One of Houston’s greatest strengths and most important assets is its diversity. For years, that diversity has been growing, along with the population of the city and surrounding area.

The latest evidence being an analysis of diversity across five categories — household diversity, religious diversity, socioeconomic diversity, cultural diversity and economic diversity — in 501 of the largest U.S. cities. Houston did not rank No. 1 in any of those categories, but, overall, it is the most diverse city in America, according to the study.

Data and rankings such as these are useful, and news stories about them make for clickable headlines, depending on how high or low a city may find itself on any given list, but they aren’t able to portray how diversity plays out daily in a city like Houston. The fusion of cultures (which is often, and fittingly, thought of like a gumbo, but just as well could be a curry or caldo de res) isn’t something Houstonians are necessarily cognizant of every day, it’s more of an ever-evolving backdrop for life here. Bryan Washington is a writer and author — possibly the first — who captures that agglomeration and uses it as a set piece for his stories. He does so subtly, casually; it doesn’t feel forced — it’s genuine.

Here’s an example from his novel, “Memorial,” which takes place in Houston and Osaka and tracks the lives and relationships of Ben, a Black American, and Mike, a Japanese American. Here, Mike and Ben are having dinner with Mike’s mom, Mitsuko, at a “profoundly nondescript Tex-Mex restaurant around the block” from their apartment:

“By now, Mitsuko’s finished slicing up her meal. She’s also tanked her third margarita, fondling the lime beside it. Behind us, a quartet of teens has assembled in mariachi gear, settling into their stances to start in on a birthday tune. The woman they’re serenading beams beneath a hijab. Her friends sit alongside her, clapping as the teens strum along.”

Scenes like this and others in Washington’s work are instantly identifiable to Houston-area residents. Given the demographic trajectory of most of the U.S., Houston-level diversity will be the standard in the years to come.

The U.S.’s older population is growing rapidly, at a much faster rate than the younger population, which is seeing little to no growth. In the decade from 2010 to 2020, the population of seniors (age 65 and over) increased by nearly 40% and is projected to grow an additional 30% in the 2020s, according to a report from the Brookings Institution’s William Frey.

That trend holds for metropolitan Houston as well. From 2010 to 2018, the number of people ages 65 to 84 increased by half, while the number of people under the age of 20 grew by just 10%.

More importantly, Frey contends, is the fact that, among younger populations, the demographic gains will be from people of color — many of whom continue to grow up in families experiencing high levels of poverty.

“This means that the pipeline of future workers in our rapidly aging nation is growing modestly at best, and is made up of children among whom racial and ethnic inequality is amplified,” Frey writes. “For these reasons, the nation’s demography alone makes it imperative that the needs of children and young families are high on the policy priority list.”

Frey’s analysis shows an ongoing decline in the U.S.’s child population since 1960 when children (persons under age 18) accounted for 35.7% of the population. In 2020, children made up 22.1% of the population, and the downward trend is expected to continue, reaching a projected 20.6% in 2040.

When results of the 2020 census come out, Frey expects to see a small absolute decline in the number of children in the U.S. during the 2010–20 decade.

Thirty states had absolute declines in child populations between 2010 and 2019, with the largest decrease — 11.8% — in Vermont. Among the 20 states that saw increases, North Dakota’s 20.2% growth was the most significant percent change. The child population of Washington, D.C. went up 27.1%. In Texas, it there was a 7.8% increase. Declines in the populations of working-age adults (18–64) were experienced in 23 states. At the same time, the senior population (65 and over) increased in every state, as well as D.C., from as little as 22% in Iowa to as much as 67% in Alaska. In Texas, the senior population grew by 43.5%.

Fewer white children were born in 44 states during the 10 years, but in 15 of those states, growth in the children of color populations made up for declines in white children. That includes Texas, the state with the biggest numeric gain in children (534,000), where the number of white children declined by 15,708. At the same time, there were 518,278 more children of color in 2019 than there were in 2010.

