“If cities want to provide affordable mobility, if we are going to make progress on climate change and reducing emissions, public transit is a huge part of that. And improving bus service is integral to improving public transit.”

— Steven Higashide, urban planner and public transportation expert

We’re close to wrapping up a phone call earlier this week when Steven Higashide brings up zombies.

He’s discussing “Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit,” his book about the powerful impact fast and reliable public transit — specifically, buses — can have on cities. The zombies he’s talking about are the zombie policies related to urban highway expansion.

It’s the first of two times in as many days that I’d have zombies on the brain.

The second — less than 24 hours later — was an interview New York Times columnist Paul Krugman did with “Marketplace Morning Report” to promote his new book, “Arguing With Zombies: Economics, Politics, and the Fight for a Better Future.” The book is a collection of essays the Nobel Prize-winning economist has written about zombie economic ideas — those “that should have been killed by contrary evidence, but instead keep shambling along, eating people’s brains.” (Zombie ideas have popped up regularly in Krugman’s pieces for years but he has said it’s a term he first saw in the context of myths about Canadian health care.”)

The most persistent economic zombie, according to Krugman, is “the insistence that taxing the wealthy is hugely destructive to the economy as a whole so that cutting taxes on high incomes will produce miraculous economic growth.

“This doctrine keeps failing in practice,” Krugman says. So, it’s either an economic myth that’s perpetuated or a proven policy that’s maintained, depending on your vantage point. Krugman and others would argue those who see it as the latter are ignoring the facts.

A $2.8 billion expansion of Interstate 10 was completed in 2008, making the freeway the widest in the world: 26 lanes across at Beltway 8.

Traffic can be a nightmare and there are zombies too

Similarly, despite data and evidence that indicate road expansions don’t effectively reduce congestion — in fact, they only seem to encourage more driving — the solution to gridlock too often is increased capacity. While that makes intuitive sense, widening and expanding hasn’t proven to be a sustainable solution for improving traffic flow.

The urban highway expansion is a zombie policy, Higashide says.

“We know that (highway expansion) doesn’t work but it keeps getting resurrected anyway.”

“We can we can see that highways separate neighborhoods and actually, in a lot of ways, make access worse if you’re looking at local trips and transit has a lot of potential to improve connections instead.”

Higashide is the director of research for TransitCenter, an advocacy group that promotes improved transit in cities across the country. On. Feb. 12, he’ll be the featured author at the Kinder Institute’s Urban Reads series, where he’ll discuss “Better Buses, Better Cities.”

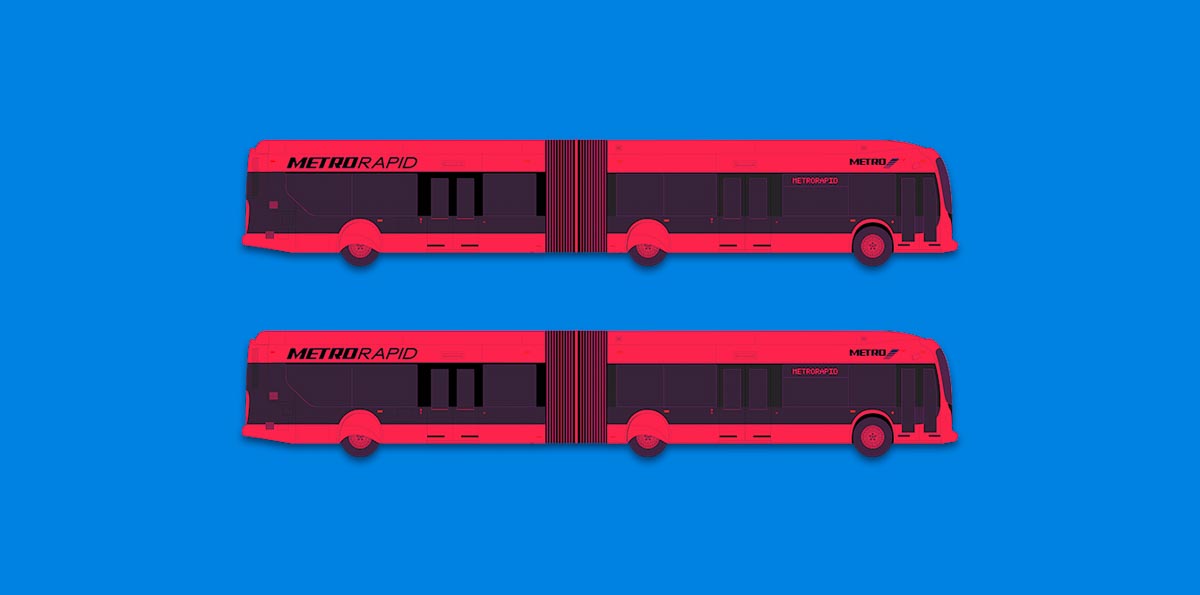

In it, he writes about Houston Metro’s bus network redesign in 2015 — a complete and overnight overhaul of the agency’s route system. Higashide praises the “blank-slate” approach taken by Metro and its strategic planning committee. The effectiveness and success of the new network have made it an example for other cities.

