As the nation’s fourth most populous city, Houston is clearly an urban center, and yet, the lifestyle it provides is largely suburban. Many people live what could be mistaken for a typical suburban life - residing in single-family detached homes, driving cars to work, shopping at big box stores and dining in strip centers. In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, Houston’s supposed unchecked suburban sprawl has come into focus and under attack. How urban, or suburban, is Houston really? How do we even define what is urban and suburban?

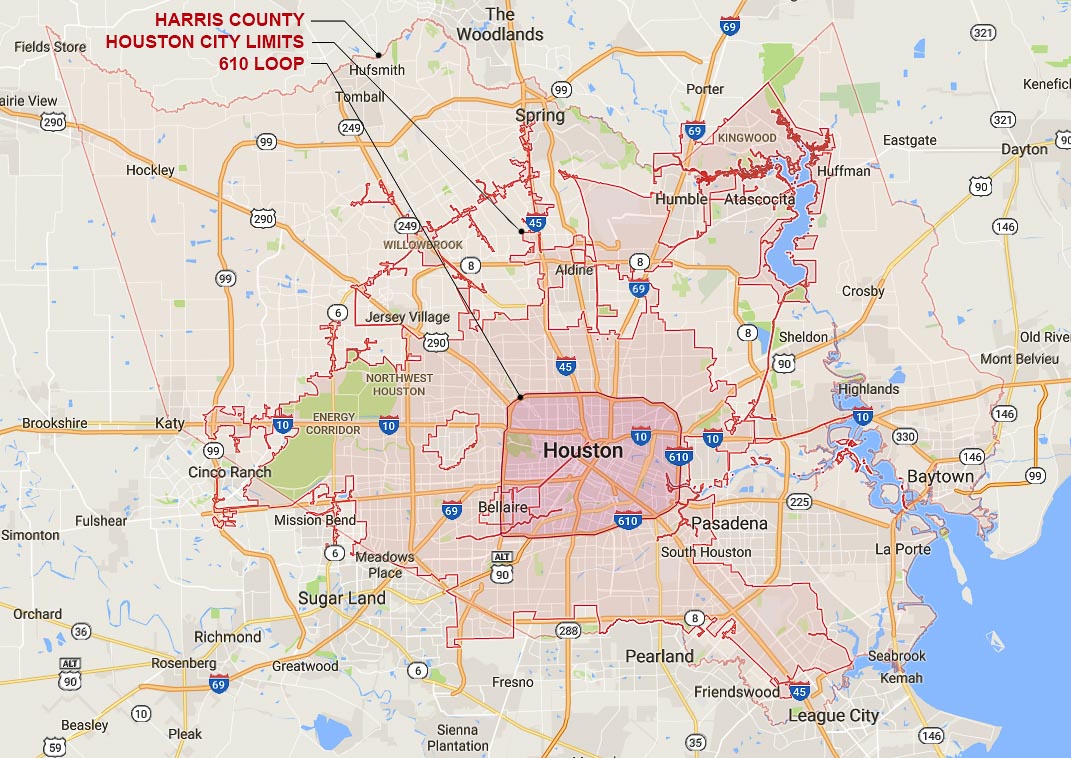

In theory, the city itself is “urban” and the area just outside the city is “suburban,” but Houston’s geography, by no means, offers a clear distinction between where the city ends and the suburb begins. Officially, Houston city limits reach out to NASA, George Bush Intercontinental Airport and the Energy Corridor – 667 square miles, the largest land area by far of the 10 most populous cities in the country. Included within the city limits are peripheral suburbs like Kingwood, Willowbrook and Edgebrook, and excluded are a few interior residential neighborhoods like West University, Bellaire and the Villages, already confusing the boundary between where the city stops and the suburbs begin. The 610 loop encompasses Houston’s downtown and immediate surrounding neighborhoods and for many residents it defines the urban core of Houston.

Yet even within the 610 loop, Houstonians are well aware of the differences between suburban feeling residential neighborhoods like River Oaks and Spring Branch and the more urban job centers like downtown and the Medical Center. Even the sacred boundary of 610 is beginning to blur; in 2013, the City of Houston Municipal Code expanded development regulations which previously applied to major thoroughfares only within the “urban” area of the 610 loop to all of Houston’s city limits, no longer deeming the area outside of the loop - yet within city limits - as “suburban.” There remains no clear physical boundary between Houston and its suburbs, rather pockets of different experiences spread out within and beyond the city limits.

