Last week, the European Union released details of a proposed law that would require companies to make gender pay gaps public and provide salary information to job candidates in the interview process.

The New York Times reported the proposed law would also “empower women to verify if they are being fairly compensated in comparison with male colleagues. The European Commission, the bloc’s executive arm, wants to provide workers with the ability to seek proper compensation in case of discrimination.”

According to the European Commission, there’s a 14% pay gap between men and women doing the same work, and a 30% difference in pensions.

Women in the U.S. face a larger pay gap — about 18.5% — and earn approximately 81 cents for every dollar earned by a man. Between 1979 and 2004, according to earnings data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), women’s earnings as a percentage of men’s rose steadily, from 62% to almost 80.5% before plateauing in 2004. Since then, the earnings ratio has remained stuck in the 80–83% range.

That’s on par with the gender wage gap in the U.S. tech industry, which has gender and racial equity problems of its own. On average, women tech workers in America make 83 cents for every dollar that their male counterparts earn, according to the personal finance technology company SmartAsset, which released its list of “Best Cities for Women in Tech” in February.

According to the study, the city with the worst pay gap is Salt Lake City, where women make only 68% of what men make. Long Beach is the only city where women earn (slightly) more than men — making $1.01 for every dollar their male tech workers earn. The annual analysis ranks cities with populations of 200,000 or more based on the gender pay gap, income after housing costs, tech jobs filled by women and three-year tech employment growth.

In Houston — No. 7 on the 2021 list — the gender pay gap for women tech workers is the sixth-smallest in the nation. Women in the industry here make 94 cents for every dollar their male co-workers earn; and 27.2% of the city’s tech workforce is made up of women — a 17% employment growth from 2016 to 2019. After housing costs, the median income for women tech workers in Houston is $61,016. That’s the 13th-highest overall but a 5% decrease compared to the year before, when the city was No. 6 on SmartAsset’s list. During that time, the gender pay gap increased 5%. However, the number of tech jobs held by women went up about 2%, as did tech employment growth in city.

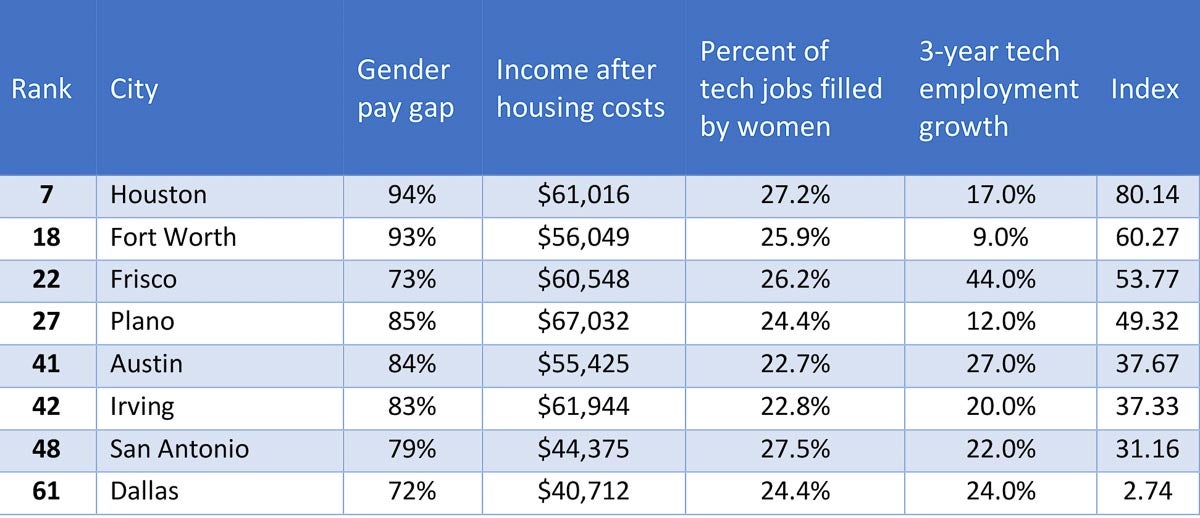

In Austin, the city in Texas best-known for tech, women hold 22.7% of jobs in the industry and make 84 cents per dollar earned by male peers. The median income for women tech workers in Austin is $55,425 after housing costs. Here’s a look at how other Texas cities on the list compared:

Data source: SmartAsset analysis of 2019 5-year American Community Survey data

How can we close the gap?

What can be done to address the persistent — and worsening — discrepancy in pay for women tech workers in Houston, which has a smaller wage gap compared to other cities and is a strong market overall for STEM careers — science, technology, engineering and math?

