The “Re-Taking Stock” report recently released by the Kinder Institute for Urban Research is quite something. Packed with useful information and an abundance of beautifully executed maps and graphics, the report documents how Houston’s housing stock has changed in the 21st century, and how those changes relate to changes in the city’s neighborhoods.

As an academic who both engages in and avidly consumes this type of research, I know it’s a big task to combine data from hundreds of thousands of property tax records with census data, which was the only way the Kinder Institute could carry out this kind of analysis. It’s a reminder that Houston is lucky to have such a research powerhouse squarely focused on tracking the city’s evolution into the world’s energy capital and now the most ethnically diverse big city in America, or close to it at any rate.

Editor’s note: This is the third post in a four-part series on the Kinder Institute for Urban Research’s new report, “Re-Taking Stock: Understanding the Connections between Housing Trends and Gentrification in Harris County.” The report connects housing stock changes with gentrification risk in Harris County.

As I devoured the report, three things really stood out for me. First of all — big picture — something is really going right in Houston with its housing growth patterns. Any city has problems when you look at it under the microscope, and Houston is no exception, but that can also cause us to lose sight of things that are positive. Houston is doing things that most other big U.S. cities’ political establishments say they want to achieve, but unlike most other places, in Houston, the talk is actually being matched with results on the ground. But, that doesn’t mean Houston is a Shangri-La for housing. As the report shows so well, the city’s neighborhoods are evolving in different ways that are highly complex and tough to summarize with a single catchphrase.

That brings me to my second observation: gentrification. Although, in my view, still a useful concept, the term gentrification has come to so thoroughly dominate discourse about growing U.S. cities that it flattens out a lot of the complexity and variety driving the ways in which neighborhoods in cities are changing. The sophisticated analysis in “Re-Taking Stock” makes it possible to tell a more nuanced — and ultimately richer — story of the city’s evolution in its fullness.

And, finally, even if there is a lot to celebrate regarding Houston’s growth patterns, and even if gentrification is not the only problem the city’s vulnerable residents face — far from it — those residents still face a lot of housing-related challenges. The Houston story shows the limitations of what simply allowing housing, which Houston has done better than just about anywhere else, can do. The silver lining here is that Houston’s unique system of regulating housing may allow for some unusual strategies that could help safeguard its historically disenfranchised populations and vulnerable newcomers alike. But it’s going to take some serious effort and taxpayer dollars, and it won’t happen overnight.

