Bill Fulton, director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, wrote about Houston’s famous lack of zoning for the latest issue of American Planning Association’s Planning Magazine, which is filled with stories about the city.

While mostly and technically true — yes, it has no zoning for use — over time the line between caricature and reality has blurred for many who are outside of the city limits looking in. (Actually, that’s the case with a lot of popular misconceptions about Houston.)

It’s a little like “Houston, we have a problem,” the well-known but misquoted line from the Apollo 13 spaceflight. By now, thanks to the Comic Book Guys of the world, most of us are well aware that what Astronaut John Swigert actually said back in 1970 was, “OK, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” Followed by Astronaut Jim Lovell’s “Uh, Houston, we’ve had a problem.” The inaccurate quote doesn’t change the gist, plus it’s a lot less clunky as a soundbite. In reality, life for Bayou City developers isn’t an endless laissez-faire free-for-all. As Fulton puts it: “A city without zoning … isn’t necessarily a city without planning.”

Here’s a rundown of the article, which can be read it in its entirety on the American Planning Association’s website.

It’s complicated: There may not be zoning but there are restrictions

Houston is the fourth-largest city in America, with a population of 2.3 million people spread across more than 600 square miles. It contains some of the densest job centers and ritziest residential neighborhoods in the country. Yet three times in the last century — most recently in 1993 — Houstonians have voted down that most elemental of planning policies: zoning based on use. It’s the first thing any planner — indeed, almost any person — asks about when they ask about Houston.

A city without zoning, however, isn’t necessarily a city without planning. Or without a frustrating development code. Or, in a certain way, even without zoning.

The story of Houston’s land-use policies is a lot more complicated than “no zoning.” In reality, Houston is a big mixture of ordinances, policies, tactics by neighborhoods, and independent efforts by nonprofits, all of which play a role in determining how land is used. Whether or not the lack of zoning and the use of these other tools add up to a more equitable city or a city where the affluent are protected is open to debate.

Here’s how land use is addressed in Houston

The city is rife with plans, strategies, and other efforts to create more walkability, bring new investment into historically underserved communities, and protect the city against future flooding and other hazards. For many years, the region’s metropolitan planning organization, the Houston-Galveston Area Council, has conducted Livable Centers studies to show the potential for walkable neighborhoods, while at the same time the city has engaged community leaders and planning commissioners in an effort to create more walkable places. Mayor Sylvester Turner’s signature neighborhood effort is Complete Communities, focused on directing city resources to underserved neighborhoods. And most recently, Houston joined the 100 Resilient Cities network, thanks to a grant from Shell, and is crafting plans to improve the city’s resilience.

At its core, however, Houston’s land-use regime boils down to three separate types of efforts.

1. Large-scale initiatives to shape the public realm, usually undertaken by philanthropists and civic groups. (Alongside these are some public-sector efforts to create plans around specific topics.)

2. A series of planning tools that act as zoning workarounds, ranging from deed covenants to historic districts.

3. A complicated development code that contains everything you’d expect except use zoning — and, in some cases, density and height restrictions as well — and drives applicants crazy just like the development code in many other cities.

Ways to circumvent a lack of zoning

The biggest difference, of course, is the lack of zoning — but what that really means in Houston is that there is no zoning for use. Under the city’s development code, no parcel of land is restricted for any particular land use, and in many cases, there are no density or height restrictions either. But what most Houstonians in the know understand is that the city is not entirely without zoning-type regulations.

► Virtually every affluent residential neighborhood in Houston has strict private deed restrictions — and, remarkably many of those deed restrictions can be enforced by the city. That’s why River Oaks, Houston’s wealthiest neighborhood, doesn’t have apartment buildings or office buildings in the middle of the neighborhood.

► Deed restrictions are not enforced unless complaints are reported, meaning that less affluent neighborhoods often see covenants violated if the residents are not vigilant. Developers are constantly on the lookout for the one parcel in a desirable location that isn’t covered by the deed restrictions. This is the loophole that led a few years ago to the well-known “Ashby high-rise” fight, during which affluent residents went to court to fight a proposed high-rise apartment building on Ashby Street near Rice University.

► Then there are historic districts. The trend began in the early 2000s (there are now 22 total) with the creation of three historic districts in Houston Heights, a bungalow neighborhood northwest of downtown Houston. When the Heights gentrified, it attracted the attention of apartment developers. In response, residents petitioned for the creation of historic districts, which require that the scale and character of the neighborhood remain the same. Some neighborhoods are in effect using historic districts as a zoning substitute.

