The past few months have been terrifying, but also cathartic. The pandemic has shaken most of us from a false sense of security about our individual health, the efficacy of our cities to provide a high quality of life, and forced us to question many of our daily habits — how we live, work, travel and exercise, as well as how we source the food we eat. Our connection to nature. The primary lesson we, once again, must learn is that cities are not divorced from nature. They are a part of the larger biome in which they’re located.

As planners and designers, we are trained to think holistically. While these fields of study promote cities as beneficial, no city is perfect — not even close, and the vulnerabilities and interconnections of the global supply chain has impacted all of us in unforeseen ways. In this post and others, I will delve into the benefits of reconnecting to basic processes that support our daily needs, such as the growing of plants for food, increasing equity in our local communities and local food security. I will look at models from the past that promoted urban gardens and gardeners, and show what worked and what did not. I will discuss the opportunities and challenges of being an urban gardener, what is needed to set up a garden of your own, and what laws and standards stand in the way of making cities better at promoting urban gardens.

Cities have always relied on their hinterland in order to exist. Through history, the roads, farms, woodlands and waterways that surround the city have had a symbiotic relationship with the urban center. The term ‘suburb’ is actually quite old; “Where dwelle ye, if it to telle be?” asks one of Chaucer’s pilgrims in “The Canterbury Tales.” “’In the suburbs of a toun,’ quod he.”

Medieval English suburbs grew from the urban center haphazardly, along the main roads leading to the town gates. The wealth resided in the town itself, the suburbs were ramshackle conurbations of informal settlements where the price of life was cheap. Accounts from the era paint a dire picture: “London, what are thy suburbs but licensed stewes?” asked one commentator in 1593, enraged by the prostitution, drunkenness and sloth located ‘next door to the magistrates’.

As the Industrial Revolution took hold in the 19th century, waterfronts and lowlands were sprawling, unregulated places made up of lay-by areas for raw materials, slums containing multitudes of workers, factories for production and warehouses with staging areas adjacent to ships and rail. The city, for most, was a dark, fetid place with social inequities, toxic air and water, overcrowding and rampant infectious disease. Disparity between rich and poor was extreme. Accounts from this time describe the poor working for employers who docked wages to pay for room and board, most often in squalid conditions. The system intended to punish the poor for their station in life.

These inequities became a serious concern when the general population was afflicted during the cholera outbreak of the 1850s. At first, it was thought that foul air in slum conditions was the cause (the Italian phrase for ‘bad air’ is literally ‘malaria’). Respiratory illnesses were associated with living close to factories belching smoke, and overcrowded, substandard housing was common. The outbreak was eventually found to be transmitted through unsafe water sources. As a result, modern sanitation and plumbing was the technology that became a change agent that made urban theorists rethink housing and ways of living for the working classes.

