A city like Houston – sprawling, less dense, and largely suburban - can feel urban when it provides an urban lifestyle, primarily through what is often termed “walkability.” While difficult to put into a single definition, walkability generally means safe and pleasant pedestrian access to a range of uses and amenities either by foot or transit. Walkability is an increasingly sought-after characteristic as people choose where to live and work, regardless of density. Manhattan and San Francisco are walkable, but so is a thriving small town Main Street, activated by lively street fronts and safe sidewalks, easily accessible from residential neighborhoods. Reacting to this desire for an urban lifestyle, the City of Houston is working to further incentivize walkability within the city code. At the same time, private developers are integrating walkability into the built landscape with the few tools already at their disposal.

Without official use zoning, two major elements in the City’s code have shaped the urban environment of Houston since the 1980s – setback requirements based on City designated street type and use (Chapter 42) and parking requirements based on use (Chapter 26). Generally, these requirements have created what many would argue is a suburban landscape with large building setbacks and an excess of parking, ideal for strip mall and big box development, but not the urban place making of a vibrant city.

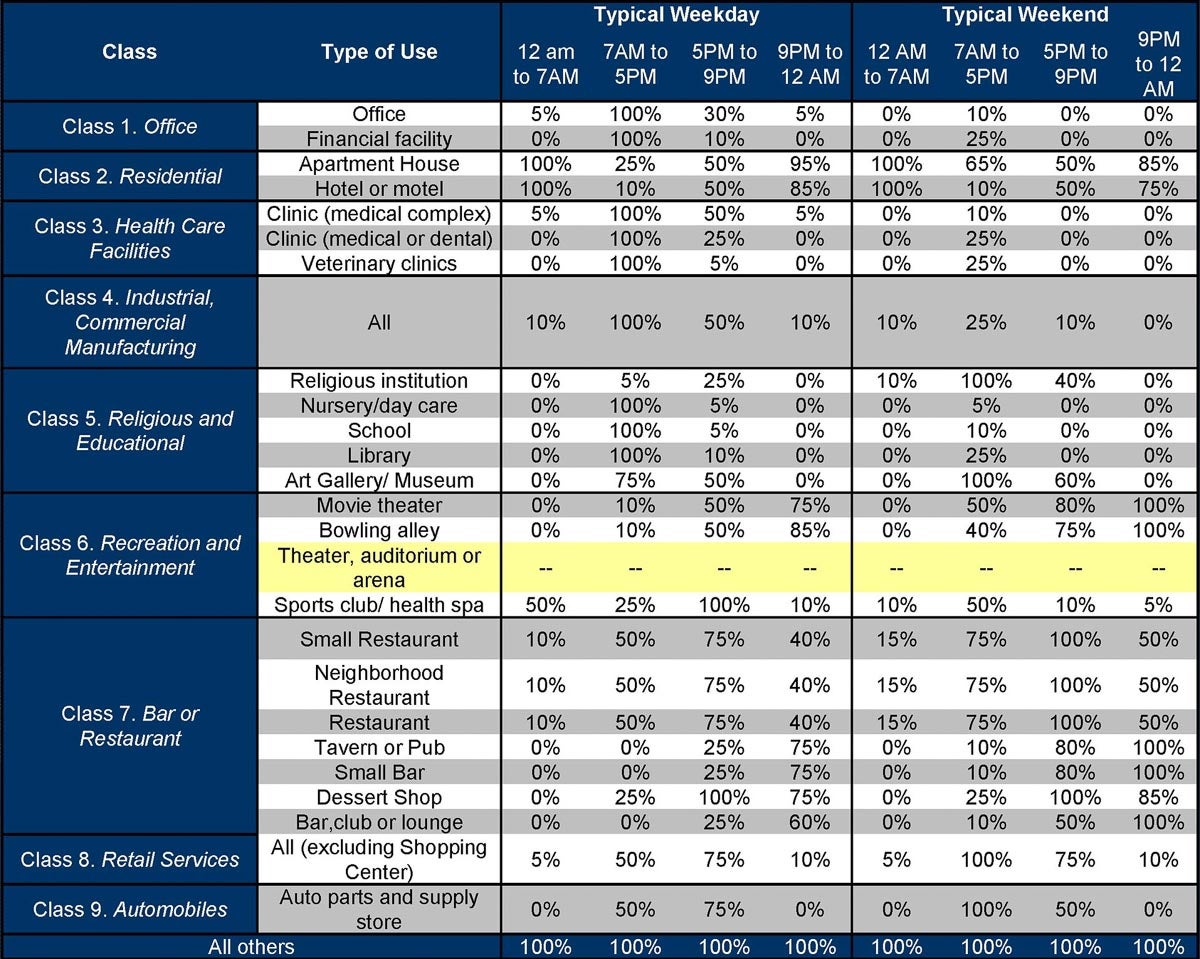

The code does include several small incentives for developers to create more walkable spaces. For example, if developers provide more bicycle parking than is required, they can then build up to 10 percent fewer parking spaces. And the shared parking ordinance allows parking spaces to be shared by different uses at different