Houston was born from bold entrepreneurialism and big infrastructure.

The Allen Brothers put the city on the map as a hub of the transcontinental rail network. The Ship Channel connected Houston to the world, enabling it to become the capital of the oil and gas industry.

NASA made Houston famous around the world as Space City.

In the past 30 years, Houston has become one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse major metropolitan areas in the U.S. The city’s diversity may be its most valuable asset in its efforts to reinvent itself. But, as the most recent Kinder Houston Area Survey has shown, Houston is plagued by ethnic inequalities, including those related to health care, economics and education. If unaddressed, these inequalities are sure to limit the region’s economic growth in the coming years.

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

Houston is currently getting hit with a powerful double threat: the COVID-19 crisis and the energy downturn. The shocks of these catastrophes are coming on top of the devastation of Hurricane Harvey less than three years ago; they also highlight several of the long-term stresses and vulnerabilities that disproportionately affect disadvantaged communities in the form of flood impacts in low-lying areas, air quality problems adjacent to freeways or industry, and lack of connectivity in neighborhoods underserved by transit.

All of these events are hurting Houston right now, but they provide the city and its leaders with long-range opportunities for reinvention.

It is time to imagine a Houston that is a bigger and better version of itself.

Houston needs to reinvent itself

All great cities must reinvent themselves on a regular basis. Boston, for example, has remade itself a number of times over the past 400 years. It’s been a port town, a manufacturing center, a tech hub and the world’s leading center of higher education.

Houston has reinvented itself at least once. In the early 20th century, the city used its commercial and transportation strength — along with sheer American entrepreneurialism and engineering ingenuity to pivot from cotton and timber to oil. As a result, Houston became the most iconic global city of the last century’s carbon economy era.

Now it’s time to do it again. Coming out of the pandemic and the energy downturn, what are the big moves Houston can make to reinvent itself for the 21st century?

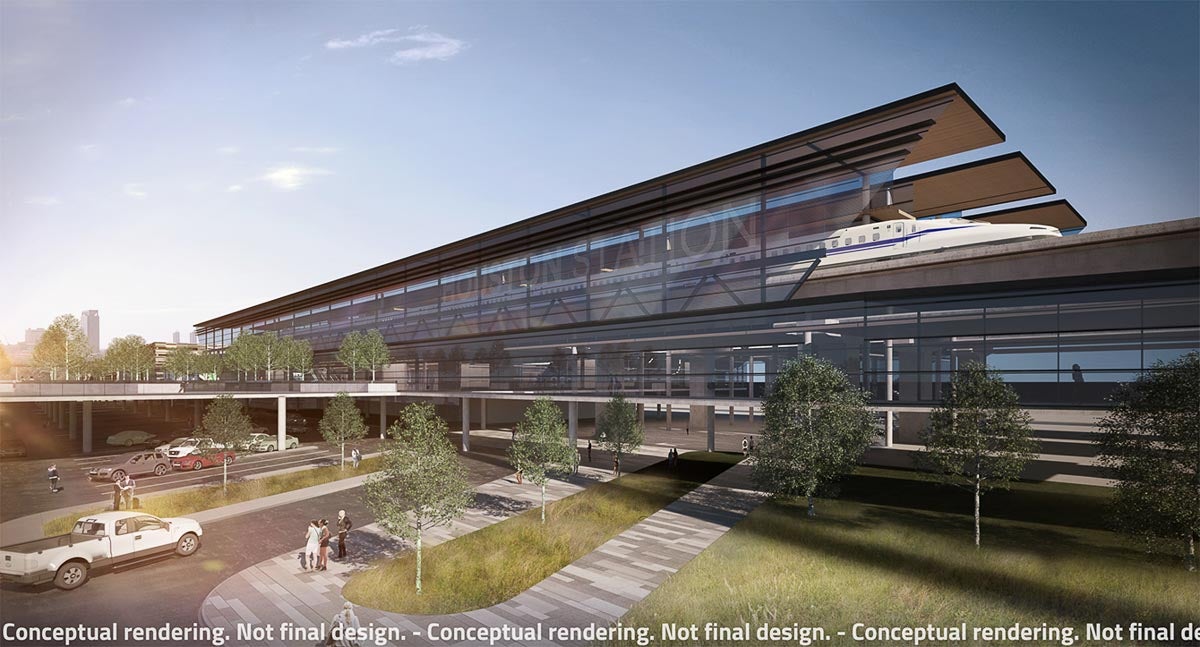

Source: Texas Central

Energy and infrastructure are key

Obviously, many steps must be taken. For example, Houston must determine the best way to restore the vibrant city life that existed before COVID-19 while addressing the endemic inequities that existed. And in the long run, the city has to figure out how to work the energy transition to its advantage. That means finding a way to remain the world’s energy capital even as alternative energy sources become more common. Texas already is the nation’s leader in wind energy, and its largest energy companies must continue to evolve beyond being the world’s largest oil and gas companies and become the world’s largest energy solutions companies.

And the city must reinvent its physical form to reflect the current century, not the last.

