Preventive health care as a concept isn’t anything new or exciting, but there are parallels that can drawn from it to both the current pandemic and climate change crises. Early in the time of COVID-19, the U.S. was caught flat-footed in its response — unprepared to successfully track the spread of the disease and unable to adequately protect many frontline health care workers because of personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages. Who wants to spend money to manufacture and stock up on respirators and surgical masks that may never be used? That seemed to be the general attitude toward pandemic preparation before COVID.

Unfortunately, as humans, we have trouble seeing prevention as treatment. It’s hard to prove you didn’t have a heart attack or get cancer, but preventive health care works. Though it may seem expensive or even unnecessary now, in the long run, prevention will be worth it and much less costly.

It’s not much different from the approach policymakers, business leaders, the average American and more than one president have taken to climate change and global warming over the past 50-plus years. Convenience, profits and a higher standard of living are a few reasons we’ve willingly buried our heads in the sand and ignored the science and the warnings. And now, perhaps, prevention is no longer an option. The cancer was detected a long time ago but we’ve largely ignored the diagnosis. Now that it’s progressed to an advanced stage, it’s unclear if any treatment will be effective. Despite that, we must err on the side of optimism and make some healthy lifestyle changes as a species.

Hyperproximity and the benefits of the 15-minute city

It just so happens that convenience, profits and a higher standard of living are among the benefits of the “15-minute city,” a climate-action initiative that promotes neighborhood-level planning. The concept has been around for years but has been a trending topic since its reintroduction in 2019 by French academic Carlos Moreno, an adviser to Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo. Inspired by urbanist-activist Jane Jacobs, Moreno’s vision for the 15-minute city is one of “hyperproximity,” where residents are within a 15- or 20-minute walk, bike ride or transit ride of daily needs such as grocery stores, restaurants or cafes, schools, workspaces, health care facilities, parks and green spaces, and essential services.

The goal is reducing the need to use a car for most errands by increasing urban walkability, which will cut greenhouse emissions; but just as importantly, it’s a holistic approach to improving livability and quality of life in cities, and do it in an equitable way.

“Preserving our quality of life requires us to build other relationships between these two essential components of urban life: time and space,” Moreno said in a statement.

“This means giving back the city its most valuable attribute, i.e., being a living universe, to restore its metabolism, like any living organism, to make the city alive and available to all.”

Moreno also advocates for rethinking and reinventing public spaces to maximize their benefits for the most people. One example is the conversion of street parking into pedestrian plazas, green space and bike lanes in Paris. Another is using school playgrounds as neighborhood parks during off-hours, a hybrid approach akin to the SPARK School Park Program in Harris County.

People want walkable urbanism — even in the suburbs

In each of the past 12 years, the Kinder Houston Area Survey has shown that 50% of Houstonians want walkable urbanism and streets “reconfigured to accommodate not only motorized vehicles, but also bikers and pedestrians,” Stephen Klineberg, the Kinder Institute’s founding director, wrote in the 2020 survey report. “Real-estate developers are slowly responding to the new demands by building more transit-oriented, walkable communities, not only in Houston’s downtown areas, but also in the urbanizing town squares and centers that are sprinkled throughout this far-flung multi-centered metropolitan region.”

And walkability isn’t an aspiration exclusive to residents of the urban core, the report contends. A 2019 report called “Foot Traffic Ahead” examined the level of walkable urbanism in the 30 largest U.S. metros based on the share of total retail, office, and multifamily housing space located in each metro's "walkable urban places” — referred to as WalkUPs. According to the report, a significant portion of the growth in WalkUPs has been in the suburbs, as much as 44% in Miami and Washington, DC, and 40% in Boston. Just 5% of the walkable urban development in the Houston area occurred in the suburbs as of 2018. Examples include City Centre, Pearland Town Center, Sugar Land Town Square and Market Street in The Woodlands.

The report showed Houston’s 89% rent premium was the third highest in the country, meaning tenants were willing to pay almost twice as much for office, retail and multifamily rentals in walkable urban areas compared to the suburbs.

Through its Walkable Places program and ordinances to promote transit-oriented development, city leaders and planners are steering Houston toward building places that make cars less of a necessity if not optional.

