As states begin to receive and distribute COVID-19 vaccinations, racial inequities are once again coming into focus. Vaccination data from across the United States tracked by the Kaiser Family Foundation illustrates that although they have represented a disproportionately high percentage of cases overall, non-white Americans have received a disproportionately low percentage of vaccines as of Jan. 31 of this year.

In Texas, people who identify as Hispanic or Latino have suffered 43% of all COVID-19 cases, yet have received only 16% of vaccinations. Black Texans represent 19% of all cases but only 7% of all vaccine recipients, while Asian residents represent 9% of all cases but only 1% of vaccine recipients.

In anticipation of these disparities, the National Academies of Medicine (NAM) was commissioned by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the fall of 2020 to formulate a framework for the equitable allocation of the vaccine. To mitigate health inequities, their report recommended that areas be prioritized in accordance with the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index.

Still, three months later, decisions on where to focus efforts through an equity lens has proven controversial. Last month, the Texas Tribune reported the Dallas County Commissioners Court voted to prioritize residents of 11 mostly Black and Latino ZIP codes based on increased vulnerability to the coronavirus. However, Dallas leaders reversed their decision after state health officials threatened to cut the city’s vaccine supply.

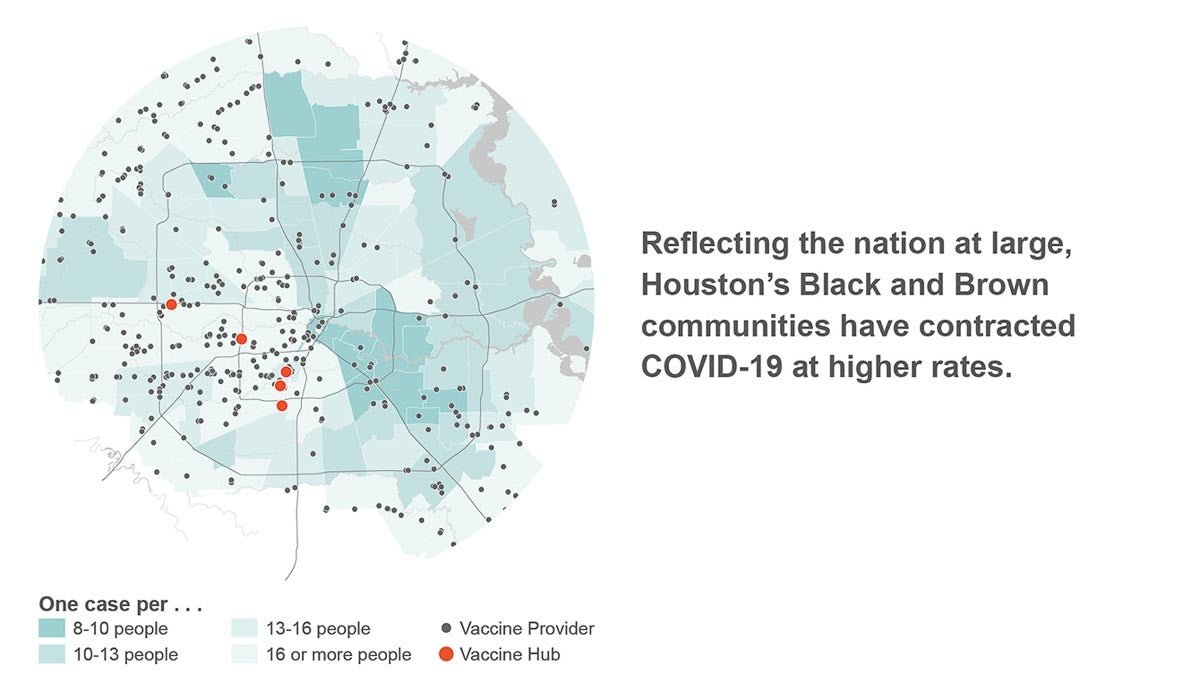

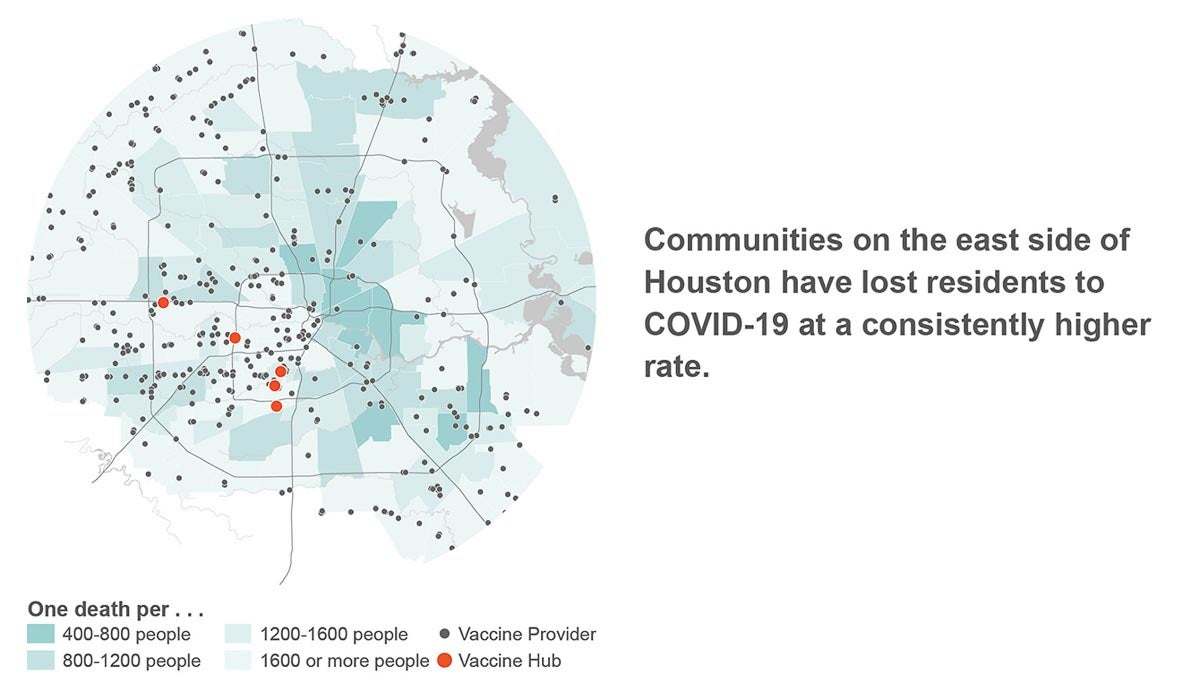

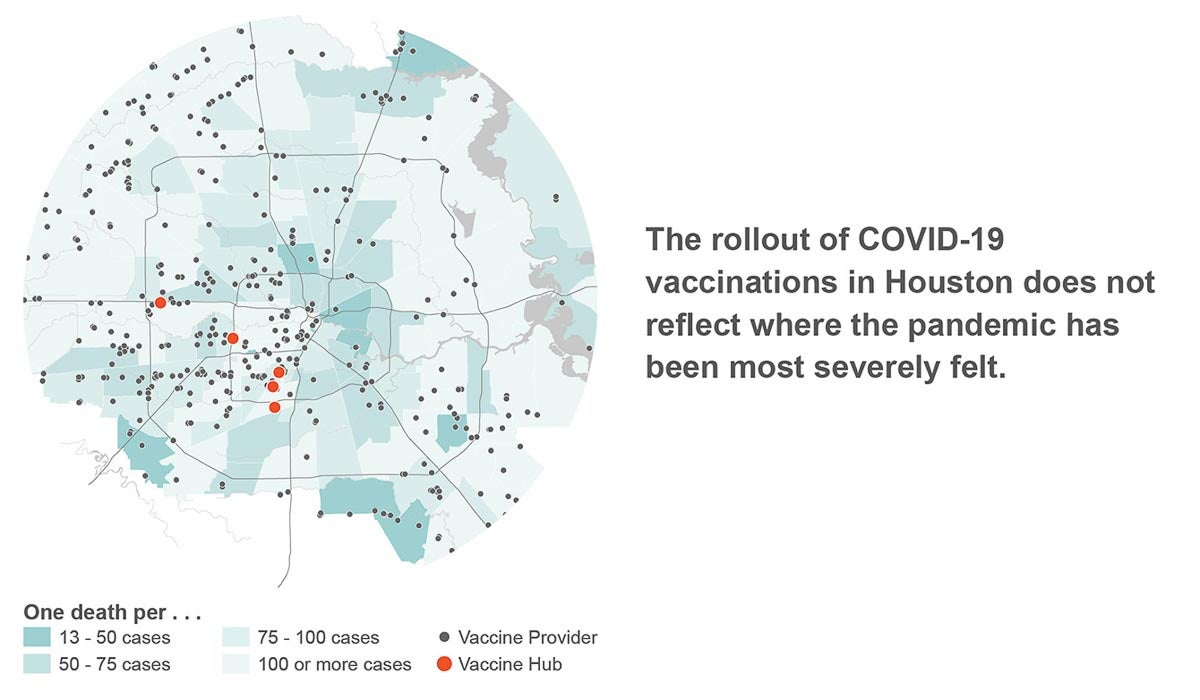

It is indisputable that the pandemic has exacerbated racial disparities in Houston, which is aggressively segregated. The majority of the city’s most vulnerable communities are located east of the I-45 corridor, while the majority of resources are concentrated in wealthier, whiter neighborhoods west of downtown. Reflecting the nation at large, Houston’s predominantly non-white communities have contracted COVID-19 at higher rates, and cases in these communities have been more likely to result in death. For example, in the majority-Hispanic neighborhood of Magnolia Park, one in every 400 residents has died as a result of COVID-19.