There is no more powerful way to rework the city’s physical form than transforming the infrastructure required to power its growth — especially when that infrastructure can provide a city with multiple benefits. Don’t forget that San Antonio’s transformative River Walk — the city’s leading tourist attraction after the Alamo — is actually a Depression-era flood control project devised by a local architect after a catastrophic flood in 1921.

As it happens, Houston is on the cusp of several large infrastructure projects that have the potential to transform the city, including:

► The proposed $7 billion expansion and realignment of I-45 through central Houston.

► A new round of flood control projects funded by the $2.5 billion 2018 flood control bond, including the North Canal and a series of property buyouts.

► Major storm surge control efforts in Galveston Bay, including major levee and floodwall improvements to protect the Ship Channel ($20-30 billion), and an innovative approach to creating a new regional park with additional flood protection in the middle of the Galveston Bay ($3 billion).

► Houston Metro’s $7 billion MetroNext improvement program for Houston’s transit system.

► The $20 billion Texas Central high-speed rail project, which will connect Houston to Dallas in 90 minutes and terminate at the former Northwest Mall site.

► The $220 million Bayou Greenways 2020 linear park project and the subsequent “Beyond the Bayous” plan to connect bayou greenways to other green spaces and destinations in the Houston area.

When considered against an annual GDP of $490 billion for the Houston Metropolitan Area, they all seem like wise investments. Any one of these pieces of infrastructure would be transformational to any metropolitan area in the country. Together, they have the potential to completely reinvent Houston for the 21st century, but only if they respect existing communities and are designed to deliver economic, environmental and equitable co-benefits.

The I-45 expansion, for example, holds the potential to transform the city’s Downtown and Midtown areas, but it must also serve the interests of those who live north of Downtown. As Mayor Sylvester Turner said recently, “If I-45 can be designed and constructed in such a fashion that the freeway disappears and you have more green space, more park space, then that's a tremendous plus in the way that it mitigates the risk of flooding and reduces greenhouse gases. From an environmental point of view, those are big pluses.”

Source: Rogers Partners

Changing the way infrastructure projects are viewed

But how does Houston break out of the typical infrastructure silos and deliver all of these projects to create a more resilient and equitable 21st-century city?

Conceptually, perhaps the most important change is simply to view these projects through a different lens.

► The North Canal in Downtown isn’t just a flood control project. Potentially, it’s a way to improve Buffalo Bayou Park and Downtown’s increasingly amenity-rich urban footprint.

► As designed, the I-45 highway project helps reconnect long-separated neighborhoods in Downtown and Midtown. But, by integrating equity, it can revitalize historically African American neighborhoods north of Downtown and protect them from flooding.

► The Texas Central should be viewed not as a high-speed rail line with a terminal in Houston, but a catalyst for connecting Downtown, Uptown and the 610/290 area by transit.

► The flood protection programs for the Galveston Bay will protect one of the most important pillars of the global economy, the Houston Ship Channel and its energy sectors, but it can also create a magnificent new way to enjoy the bay itself.

Source: Texas Central

Getting creative in funding infrastructure

Finding innovative ways to finance these projects is equally important. In the wake of COVID-19, public funding for infrastructure projects likely will be scarcer at first. Houston leaders should lobby Austin and Washington DC for post-pandemic stimulus funds that encourage new infrastructure delivery. But, it also will be necessary to find creative ways to finance new infrastructure — not just to pay for it, but to reinforce the idea that infrastructure can have multiple benefits.

For example, the Milken Institute, in collaboration with AECOM, convened a Financial Innovations Lab® to look at the coastal resilience program proposed for Lower Manhattan. The lab participants examined a variety of funding and financing options that could be applied at different scales. Various options for raising money through a bond program could be applied at a city level. At the regional or state level, more funds could be collected through a 2% surcharge on insurance policies, which could be saved in a trust fund managed by an independent entity. In addition, the city could include revenue-raising models in its plans, from selling private development rights to utility charges to surcharges that are income-dependent.

The goal was to map out the right mix of capital sources and investment types to bridge funding gaps. This type of fiscal investigation of how to fund infrastructure would be a key condition for success for Houston as it embarks on this new generation of infrastructure investment.

This may be the right time to do the impossible

There is no question that COVID-19 will change how we live in cities around the world. But, as Mayor Rahm Emmanuel says: “Never allow a good crisis to go to waste. It’s an opportunity to do the things you once thought were impossible.” This is especially true in Houston — which has been bombarded by so many crises in the past few years — the very existence of the city depends on reinventing the way we approach big infrastructure projects.

We need to reorient the city around not just traffic and flood control, but public health, climate change and social challenges to ensure that Houston will be a cutting-edge 21st-century city.

Stephen Engblom is an urban design/architect based in San Francisco. He is an alumnus of Rice University School of Architecture, where he sits on the William Ward Watkin Advisory Council. He is an Executive Vice President and Global Cities Director with AECOM.

William Fulton is an urban planner who serves as the Director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University. He is a former Mayor of Ventura, California, and Director of Planning and Economic Development for the City of San Diego.