The city ordinances will roll back some land-use regulations, such as requirements for minimum setback and the number of off-street parking spaces. It also establishes urban planning rules like minimum street-width requirements, pedestrian realm standards such as minimum sidewalk size, shared driveway access for single-family homes on subdivided parcels and bicycle parking standards.

Do you live in a 15-minute neighborhood?

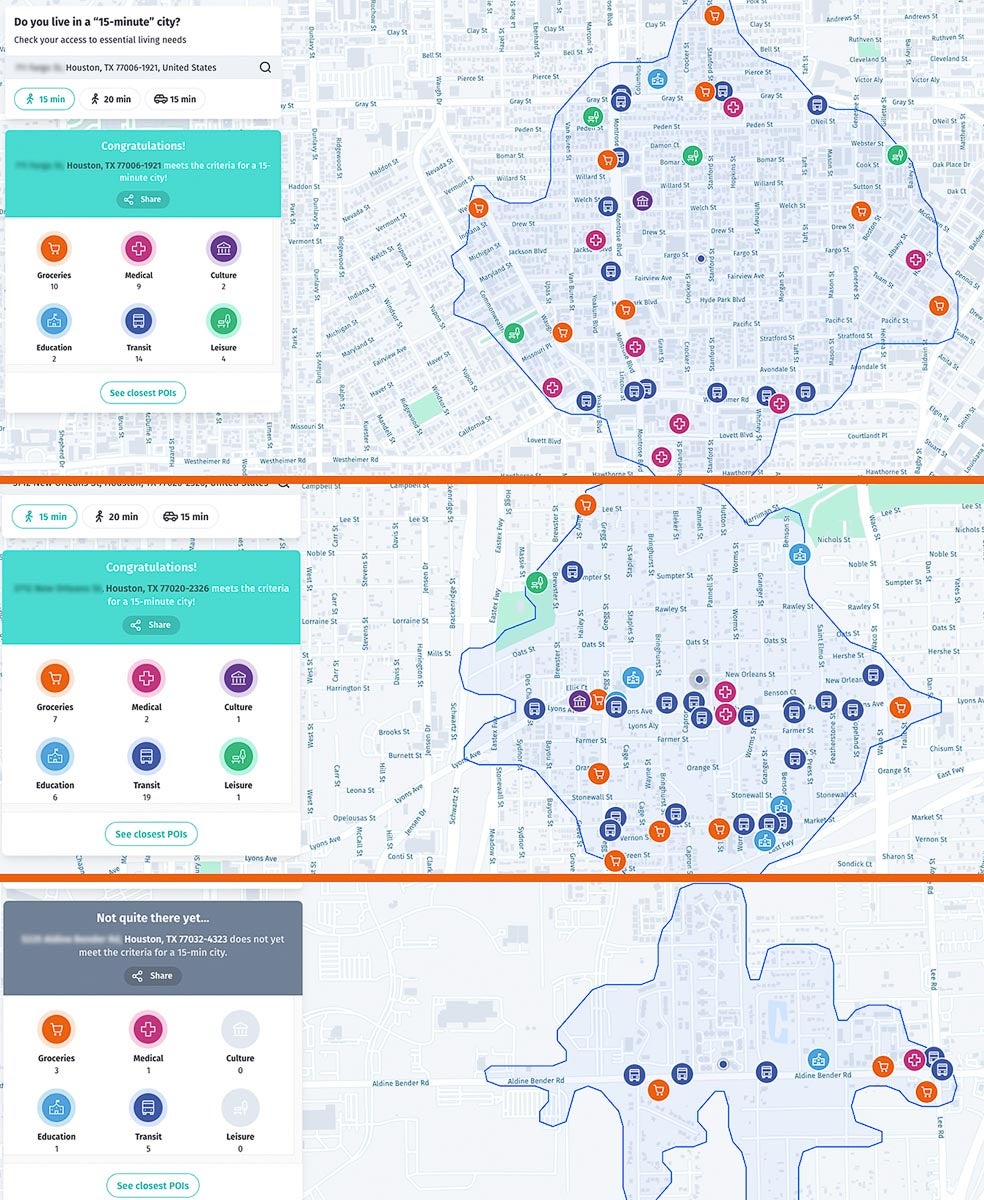

It’s easy to see why cynics may poo-poo the idea of Houston being a 15-minute city, but the coronavirus pandemic’s acceleration of remote work has made pulling off the concept a possibility in some neighborhoods. You can see if you live in a 15-minute neighborhood with an app developed by digital mapping company Here Technologies. Just plug in an address and the app will map medical care facilities, grocery stores, arts and cultural attractions, transit stops, schools, restaurants and more within a 15- or 20-minute walk.