Other substitutes for zoning

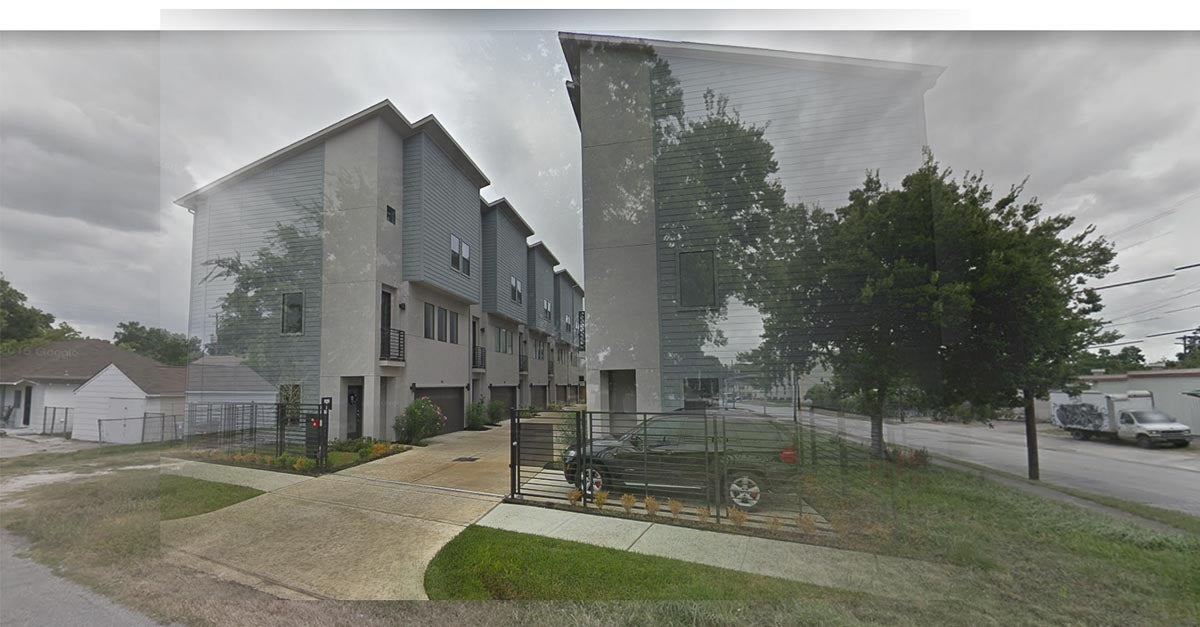

Several years ago, the city also created a process by which residents and neighborhoods could petition for a minimum lot size or minimum building line, or setback from the street. This allowed for the circumvention of a 2001 ordinance that dramatically decreased minimum lot size inside the 610 Loop, opening up huge chunks of the central city to townhome development. These processes help to eliminate the possibility of townhome development by gathering support from a majority of area property owners and the passage of an ordinance by the city council.

A few years ago, affluent residents went to court to fight the construction of a high-rise apartment building dubbed the “Tower of Traffic” at the corner of Ashby and Bissonnet streets near Rice University. The land the developers wanted to build on wasn’t protected by deed restrictions. The residents who oppose unwanted change in many neighborhoods don’t have the resources to take on developers.

Market-driven development is the reality in Houston

Land deals in Houston were once negotiated between politicians and landowners in the Rice Hotel. Open government laws have long since ended that practice, but the development community continues to influence city regulations.

As for the development code itself, Houston does have one, perhaps contrary to popular belief. It just doesn’t have use restrictions and in some cases height and density restrictions. As a result, Joshua Sanders, a local development lobbyist, calls it “a bad form-based code.”

The result is a more market-based approach to development, especially in gentrifying neighborhoods. On Montrose Boulevard, for example, two 30-story apartment towers have recently been built in a traditionally one- and two-story neighborhood, adjacent to duplexes and one-story retail and restaurant buildings. The same is true along Main Street in Midtown, alongside Houston METRO’s Red Line, one of the busiest light-rail lines in the country.

It also means affordable-housing developers have a tough time competing for land because they are competing against high-rise residential developers and high-end retail and restaurant developers, and whoever else can bring the most money to bear on a parcel.

Developers built eight townhomes at the corner of McKinney and St. Augustine streets in the East End. The homes are less than a 10-minute walk from the Coffee Plant/Second Ward stop on the light rail’s Green Line.

Efforts to bring more affordable options to neighborhoods

There are some promising approaches that could make more affordable land and units available, however. The Houston Land Bank was recently reorganized and is now working to reuse tax-delinquent properties it acquires for the public good, including affordable housing. In 2018, the nonprofit Houston Community Land Trust launched, with a mission to build long-term affordable home ownership.

Like the development code in most cities, Houston’s code is big, complicated to administer, and in many ways inflexible. In almost all locations in the city, for example, development must provide a 25-foot setback from the street and ample parking requirements. On the other hand, there are no parking requirements in Downtown Houston or in certain parts of Midtown, an adjacent gentrifying neighborhood. Near transit lines, developers are eligible to use an optional transit-oriented development code, but the incentives contained in this ordinance are perceived by developers as modest — a 15-foot setback instead of a 25-foot setback, for example. Most developers in the urban core opt instead to shoot for variances. The city planning commission typically grants setback variances, but not parking variances, leading to gigantic parking garages even in the most urban neighborhoods. (The planning commission’s Walkable Places Committee, mentioned above, is looking at ways to beef up the TOD ordinance.)

Despite the lack of traditional zoning and the jumble of other regulations, it’s surprising how well Houston works. It’s a big, dynamic city that doesn’t look or feel that much different from, say, Los Angeles or Dallas. As most other cities are these days, it’s a city of haves and have-nots — and the lack of zoning cuts both ways on that issue.

And, with the revival of large-scale public realm planning, especially dealing with greenways, Houston is beginning to gain a strong sense of itself that has always been lacking. Even without zoning, Houston is becoming a better and better urban place every day.