“(The network design) has been hugely inspirational to transit agencies around the country, and really demonstrates the importance of frequent bus service and the importance of redesigning a network so that it responds to changes in how the city has developed,” Higashide says. “When you look at why bus ridership has declined in most places, you often see bus networks that have stood still as the city has changed around them. And what’s so compelling about the Houston redesign is the realization that the job centers are different than they were years ago and that people live in different places. The network has to respond and change to meet those changes.”

Often overlooked and disparaged, buses, Higashide argues, are an important driver of equity and environmental sustainability, and help cities succeed.

“Buses are an essential ingredient in public transit networks that work for cities, and you really can’t have a world-class transportation system or a world-class transit system, if you don’t have bus service that is frequent, fast, reliable, and safe.”

What can other cities learn from Metro?

Metro’s redesign, which transformed a spoke-and-hub route system focused primarily on the city’s downtown into a wider grid, has become a model for transit agencies in other cities, but Higashide also points out Metro’s comprehensive strategic plan as an example for others.

“Houston Metro had a political plan that was as strong as the transit plan,” he says. “They had very strong early stakeholder outreach. They had very strong outreach to political leaders throughout the region. And they built an internal team that could deliver on the redesign with urgency.”

Without top-down buy-in and total collaboration from the entire organization, he says, they couldn’t have pulled off the implementation.

“It wasn’t a siloed effort. Every department in Metro was involved and had to be involved. Those are really important lessons for other cities.”

What can Metro learn from others?

As most know, walkability isn’t one of Houston’s strengths.

Higashide emphasizes the direct and unambiguous relationship between transit experience and pedestrian experience. If one is lousy, it can undo the other and ruin the entire experience. It doesn’t matter how fast, frequent and on time the buses run if riders have to cross unsafe roads to reach a bus stop that’s not sheltered, then wait on the side of the road without protection from traffic.

“If there’s no sidewalk, if there’s no shelter, it’s not going to be a great transit experience,” Higashide says. “Transit agencies don’t control sidewalk funding, typically, but there’s an incredibly clear and important connection. And so thinking about what transit agencies and what local government can do to (address the deficiencies) is so important.”

He points to TriMet in Portland and Washington State’s King County Metro as transit agencies that have effectively lobbied and engaged local governments for the coordination of investments in transit and infrastructure that impact pedestrians.

Only about a quarter of the bus stops in Houston are covered but the agency’s METRONext Moving Forward Plan includes funds allocated for bus stop improvements such as shelters and new or improved transit centers, as well as improvements that address the first mile and last mile of a rider’s commute.

“Sometimes in the transit industry, bus shelters are described as an amenity but I think that undersells the importance of shelters. There’s very clear research showing that when a bus stop doesn’t have a shelter, a bench or real-time information, the wait can feel two and a half times longer than it actually is — or even longer. If transit agencies offer shelters and benches and real-time information, perception lines up with reality again.”

Higashide had a lot to say about the state of public transit in the Houston area today and the potential for a better future, including taking advantage of the current momentum to ensure continued improvements and the importance of ensuring access to transit is equitable.

On METRONext and the future of Metro:

“One of the things that’s really impressive about Houston is the way in which bus improvements have built momentum for future improvements. The bus network redesign is a strong foundation that has helped establish Houston Metro as a credible agency. And I suspect that’s one of the reasons why METRONext was successful at the polls.

And even as the transit agency is implementing MetroNext, it’s time to ask what comes after that? And I think that that leads to a question about how do you eventually expand the budget for operations at Houston Metro? Houston Metro is delivering a lot of great outcomes and delivering a lot of benefits to this region. So how do you keep the momentum going? That is an advocacy question. And a political question.”

On the expansion of fare options:

Higashide advocates for making paying for transit more equitable and easier. He’s for fare-capping, eliminating charges for transfers and expanding ways to pay for fares.

“It’s especially important that transit agencies focus on the customer experience and think about how to take friction out of the transit experience,” he says.

To decrease friction, many transit agencies are upgrading fare collection systems with options that enable riders to pay bus and train fares with the wave of a contactless credit card or a smartphone using Apple Pay and Google Pay. Metro is considering such an upgrade but for now, riders can only use Q cards, cash or Metro’s smartphone app to pay fares. These upgrades also make it possible to introduce all-door boarding — another time-saver.

“These are all things that take some friction out of the customer experience.”

But the experience of all customers, no matter their socio-economic status, has to be considered by transit agencies.

“If you’re someone who doesn’t have a smartphone or who has a limited data plan, what (transit agencies) do in terms of having a really strong retail network so people have multiple locations where they can buy a transit pass,” he says. “How do you make sure there aren’t punitive fees for those paying with cash. And how do you implement policies like fare-capping, which would mean that whether you pay by the ride or with a monthly pass, no one pays more than the cost of the monthly pass. That’s an important policy because the status quo often is that if you pay by the ride, you end up paying more than someone who uses a monthly pass. (That results in) lower-income transit riders sometimes paying more than those who can afford to put down money ‘for a monthly pass.’”

He also contends riders shouldn’t be charged for transfers between buses, a policy he calls arbitrary and an “anachronistic kind of extortion” akin to Amazon charging customers a restocking fee for canceling a streaming purchase.

Higashide is likely to discuss these ideas and more during his Urban Reads appearance. He’s less likely to talk about zombies or zombie ideas but we can continue the conversation here on the Urban Edge. What are your “favorite” misconceptions or myths that have evolved into accepted truths? We’d love to hear from you. If you'd like to share your thoughts, please shoot me an email.