times of day, in theory encouraging mixed-used development, a hallmark of walkable neighborhoods. Developers that re-use a historic building, thus maintaining the character of a historic neighborhood, can also qualify for a 40 percent reduction in parking requirements.

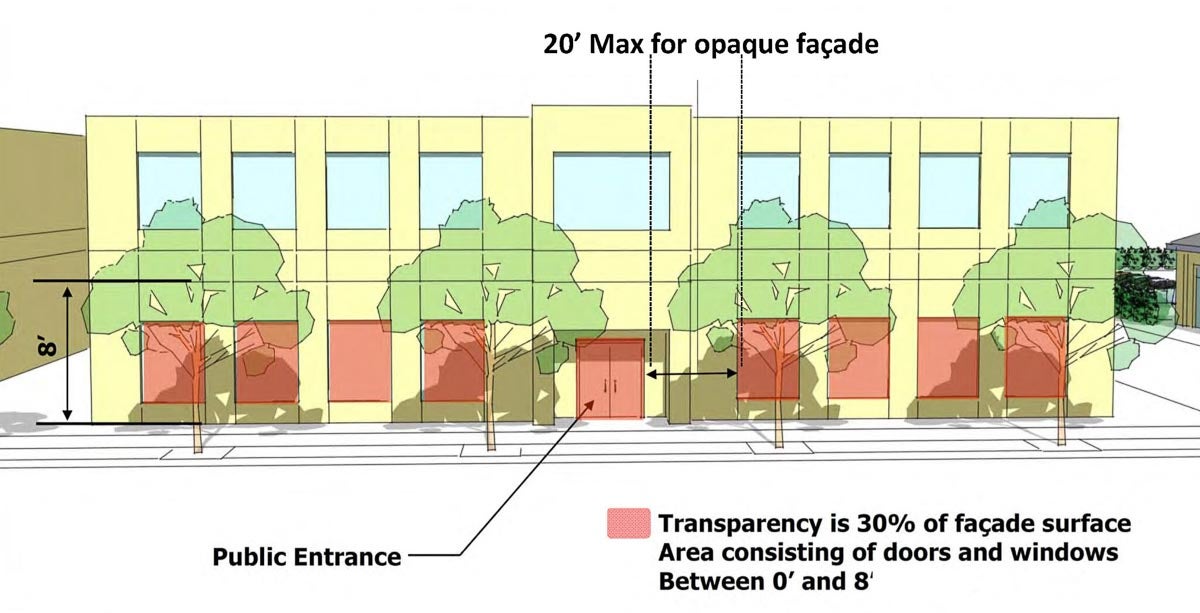

In 2009, the City took another step toward walkability, adopting the Transit Corridor Ordinance to stimulate more built density, and hopefully, walkability along public transit corridors. Under the ordinance, if property owners follow certain pedestrian-friendly building guidelines, they can build up to the lot line and are given a 20 percent reduction in the amount of parking required.

But all of these incentives are voluntary and debatably effective. According to Muxian Fang with the City's planning department since 2009 only 17 percent of projects eligible for the Transit Corridor incentives chose to opt into them.

Now the City is hoping its latest effort will provide more effective tools for incentivizing and prioritizing walkability. The recently established Walkable Places Committee has been tasked with reevaluating the city code to dive deeper into the issue of walkability in Houston. The committee is currently focused on creating an application-based process to establish specific “walkable place” areas. Under this new system, any neighborhood could voluntarily apply to become a “walkable place” and in doing so establish their own set of self-defined unique rules for development to encourage walkability. These rules would include specific regulations covering the building setback, design of the pedestrian realm, landscaping, pedestrian friendly building design, and parking (a separate subcommittee has been formed exclusively to deal with parking).