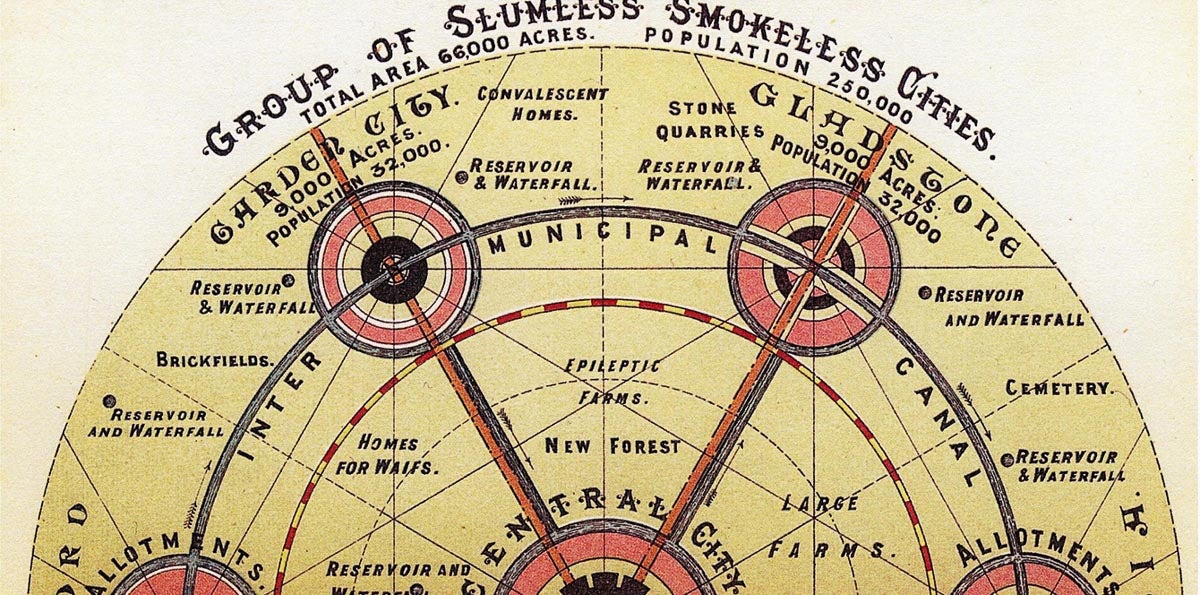

Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928) grew up in London, and his ideas became greatly impactful on the field of city planning. Howard saw the abuse of the poor as evidence of a society in crisis. More of a social theorist than a physical planner, he proposed a new way of living that predicted the self-determinative health and wellness movement in our society today. In his groundbreaking work “To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform,” he described and diagrammed a utopian city of the future.

In “To-Morrow,” he laid out his arguments, first describing what he called the “three magnets” — “town,” “country,” and “town-country.” He described the challenges of the industrial, modern city or “town” — the inequities, pollution and overcrowding aforementioned, as well as the shortcomings of living in the country, with its lack of access to resources to support economic growth. He then identified the benefits of blending “town” with “country.” The opportunities afforded by residing in “town-country” where people live in harmony with each other and nature while enjoying the benefits of immediate proximity to goods and services. He imagined a city where access to community and nature were one: “Human society and the beauty of nature are meant to be enjoyed together. The two magnets must be made one. As man and woman by their varied gifts and faculties supplement each other, so should town and country.”

Howard believed in investing in communities, and that they would be owned by trustees and leased to people who would not otherwise be able to get out of the overcrowded center city. Howard saw a city that would be structured around a close connection to the local neighborhood, where every action would contribute to the well-being of its residents. What he called ‘Garden Cities’ — compact urban districts ringing major cities — would be a place where families could live and work. They would be limited in size — roughly 30,000 people each — and connected to the center city by railway. These urban clusters would be surrounded by a green belt of agricultural uses, comprised of tidy neighborhoods of mixed uses, garden plots and walkable streets and spaces.

The neighborhood model could be expanded to endless scale; neighborhood clusters could be aggregated into what Howard called ‘Social Cities’ of 200,000 people or more. Some clusters could be linked together into what he called a ‘social city’ of six or more garden cities, interconnected by a transit system with ample agricultural lands in-between.

His work is often misunderstood as that of a ‘suburbanist’ only interested in creating what modern planners would call ‘sprawl,’ however, some of the neighborhoods he proposed would match center-city London of today. These densities are what we would call ‘middle scaled,’ with walkable cores and three- to four-story buildings on small blocks featuring a wide variety of urban housing prototypes, including live/work spaces and townhouses, apartments and condominium/flats, as well as semi-attached and detached housing types. There is a mixture of local businesses, services, retail food and beverage, institutional uses, and recreation. Within each neighborhood cluster is a central green space with trails and park connections into the countryside beyond. Importantly, every housing unit and most office spaces have a garden, or at least a view from a terrace onto a green space. Because he proposed tighter streets and larger blocks than were typical, Howard was able to dedicate more than half of the overall land area to open space and agricultural uses.

A number of Howard’s ideas were groundbreaking and ahead of their time; so much so that we have only recently begun incorporating them into city design. For example …

A profound interest in affordability

Howard was profoundly interested in affordability, where ownership of the land would be shared in a trust by the residents of the town, and not by developers and speculators. Individuals could work together to govern themselves with greater equity and fairness. To the degree possible, Howard hoped people would make and sell their own products and grow their own food. He was interested in creating a community of ‘makers’ tied to the land and localism … “rejecting the grosser trappings of industrialization … to return to a simpler life based on craft and community.”

Promoting entrepreneurialism

Howard believed in the power of the entrepreneurial spirit, and being sensitive to the prohibitive cost of starting a business, leased out the commercial lands of garden cities used for industry, orchards, offices and shops, as well as those used for owner-occupied cottages, limited-equity housing cooperatives, and rentals. He believed entrepreneurialism would be rewarded. With plenty of “field(s) for enterprise, (and) flow of capital,” places to live would be “bright homes and gardens, no smoke, no slums” … a sharing community — as opposed to a competitive one — would be found through “freedom (and) cooperation.”

He predicted what we might call ‘smart city’ technology today

The electrification of everything: “the smoke fiend is kept well (outside the) bounds of the garden city; for all machinery is driven by electric energy, with the result that the cost of electricity for lighting and other purposes is greatly reduced.”

He imagined an ecological city

Howard envisioned a “closed loop system” where the refuse of urban living is recycled or tilled into the land; “The refuse of the town is utilized on the agricultural portions of the estate, which are held by various individuals in large farms, small holdings, allotments, cow pastures, etc ….”