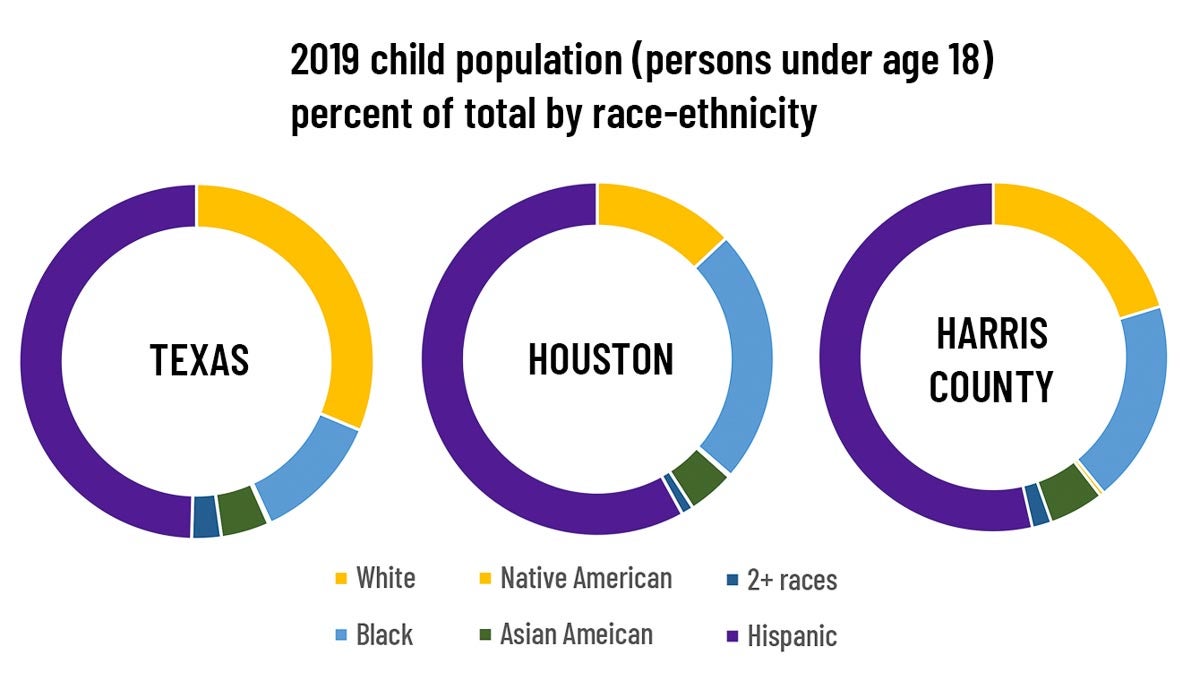

The statewide trends were mirrored in Harris County, which accounted for almost 18% of the increase in Texas’ child population (94,474). Of note is the decrease in white children seen in Harris County: 9,552 fewer white children in 2019 compared to 2010. That’s 61% of the state’s entire change in the white child population. Meanwhile, the populations of Black and Asian children in Harris County grew by 12,000 and 6,000, respectively, and most significantly in the Hispanic child population, which saw an increase of almost 75,000 children. Overall, 80% of Harris County residents who are under 18 years old are nonwhite; in Houston, it’s 87%.

Child poverty levels are highest in states where child populations aren’t growing, but, Frey points out in his report, they are higher than average in Texas and Florida — the two states that saw the greatest growth in child population from 2010 to 2019 (534,000 and 278,000, respectively). Hispanic populations made up the largest share of growth in both states. In Texas, the change in the number of Hispanic children (an increase of more than 342,000) was 64% of the state’s total increase in that group.

Not surprisingly, Frey also found significant disparities within the child poverty rates of each state. In Texas, the child poverty rate was 19% in 2019, but the rate varied among racial and ethnic groups, from 26% for Black and Hispanic children to 10% for Asian children and 8% for white children.

“These child poverty disparities represent the ‘starting point’ of a trajectory of racial and ethnic inequalities that have been evident among young adults in recent generations with respect to educational attainment, homeownership, wealth accumulation, and other measures,” Frey argues.

In his book, “Prophetic City: Houston on the Cusp of a Changing America,” Stephen Klineberg describes the convergence of two “fundamental transformations” economic inequalities based on access — or lack of access — to quality education, while, at the same time, the racial and ethnic makeup of the nation’s population is undergoing a dramatic change. “Nowhere,” Klineberg writes, “are these two trends more clearly seen or more sharply articulated than in Houston today.”