Data source: Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS), Harris County Public Health (data through Jan. 11, 2021)

Yet, the rollout of vaccinations has not reflected what we know. Vaccination sites are glaringly sparse in neighborhoods where the pandemic has been most severely felt, and instead are overwhelmingly located in the same westside neighborhoods as the rest of Houston’s resources.

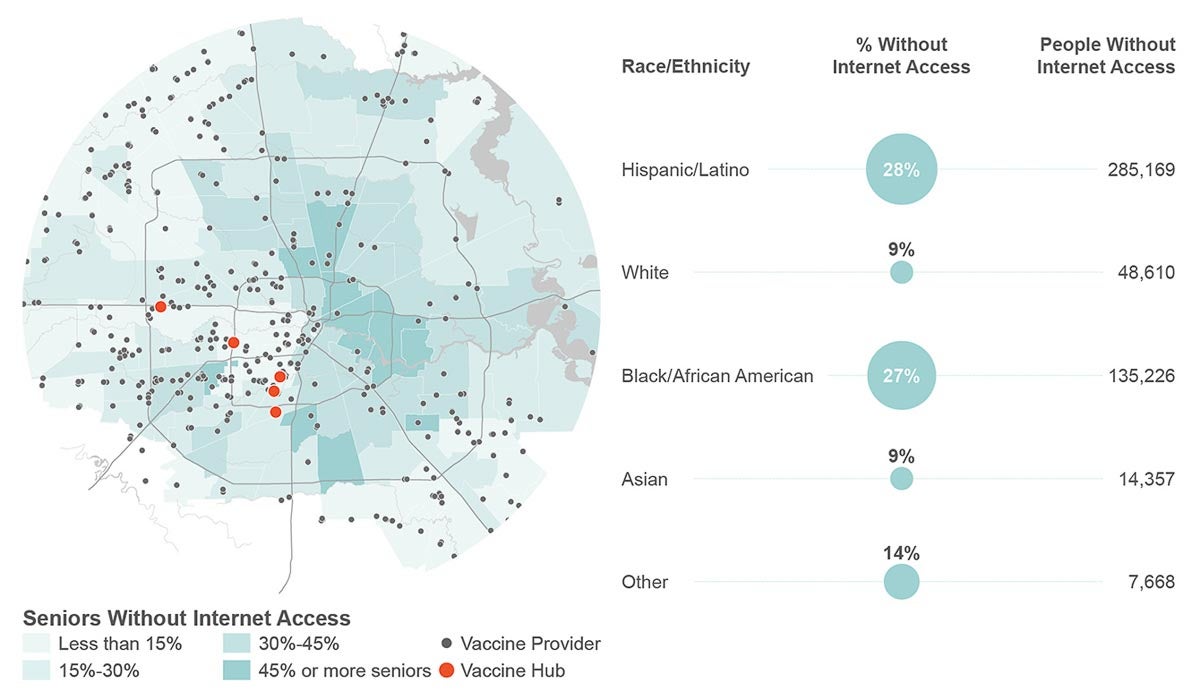

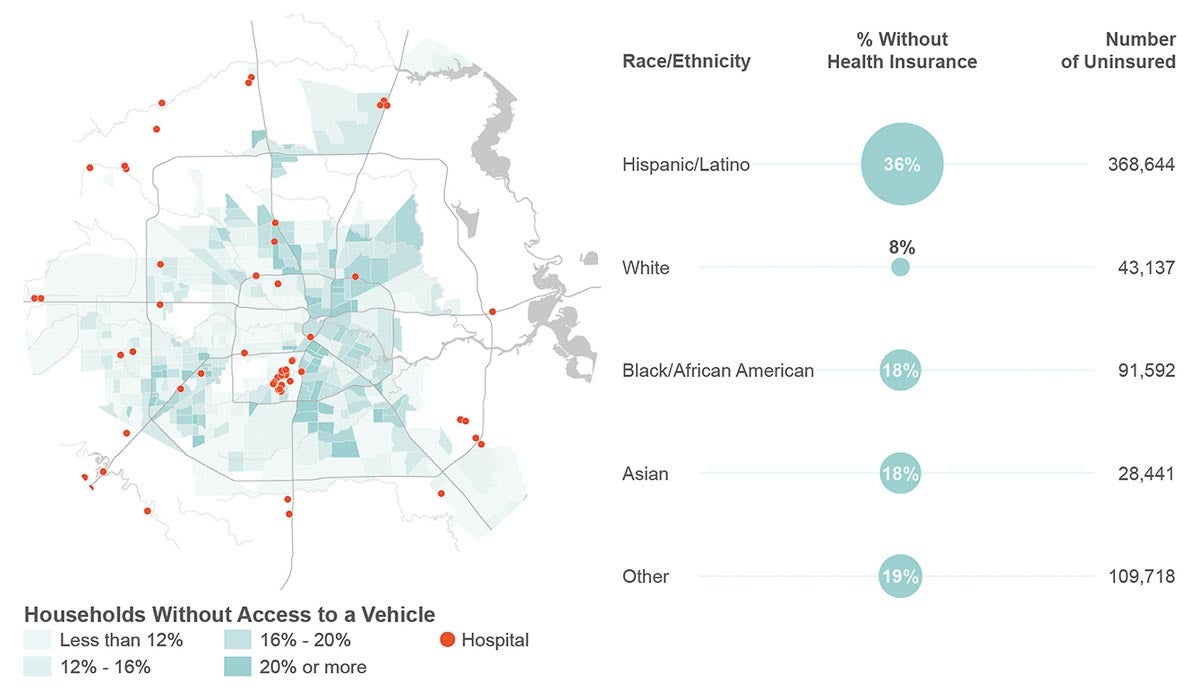

Further, lack of direct access to vaccination sites is magnified by existing intersections of privilege. Residents who do not live near a site are less likely to have the internet access needed to find one outside of their neighborhood and set up an appointment; they are less likely to have access to the transportation needed to make it to that appointment; and they are less likely to have the consistent health insurance coverage that would provide experience navigating the medical-industrial complex in general.

As vaccines proliferate, another — more qualitative — disparity has come into play: the privilege of having been cared for in the past. Established patients of area private hospitals, such as Houston Methodist, who qualify for the vaccine are receiving texts and calls instructing them on how to schedule a shot. For those without a provider, the barrage of information sent out by the City of Houston and Harris County has not made the path to vaccination clear. Information changes daily, sometimes by the hour, as did information on COVID-19 testing throughout 2020. Registration sites have crashed repeatedly, and too many people are already exhausted by nearly a year of suffering. Access to these ever-changing updates is also dependent on internet access, which is not universally available.

Census data from 2018 showed that more than 25% of Black and Hispanic households in Houston did not have access to the internet, while less than 10% of white households were not connected.

As the cards stack up against Houston’s most vulnerable residents, the historic exodus of health care facilities from under-resourced communities is starkly clear. Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital is the only hospital serving northeast Houston. In fact, hospitals, doctors’ offices, pharmacies and even grocery stores follow the same pattern of disinvestment as all other vital resources for survival in our city. So, even if the vaccine is in abundant enough supply to be delivered to every eligible health care site, the same message will be reflected back to us by nearly any data mapped: the consistent lack of care given to our Houston neighbors is pervasive and deadly.