“This problem is multifaceted and has deep, underlying and systemic roots,” said Christine Galib, senior director of programs at The Ion, an innovation hub in Houston. “So, it’s not just about narrowing the pay gap, it’s also about a better understanding of the barriers women experience prior to and during employment — as well as including women in conversations that generate actionable recommendations from that understanding. Reallocating budget dollars to ensure that those recommendations become reality is crucial. With an inclusive and creative systems-thinking approach, this reality can happen.”

To ensure systemic change takes root and organizational change happens, gender parity in the boardroom is a good place to start, according to Galib.

“But to me, that’s only the beginning,” she said. “We need to hold boards, decision-makers, department heads and employees at all levels accountable not only to develop a talent pipeline and recruit from it, but also to ensure that women are supported and recognized for their contributions at work. This starts with empowering organizational leaders and equipping them with the tools they need to create cultures that reflect these priorities. In this way, we attract, hire, train and showcase talent, thereby retaining it.”

COVID-19 has only worsened the problem

The data used in the SmartAsset ranking of best cities for women in tech are from the Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey, which means it’s possible the pay gaps seen will increase when next year’s list comes out. That’s because, while progress has been made in the past 10 years to narrow the gender pay gap, the COVID-19 pandemic is threatening to undo those advances.

PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Women in Work Index for 2020 shows the disproportionate impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on women compared to men. Based on analysis of employment data across 33 developed countries, the index shows the pandemic has widened the already unequal burden of care shouldered by women, and caused more women than men to leave the workforce to care for children during this long period of remote learning.

COVID-19 has resulted in what has been called a “she-cession,” and by the end of 2021, the index report warns, it could push the progress for women in work back to 2017 levels. In the fourth quarter of last year, women workers nationwide earned $178 less per week than men (83.4%), the Department of Labor reported. That divide increased to $297 for Black women and $366 for Hispanic women.

“While the impacts are being felt by everyone across the globe, we are seeing women exiting the workforce at a faster rate than men,” said Bhushan Sethi, joint global leader of People and Organization at PwC. “Women carry a heavier burden than men of unpaid care and domestic work. This has increased during the pandemic, and it is limiting women’s time and options to contribute to the economy.”

Many mothers left paid work early in the pandemic when schools closed and kids were at home. Last April, almost half (45%) of mothers of school-age children were not working, an analysis of census data released earlier this month shows. The share of mothers actively working dropped 21% while the share of fathers declined 14.7%, compared to March 2020 and the same month the previous year. Even as remote learning began, caregiving and education responsibilities remained high — and mothers were more likely than fathers to leave paid work to handle those responsibilities.

The female unemployment rate in the U.S. jumped from 4% in March 2020 to 16% in April 2020. It remained high for the rest of 2020, ending the year at 6.7% — still 3% higher than December 2019, but the same rate as men.

By January of this year, over 18.5 million mothers living with school-aged children were working — 1.6 million fewer than in January 2020 — according to the analysis. Meanwhile, only about a quarter of children in the U.S. have returned to school full time, meaning child care responsibilities haven’t eased up for many parents. As a result, in many households, working mothers are back to juggling workplace responsibilities in addition to a larger share of household and caregiving work at home.

It’s a continuation of the gender inequality problems that existed before the pandemic, and have been worsened by it. Whether a woman is forced out of work or chooses to stop working during the pandemic, the result reduces earnings, both now and in the future in terms of career disruptions and delays in advancement.

Increasing the share of tech jobs for women

Employment projections from the Labor Department show STEM jobs will grow 8% by 2029, compared with 3.7% for all occupations. However, women workers currently account for just 22% of STEM careers, and less than 10% of engineering jobs.

In the next decade, computer occupations are expected to increase 11.5%. Computer and information technology jobs such as those in cloud computing, big data storage and collection and information security, on average, offer much higher salaries than other industries — in 2019, the median salary of $88,240 was $48,430 higher than the median annual income for all jobs. In Houston, where women fill just over 27% of tech jobs, steps can be taken to increase that share by making sure women are prepared for tech and other STEM careers.

“This can be done by building awareness, providing opportunities for education and training, and illuminating the pathways to make careers in tech possible — and accessible — no matter if you are 5, 15, or 50,” Galib said. “This starts with our youngest Houstonians.”

An example of this is Family Tech Night, a new series designed to help individuals, particularly women, build tech and digital literacy and awareness that a career in tech is possible. The series, which kicks off on March 23 with Melecia McLean, managing director of Girls in Tech–Houston, also connects participants with subject-matter experts to help them build their network and — potentially — find mentors.

Mentoring — described by Galib as a two-way street — is another key piece of bringing more women to the tech industry.

“Finding women mentors and then paying it forward to be a mentor yourself helps ensure that we are creating the relationships that champion the change we want to see,” she said. ”Knowing who your advocates and allies are is also a crucial step to increasing the share of tech jobs filled by women.”