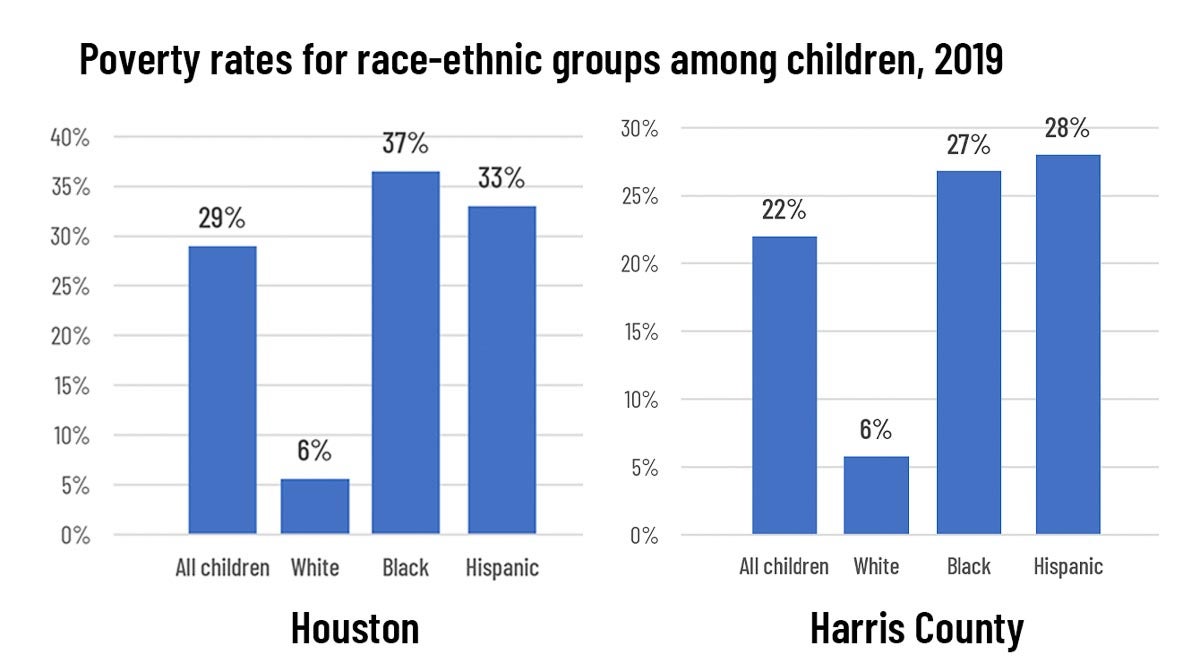

The “sharp economic divide by race and ethnicity within the child population” Frey found across the nation for African American and Hispanic children, the two largest nonwhite groups, hold for both Harris County and Houston.

Klineberg contends Houston is one of the nation’s most segregated cities, “not by ethnicity so much as by income.” A place where social services and schools are underfunded and neglected infrastructure — someone else’s problem. Without increased investment, there will be no ignoring the systemic inadequacies that already exist and will only continue to grow and spread.

It’s true, as Frey mentions in his report, that child poverty rates were on the decline in the decade leading up to 2019, but the racial disparities in the rates across the nation, which were even more profound in Houston, are undeniably significant. And that was before the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated most of the already existing divides.

When the 2020 Kinder Houston Area Survey came out almost a year ago, it showed almost 40% of Harris County residents were unable to cover an emergency expense of $400. Over 30% of Harris County households have incomes of less than $37,500 a year. Paying for groceries to feed their family was a problem for 35% of residents, while 35% struggled to pay for housing. And nearly one-quarter of families have no health insurance.

Houston is among the major cities that have the highest percentage of children without health insurance. In Texas, 13% of the those 18 and younger are uninsured; in Houston, it’s 16%. Among all Texans in 2019, 18.4% were without health insurance, the most in the nation. More than two-thirds (69%) of Texans support Medicaid expansion, according to recent polling from the University of Houston Hobby School of Public Affairs. Despite that, on Thursday, the Texas House voted down an attempt to expand health care coverage for uninsured Texans using federal funds.

When the economically vulnerable residents who responded to the 2020 Kinder Survey are broken down by ethnicity, sizable racial disparities can be seen:

► 36% of U.S.-born Hispanic households make less than $37,500 a year

► 42% of African American households earn that much annually

► And more than half of Hispanic immigrant households make less than that in a year.

In contrast, 83% of white households made more than $37,500, as did 82% of Asian households.

When asked how they would cover the cost of a $400 emergency expense, more than 60% of Hispanic immigrant households said they couldn’t. Close to half of U.S.-born Hispanic households and 56% of African American families wouldn’t be able to afford the expense. That’s compared to 16% and 30% of white and Asian households, respectively, that wouldn’t have the money in an emergency.

And it’s important to note the 2020 report was based on survey results gathered before the pandemic. One of the best ways to eliminate persistent economic inequalities is through improved access to education.

“Indeed, you could make the argument that achieving substantial improvements in early education will be as important in building the conditions for this city’s and nation’s prosperity in the twenty-first century as was the dredging of the Houston Ship Channel (1910–1920) or the completion of the Interstate Highway System (1956–1991) in contributing to the thriving economy of the twentieth century,” Klineberg writes in “Prophetic City.” “But it’s a long game that too few seem willing to play.”

However, in 2018, the Kinder Houston Area Survey showed Houston-area residents overwhelming support (67%) increasing local taxes to provide universal preschool education for children. Four in 10 indicated they were strongly in favor of such a proposal. “This is a remarkable degree of consensus for a population that is so well-known for its opposition to increasing taxes for almost any purpose,” according to Klineberg.

Klineberg and Frey both argue that greater investments in children today — including increased attention and improvements to education, raising pay for teachers, support for child care, caregiving and more social support for less-affluent children and their families — are the only way to ensure the success of the country.

But will it happen?

President Joe Biden has unveiled a $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan that would provide what he calls a “once-in-a-generation investment” in the nation to pay for a number of key provisions, including building schools, affordable housing, hospitals and child care facilities, roads and bridges, public transit and high-speed broadband. Biden has also announced the American Families Plan, which will fund “human infrastructure” like education and child care. In response to the Biden infrastructure plan, Senate Republicans this week released a significantly smaller $568 billion counterproposal.

“The critical questions for Houston’s future rest with the fates of these Hispanic immigrants and their children, for they will constitute the largest part of the city’s future workforce,” Klineberg writes. “Will they continue to be locked in poverty, fueling the growth of a new underclass, as educational disadvantages effectively prevent them from moving forward? Or will they be able eventually to work their way into the middle class, gradually improving their circumstances and expanding the chance for better jobs for themselves and their children?”