Houston METRO’s investments into transportation infrastructure such as light rail stations and transit centers are impacting the way land is used in the communities surrounding them. The shifts are especially notable in areas that previous Kinder Institute research has shown to be undergoing significant redevelopment and gentrification.

The institute’s latest report on transit adjacent development examines changes in land use within 1 mile of major transit hubs between 2010 and 2016. A key finding of the research is the discovery that the vast majority of land-use change in many gentrifying communities is occurring along transit lines and near key stations. And all signs point to continued redevelopment.

Advantages of transit investment can lead to disadvantages

The fact that land use is changing around transit is not surprising.

To a great extent, the effects a transit line or hub can have on real estate patterns in the surrounding areas are a major justification for building the line in the first place. Moreover, transit investments can help reinvigorate and reconnect neighborhoods. The systems are, most importantly, critical to ensuring residents can access opportunities.

However, these positives should be weighed alongside the changes transit investment, among other factors, can spur, especially if it results in longtime residents being displaced. Too often transit investments are not combined with additional tools and policies to slow or prevent displacement. In most cases such policies are beyond the purview of a transit agency to implement alone, and comprehensive, coordinated responses are rarely pursued.

The rapid redevelopment of vulnerable transit-adjacent areas is problematic because many of these areas continue to provide lower-cost homes and have populations with lower incomes. As those areas are redeveloped, housing costs, including property taxes, go up, contributing to some residents being priced out of the area.

Change comes quicker to TAD areas that are gentrifying

There have been increases in the number of commercial and single-family lots in all of Houston’s transit-adjacent areas, but those that are gentrifying have seen these shifts happen most frequently. Much of the change happened as land previously used for industrial purposes is used for commercial and residential purposes when amenities and mixed-use buildings were added along transit.