‘Smart Growth’ without even knowing it

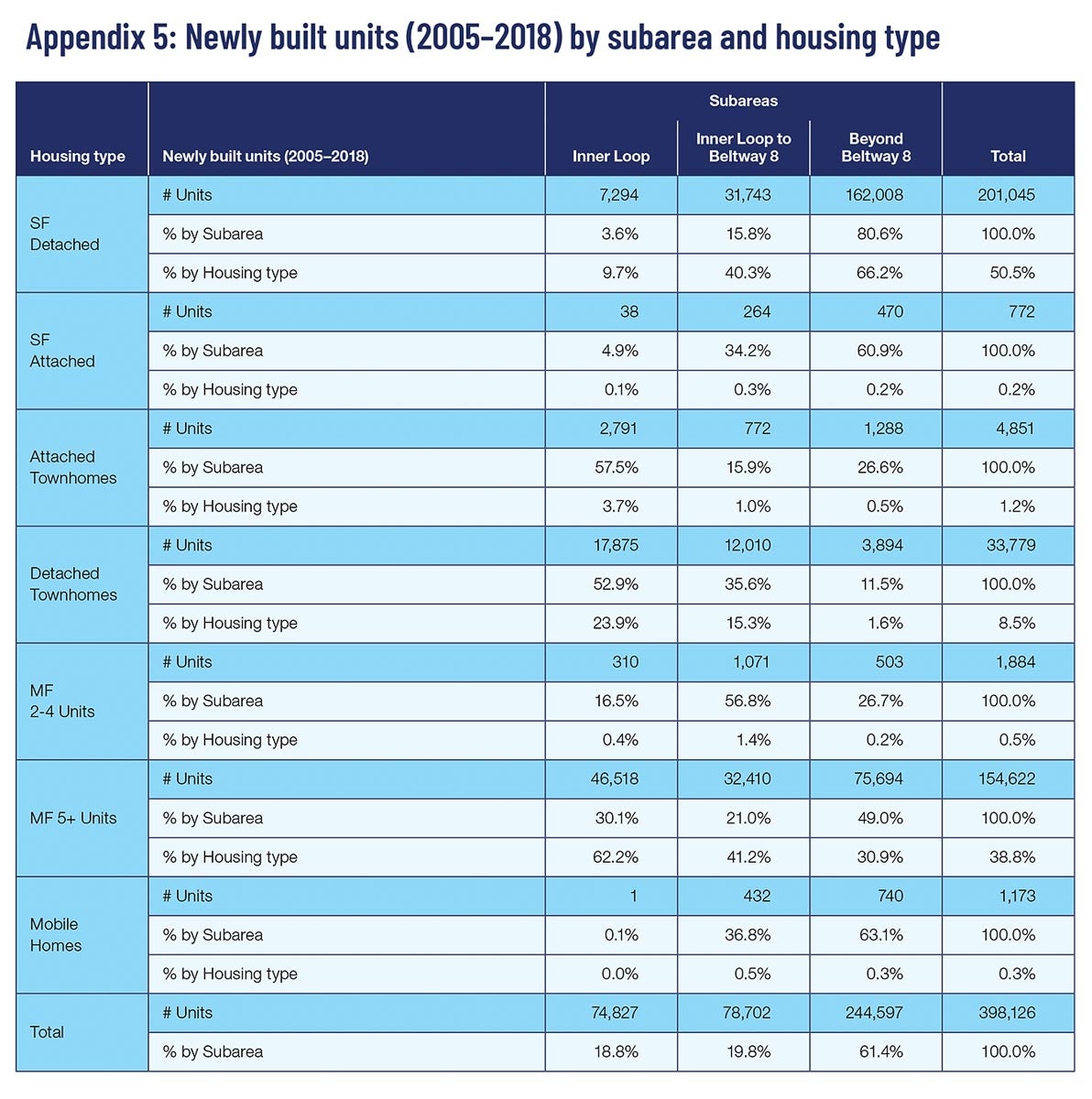

Let me dig into each of these three points a little more in turn. First, the unambiguously good stuff. If you think of Houston’s Inner Loop (the area inside Interstate 610) as equivalent to a decent-sized U.S. city, the “Re-Taking Stock” authors observe that the area is growing faster than many other hot-market U.S. cities of equivalent size, and capturing a pretty healthy share of the overall region’s growth. Appendix 5 shows the construction of a whopping almost 75,000 units inside the Loop in just the 13 years leading up to 2018 — almost a fifth of the countywide total on just 5% of the land. That’s really great! Houston’s urban core is flourishing, with new residents, expanding public transportation, abundant and expanding cultural attractions, and all of the other good things that happen when a downtown and its surrounding neighborhoods regain vitality and commerce after decades of nonstop suburbanization.

Urban planning wonk types (I plead guilty to being one of them) sometimes call this aspiration “Smart Growth.” My sense is that Smart Growth isn’t a big part of the discourse in Houston, but I’m struck by how Houston is getting it done — at least the “thickening up of the urban core” part, if maybe not the “restraining suburban sprawl” part — in a way that a lot of other cities aren’t.

More broadly, something must be going right in Houston given that it is one of just a handful of big cities that is a net attractor of African American migrants from elsewhere in the U.S., and of immigrants from pretty much everywhere in the world. People vote with their feet in search of opportunity, and the places they are drawn to generally have something to recommend them. Housing isn’t the whole story here, of course, but home prices that are strikingly low for a jobs-rich city surely don’t hurt. Five of the seven “Re-Taking Stock” case study neighborhoods have median home prices that are easily within reach of middle-income homebuyers. The two others, Montrose and Lazybrook/Timbergrove, are still fairly inexpensive compared to similarly situated, high-amenity neighborhoods near downtown in other big cities. (I should mention here that rental-housing affordability is a much less encouraging story — but more on that later.)