Density is often the default qualifier of what makes a place feel urban, yet the threshold between urban and suburban density can be hard to pin down. Economist Jed Kolko conducted a survey of Trulia users to determine that a population density of over 2,213 households per square mile generally feels “urban;” between 102 and 2,213 is perceived as “suburban.” By Kolko’s analysis of the 2010 Census, Houston is 63 percent urban and 37 percent suburban.

Of the 10 fastest growing cities in the country, while not nearly as urban as cities like New York, Chicago or Los Angeles -- 100 percent, 100 percent, and 87 percent urban respectively -- Houston is more urban than many of the other rapidly growing urban centers of the south and west like Dallas, San Diego, San Antonio and Phoenix -- 60 percent, 49 percent, 35 percent, and 30 percent respectively. By Kolko’s account, Houston’s population density may not be as urban as the other largest cities in America, but it is not nearly as suburban as many other cities.

Houston tends to feel suburban largely because of its typically suburban building stock – single-family homes and strip malls. A study by the Kinder Institute indicates that 61 percent of Harris County’s housing is single-family detached homes. The same study suggests that more urban typologies like townhouses and multi-family buildings are being built faster than single-family detached homes, indicating that the residential fabric is in fact urbanizing.

Still, without access to a range of commercial activities and amenities, either by walking or public transit, even the most urban typologies can fail to provide an urban lifestyle. As one might expect, Houston’s densest two neighborhoods – Gulfton and Westwood – are made up of high-rise apartment buildings, a typical urban typology. Yet these complexes developed in the 1960s and 1970s are built as superblocks at highway interchanges, completely isolated from other uses. These neighborhoods ultimately fail to provide their residents, largely Hispanic, foreign-born and living below the poverty line, any sort of urban experience. At the same time, Montrose is composed of a mix of residential building types of varying ages and is one of Houston’s most walkable, commercially vibrant and densest neighborhoods, with very few of its residents living below the poverty line. Clearly, residential typology alone does not indicate an urban or suburban experience.

The City of Houston and its residents seem aware of the importance of walkability and transit access in creating a more urban experience, an amenity which is increasingly sought after. Houston has a walkability score of 49, the highest city rating in Texas, though a far cry from cities like New York and San Francisco. Many neighborhoods, though, far exceed this rating – Midtown (86), Montrose (82), Museum District (79), and Downtown (76). A new Walkable Places Committee has been formed under the City Planning Commission to specifically tackle walkability, taking a closer look at the rules and regulations that guide development in the city. Houston receives an AllTransit Performance score of just 6.24 out of 10 and only 4.34 percent of commuters utilizing transit. Again, while not close to the scores of New York and Chicago, 9.6 and 9.1 respectively, Houston is on par with or ranking higher than other Sun Belt cities, like Dallas at 6.82, San Diego at 6.1, Phoenix at 5.8 and San Antonio at 5.7. The new light rail and revamped bus system indicates that Houston is working towards a more transit-connected city, even if it is slow going and debatably effective.

Houston’s lack of traditional zoning or aesthetic guidelines has in many cases created a range of uses and design that inspire vibrant urban life, though not always in the traditional sense that urbanists or visitors might expect. While still rare to find buildings with ground floor retail and office or residential above, the ubiquitous typology of cities like New York and Chicago, Houston can boast streets like Westheimer with different uses and designs side by side - an artisanal bakery next to a tattoo parlor next to a historic bungalow next to an office high rise. As Nolan Gray, host of the Market Urbanism podcast, writes, this unique situation actually offers, “A stressful experience, perhaps, for the orthodox planner who prefers conformity and order, but an exhilarating experience for residents who appreciate the spontaneity and novelty offered by urban life.”

For Houston, it seems geography, density, building typology and lifestyle may not always align in expected patterns to create an ideal urban experience, yet amidst the sprawling highways and residential subdivisions, there are certainly promising trends toward a more urban, but still uniquely Houstonian, lifestyle and many moments of vibrant urban experience already out there, so long as one knows where, and how, to look for them.

Hilary Ybarra is an architect and principal at The Platform Investment Group, LLC, focusing on leveraging the power of design in real estate development in the Houston area.