Equity is not simply ensuring that the vaccine is available everywhere. There is increasing evidence that even when vaccination sites are set up in under-resourced communities of color, those showing up to get stuck are predominantly white. Rather, equity is understanding and addressing the layered barriers that keep hundreds of thousands of people from even knowing how, where or when to sign up for a vaccine.

There is a clear need for a national plan — one that’s informed by what we know about health inequities — to guide decisions at the state and local level and prevent the continued auto play of systemic racism. We cannot afford to tolerate opposition to prioritizing an ‘equity lens’ in decision-making. Threats such as those made by the State of Texas against Dallas leadership are in the most essential sense threats against residents’ very lives.

Whether or not people deserve to survive should not be broken down by ZIP code. For every person who has gotten the vaccine without qualifying under the requirements of either phase 1A or 1B, there is a Houstonian in urgent need without the tools to access their shot. Ask yourself why, systemically, those you know who have received the vaccination before their time have been able to do so, and whether that is evident of a city you would like to call home.

As humans, we cannot skip the line regardless of how special we think we are; we must all wait our turn with equal measures of patience and hope.

Susan Rogers is the Director of the Community Design Resource Center (CDRC) and an Associate Professor in the College of Architecture and Design at the University of Houston.

Katherine Polkinghorne is a research assistant at the CDRC and in her final year of studies.

José Mario López is a program manager at the CDRC and holds a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Houston.

Cynthia Cruz and Maria Noguera of the CDRC also contributed to the graphics.

Get Urban Edge updates

If you’re interested in stories that explore the critical challenges facing cities and urban areas — from transportation, mobility, housing and governance, to planning, public spaces, resilience and more — get the latest from the Urban Edge delivered to your inbox.