But once adopted, unlike the Transit Corridor Ordinance, neighborhood- and site-specific building rules would be required, not optional, for all new development. Though still in the early planning stages – adoption of a new ordinance is targeted for 2019 – the proposal certainly faces challenges. How will a neighborhood come to consensus on new guidelines? What are the incentives to apply to become a “walkable place?” What will trigger the application of the new guidelines to existing development? Are historic structures exempt? And perhaps most importantly, what about the spaces between and connecting to the specific neighborhoods?

Details aside, this approach embraces one of the core concepts promoted by Jeff Speck, leading writer on walkability and the author of “Walkable City,” that each city must “pick your winners.” Not every street or neighborhood is going to be walkable and the city must make a conscious choice about where to allocate energy and resources. The application based process would encourage neighborhoods with a high potential for walkability to work together to maximize that ability.

The plan, though, entirely neglects the issue of access and connectivity to and between the new walkable neighborhoods, which is why many on the committee also support modifying the code city-wide. Could parking requirements be minimized, or even eliminated, allowing the market to dictate how much parking to provide? Could minimum building setback requirements be decreased overall? Though such sweeping changes seem unlikely at this point, hopefully these designated walkable places could be testing ground for new requirements, which could be adopted city-wide in the future.

In lieu of such changes, several developers have taken advantage of the existing incentives in notable projects around town. But, despite incorporating laudable design elements, these projects also reveal the limitations inherent in the city’s current scheme.

Radom Capital’s Heights Mercantile, designed by Michael Hsu Office of Architecture, is a complex of renovated existing and new buildings in the Heights housing restaurants, retail, and office lofts. Located off Yale Street, though not a Transit Corridor, it is designated a Major Thoroughfare which allows a 5-foot building set back for retail centers if certain requirements are met, including maximizing the building frontage along the street and moving parking to the back. Additionally, two of the buildings are within the Heights South Historic District and therefore qualify for the 40 percent reduction in parking requirements. Located at the intersection of the Heights Boulevard linear park and the Heights Hike and Bike Trail, the project is inherently accessible and walkable within the already largely walkable neighborhood of the Heights. This project has the built in advantage of a pre-existing walkable context which likely helped inspire the development itself.

Heights Mercantile Plan.

Alternatively, another prominent new project along Richmond Avenue highlights the tensions within Houston’s current regulations when applied to a less walkable context. Kirby Grove, an 11-acre mixed-use development from Midway, the developer behind CityCentre, offers retail, office, and residential units oriented around the redeveloped Levy Park. The development took advantage of the Transit Corridor incentives available along Richmond Avenue to maximize the building footprint and reduce the parking load. But it’s stubbornly inaccessible. Despite the beautiful design and thoughtful programming, the development remains a disconnected; walkable within but hardly to or from. Because the Transit Corridor incentives are optional, Richmond Avenue, without any sign of the upcoming Light Rail line which earned it the Transit Corridor status, remains largely unwalkable along this stretch, with buildings set far back from an already sprawling six lanes of traffic and parking obscuring most building frontages. While future projects along this stretch may eventually also opt in, the existing fabric faces no pressure to change.

Kirby Grove site plan.

Levy Park.

Richmond Avenue.

To eschew the City’s control, other developers have focused on areas with fewer restrictions like Midtown and East Downtown. As part of the Central Business District of Houston, these developments are exempt from parking requirements and building line requirements in the code. In East Downtown, Ancorian has been developing the East Village complex, an adaptive reuse project set to add 100,000 square feet of retail and office. Crosspoint Properties has been developing blocks of Midtown into walkable, mixed-use developments since the early 2000s, most recently with its Mix @ Midtown district. Many would argue that developers should focus on walkability and density in these areas which already have a tight urban grid and little opposition from local residential neighborhoods.

East Village rendering.

māk studio

Mix @ Midtown.

With thorough research and careful planning, the existing regulations and incentives do offer the opportunity for walkable, creative, and urban-feeling development in Houston. But with strict regulations and only optional incentives, developers are not always motivated to put in the extra effort. Even so, individual developments can only do so much, as connections and context are paramount in placemaking and walkability.

To ensure – rather than just hope for – walkable developments, the City does need some sort of non-optional building requirements along the lines of what the Walkable Places Committee is planning. But to create walkable neighborhoods and a more connected city overall, the city needs to revisit the city-wide code, reconsidering everything from set back distances to parking requirements.

Hilary Ybarra is an architect and principal at The Platform Investment Group, LLC, focusing on leveraging the power of design in real estate development in the Houston area.