Howard’s ideas were revolutionary, but also immediately popular. Progressives in England were very interested in addressing the issues of inequity, and the working poor were excited for an opportunity to start a new life. Landowners in the central city saw it as an opportunity to redevelop land. In the ensuing decades, more than 30 garden cities were built.

Howard worked with notable planners, including Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker, and successfully created a number of ‘garden cities’ outside of London. Hampstead Garden Suburb, Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City, are all successful suburbs surrounding London. They could even be said to predate the “20-minute neighborhood” movement for which many in the planning community have recently espoused. All have access to transit, with local amenities and services within a close walk or bike ride. All promote local businesses and the ability to work from home.

However, there is one characteristic that distinguishes them from other examples of walkable, mixed-use communities. In all of these examples, the link between a resident and the land is a deep and abiding one. A leader of the Garden City of Hampstead Garden Suburban in England put it well: “We are just ordinary men and women …. Some read, some paint, some make music, but we all work … and we all garden … able to meet each other on the simpler and deeper grounds of common interests and shared aspirations.”

Garden cities in the US

The idea of creating neighborhoods closely connected to naturalized areas gained popularity in American city planning in the early part of the 20th century. Examples include Radburn, New Jersey, which was created by Clarence Stein and introduced the idea of the ‘neighborhood concept’ — predating the 20-minute-neighborhood idea in vogue today.

Forest Hills Gardens and Sunnyside Gardens, both in Queens, New York, the Village Green in Los Angeles, and other small examples in the U.S. share a common theme of streets providing access to individual housing units with private garden spaces that open onto shared community greens beyond. They all have strong codes, covenants and restrictions that promote collective decision-making and personal self-determination.

Wartime gardens

Gardens have also played a vital role in the preservation of our nation’s freedoms. During World War I, a severe food crisis emerged in Europe as agricultural workers were recruited into military service and farms were transformed into battlefields. As a result, the burden of feeding millions of starving people fell to the United States.

The National War Garden Commission encouraged Americans to contribute to the war effort by planting, fertilizing, harvesting and storing their own fruits and vegetables so that more food could be exported to our allies. Americans were encouraged to utilize any vacant land available that was not being used for agricultural production, including company property, school yards and vacant lots. Messaging of the importance of the effort was amplified by civic organizations, women’s clubs and public institutions. The initiative combined enlightened self-interest, human health, connection with nature and patriotism into one succinct story line.

Amateur gardeners were recruited as so-called ‘soldiers of the soil’ and encouraged to publish pamphlets about best practices for youth and the uninitiated. By the end of the war, home gardening had become a habit that most Americans retained.

In WWII, as transportation resources were redirected to the war effort and food was sent to troops overseas, domestic Americans were again encouraged to convert every open area available — including terraces, roof decks and flower boxes — into vegetable-producing gardens. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt converted the south lawn of the White house into a victory garden. Vegetables most often planted were beans, beets, cabbage, carrots, kale, kohlrabi, lettuce, peas, tomatoes, turnips, squash and Swiss chard. More than 20 million Americans participated in the effort, and their ‘victory gardens’ producing more than 40% of the total amount of fresh food consumed during the war.

Who controls the public realm?

Urban gardens were good for personal health, but they didn’t have a direct correlation with city planning until people like Ron Finley began the ‘Gangsta Gardening’ movement. Finley is impactful for planners because he called into question how streets are used and for whom. Working in South Central Los Angeles, Finley was fined by the city for planting a garden on land he owned that was determined to be a parkway (a utility strip between the sidewalk and street under city jurisdiction). He successfully changed the law in LA to allow the area between sidewalks and the street to be used by individuals for gardens. Through this act, he has inspired disadvantaged youth to take to gardening as an act of self-determination in the most hardscrabble conditions.

What this means for planning is clear: In the future, streets will not just as conduits for mobility and utilities, but also as places to restore the biome, grow food, purify the air and start a business. In Los Angeles County, where the land dedicated to surface parking exceeds more than 100 square miles, imagine how these areas could be put to better use in the future.

Administratively, it’s nice to see planners recognizing that urban living has much to do with making neighborhoods more flexible and high-performing in terms of food production. From a planning perspective, it still does not fully address the wasteful use of land in service of behaviors around convenience. What else can we do to accommodate gardening as a behavior integrated into our everyday lives and within our living spaces? As Ebenezer Howard wanted, how can we create a community of garden(ers) as much as gardens? What can be done to promote gardening as a part of managing and promoting our biome? In the next installment, I will delve into my own development as an urban gardener, what has worked and what has not. And what it can teach us as planners to promote more gardens and gardeners within our own neighborhoods.

Nate Cherry is a planning director for Gensler's Los Angeles-based Planning and Urban Design group. Gensler is a global architecture, design and planning firm.

The views, information or opinions expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research.