According the app, my address meets the criteria for a 15-minute city; however, a pocket park the app shows to be near my house was placed in the wrong location — it’s actually farther than a 15-minute walk. The app also has a few glitches in its ability to accurately categorize some businesses. For example, the now-closed Atlantic Coffee Solutions coffee plant on Harrisburg Boulevard is identified as a grocery store by the app. It’s not perfect, but the Here app does a good job of providing a sense of what is — and isn’t — available close to home.

What else can cities do to make neighborhoods more livable and walkable? To help, Strong Towns offers its “7 Rules for Creating 15-Minute Neighborhoods.” As Minneapolis planner Paul Mogush phrased it, many of the suggestions “put the stuff closer together so it’s easier to get to the stuff.”

1. Bring back the neighborhood school.

2. Make sure food and basic necessities are available locally. (Improve access to food)

3. Third Places come in all shapes and sizes. (A third place is a community gathering space such as a pocket park, plaza or public library.)

4. House enough people, and all kinds of people.

5. Density isn’t enough (and it’s more than high-rises).

6. Sweat the small stuff for true walkability.

7. Know when to get out of the way. (Ease regulations that are obstacles to better urban design.)

The goal of Moreno’s amour des lieux, or attachment to place, “is not to wage a war against cars,” he told Here Technologies’ Here360 blog, or “build a Louvre every 15 minutes” but as a way to help shift priorities. Moreno explained:

“In Paris, 66% of the public space is streets for cars. But individual cars move only 17% of the population. And each one of the cars, we found, have only two people in each car. This is totally opposite to the concept of hyperproximity.”

Houston, of course, is not Paris. It’s a unique place with its own opportunities and challenges that are very different from most cities beyond the Sun Belt.

In a conversation local writer Allyn West had with David Fields, Houston’s first chief transportation planner, over the summer, Fields talked about transportation demand management. “That is an approach of policies and programs that encourage people to use the entire transportation system to balance the playing field,” Fields explained. “If you want to drive and need to drive, that’s a choice you can make, and we can accommodate that.

“But we have a lot of different systems. Certain communities or businesses have provided free transit passes, for example. But there are many different components with transportation demand management that you can make specific to a community that can allow and encourage people to choose the different systems.”

Through its Complete Streets and Walkable Places programs, Climate Action Plan and other planning initiatives, the city has made a commitment to prioritizing pedestrian and bicyclist safety in infrastructure investments. Though it remains to be seen how it will put all of these plans into practice when drivable suburban development remains the dominant public policy. On paper, the ideas look great, and progress has been made, but it’s an ongoing, evolving process.

Going back to Moreno’s metabolism metaphor, a city, like any living organism, is constantly growing, changing and, with the right planning, improving for all of its residents.

Do you live in a “15-minute” city?

Three randomly generated Houston addresses were plugged into the Here Technologies app to see if they meet the criteria of a 15-minute city:

(Top) ZIP code 77006: This Montrose address meets the criteria and is within a 15-minute walk of 10 grocery stores, nine health care facilities, two cultural amenities, two educational facilities, 14 transit stops and four parks or green spaces.

(Middle) ZIP code 77020: This Fifth Ward address meets the criteria and is within a 15-minute walk of seven grocery stores, two health care facilities, one cultural amenity, six educational facilities, 19 transit stops and one park or green space.

(Bottom) ZIP code 77032: This address on Aldine Bender, south of George Bush Intercontinental Airport, does not meet the criteria of a 15-minute city. It’s within a 15-minute walk of three grocery stores, one health care facility, zero cultural amenities, one educational facility, five transit stops and zero parks or green space.