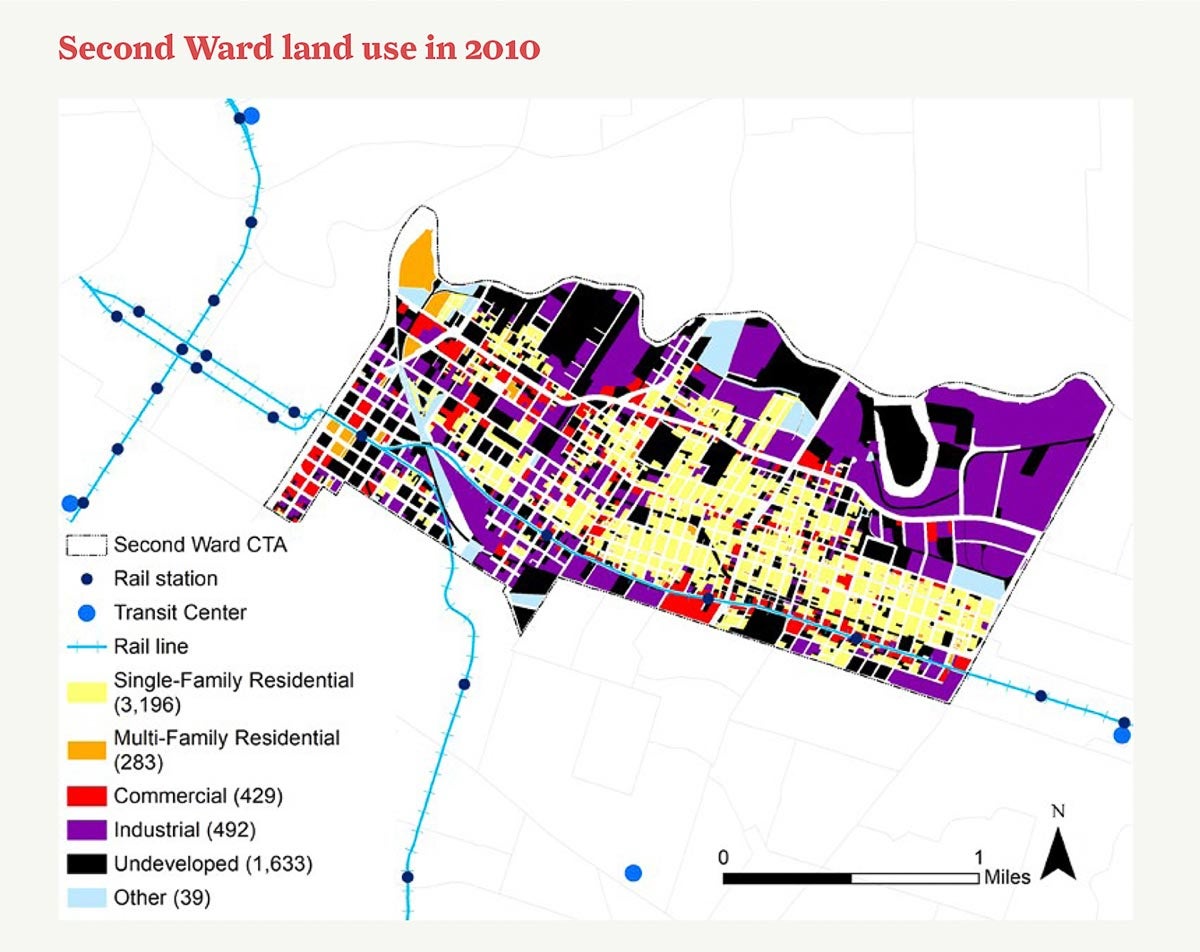

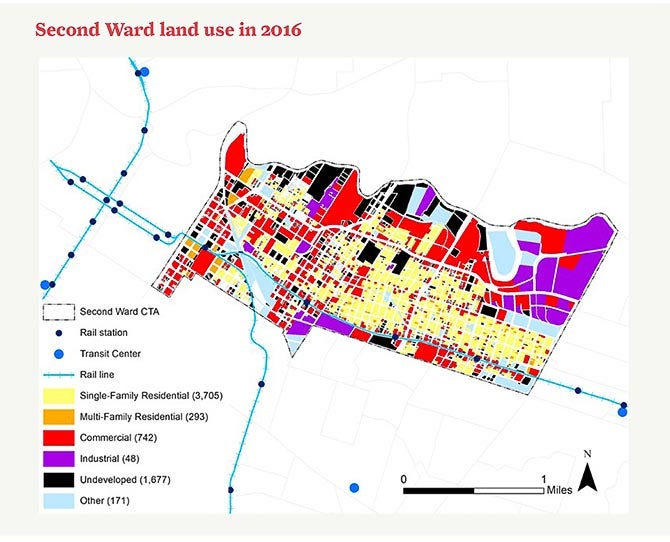

Gentrifying transit-adjacent areas saw single-family lots turn into undeveloped lots or be replatted into multiple smaller lots at higher rates than other transit-adjacent areas, a signal that additional redevelopment is likely. Some of these shifts are visible in the Second Ward, one of the neighborhoods studied in the report. A clear shift toward commercial use along the light rail’s Green Line can be seen in these images from the report:

Source: Transit Adjacent Development and Neighborhood Change in Houston

What factors determine vulnerability to gentrification?

Transit-adjacent areas less likely to gentrify — areas that tended to be wealthier and more white — also saw changes over the period of study. However, most of the changes in these areas were toward more residential use. Put another way, wealthier and predominately residential transit-adjacent areas remained predominately residential even as their land use changed. Unlike gentrifying areas, these communities saw less commercial and multifamily development.

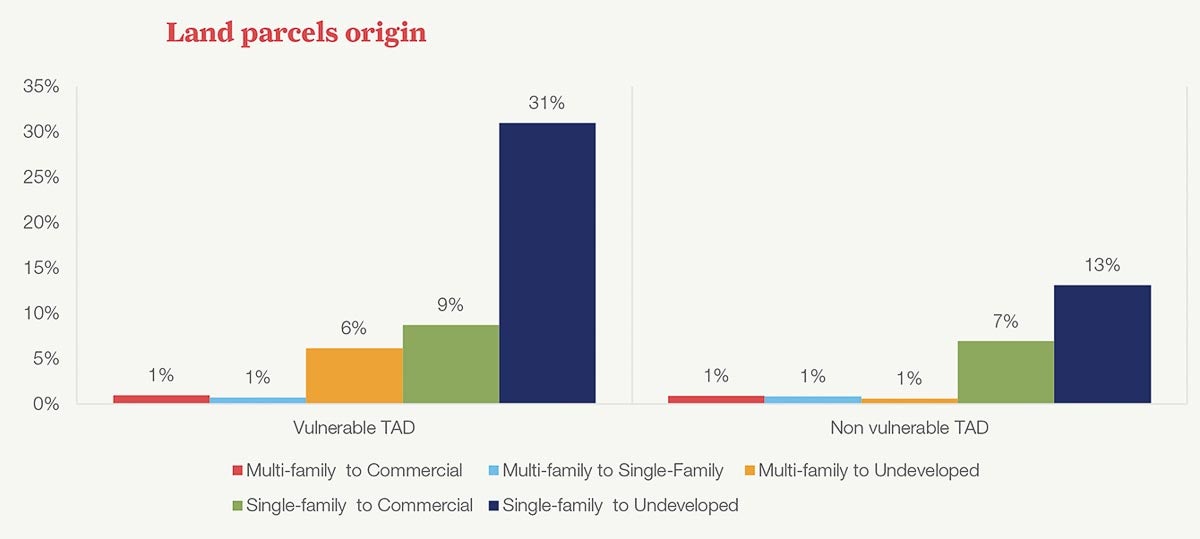

This distinction is visible in the figure below, which compares changes in land use for transit-adjacent areas that are vulnerable to gentrification with those that aren’t. Between 2010 and 2016, a huge percentage of lots in vulnerable areas shifted from single-family to undeveloped, signaling a likely demolition. There was a smaller, but significant, shift of multifamily lots to undeveloped lots. This can be particularly problematic because it can indicate the loss of multiple more-affordable multifamily units. Both of these shifts are representative of the redevelopment quickly remaking gentrifying areas. The non-gentrifying transit-adjacent areas also see shifts from single-family to undeveloped lots, but at a much lower percentage.

Source: Transit Adjacent Development and Neighborhood Change in Houston

Transit investments need to benefit all involved

METRO’s transit investments are critical to building an interconnected and effective transit system. But as those investments are made, the ties between development and transportation must also be considered to ensure all residents gain from the benefit of those investments.

While transit is not the only catalyst for redevelopment, it certainly plays a role in driving land-use change. Public transit agencies should work with both public and private housing developers to bring multiple levels of affordability into areas where investments are being made in innovative ways.

Houston and Harris County currently have the chance to use the Harvey Disaster Recovery Funds to focus on housing investments that are well connected to transit. Beyond single investments, though, broader policies such as tax abatements or community land trusts can be used to help keep longtime residents in communities as they change.