle-skill careers such as cloud computing, data science and cybersecurity in the tech industry, which require advanced education and skills beyond high school, but less than a four-year college degree.

“You can get a certificate, you can get associates degree, or you can get a four-year degree, but how does that tie into the workforce and what is really needed?,” San Jacinto College District Chancellor Brenda Hellyer asked during a SpaceCom panel discussion. “With the work we are doing, we have to have those conversations with the workforce.”