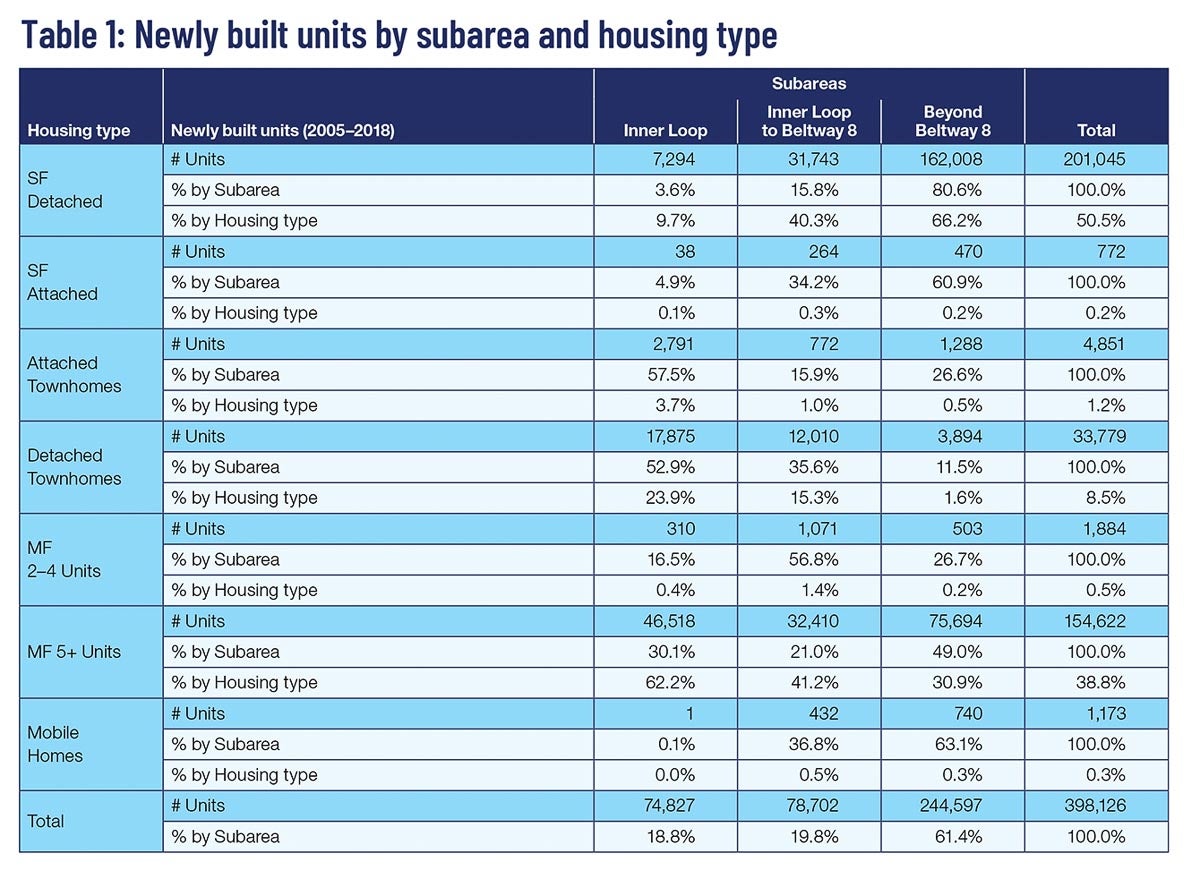

Source: Kinder Institute’s “Re-Taking Stock: Understanding How Trends in the Housing Stock and Gentrification are connected in Houston and Harris County”

When gentrifiers are gentrified

That’s the big picture. But what about when you get into what’s happening in individual neighborhoods? “Re-Taking Stock” shows that there is a lot going on, and it’s hard to sum it all up neatly, because it’s highly varied. One of the seven featured neighborhoods, Third Ward, looks like a classic case of gentrification, with a proudly majority-Black, downtown-adjacent neighborhood now being transformed by an influx of mostly affluent, college-educated whites. Even so, as of 2018, Kinder Institute data shows the neighborhood as still being almost two-thirds African American, so the transformation is not (yet?) as complete as it has been in other famously gentrified neighborhoods such as Central East Austin.

This may be in part because of what Kinder Institute researchers call “gentrifiers being gentrified” in Montrose and in other areas west of downtown and Midtown. That doesn’t happen in most cities. In most booming cities, after the residents of neighborhoods comparable to Montrose reach a certain level of affluence and amenity, they agitate via the local political process to slam the door shut on new development. Part of Houston’s secret sauce is that it makes it a lot harder to halt housing growth, and that applies even in some affluent communities. (Though not impossible — far from it — more on that toward the end.)

A new pattern of young, Hispanic renters

There are other patterns. Fifth Ward, Independence Heights and Sunnyside all exhibit one that is understudied and not sufficiently remarked upon in our urban discourse — the departure of African Americans, who are more likely to be older and homeowners, coupled with the arrival of Latinos, who are more likely to be younger and renters.

This isn’t limited to Houston — you can see it in huge swaths of Los Angeles, for example, including in such iconic (former) Black-majority areas as Watts and Compton. However, in the three Houston examples mentioned above there is much more new construction. I don’t know exactly what to call this pattern, and I’m not sure anyone does at this point, but it’s important and has big implications. It is not, however, gentrification.

New housing, old hazards

Then there’s Spring Southwest. If you just glance at the summary statistics that Kinder Institute researchers pulled together, your first reaction might be that the area is providing abundant housing opportunities, including plentiful new-builds, at a modest cost to many people of color. While that is true, it comes at a cost.

Spring Southwest is distant from downtown and other job centers, but that’s, perhaps, not the biggest issue — after all, generations of previous Americans have sought better housing and other amenities as a tradeoff for longer commutes. The most urgent concern, as the “Re-Taking Stock” authors point out, is that a lot of the new housing in Spring Southwest lies within flood-prone areas. Here we start to see some of the weaknesses of how housing growth happens in Houston. No one who lives there needs to be reminded that the city is prone to various forms of hazards, and that these are intensifying. And yet, the status quo is one where sometimes hardworking people who are just looking for a nice, affordable place to live, and think they’ve found one, end up in harm’s way.

More housing isn’t a panacea

Exposure to natural and manmade hazards, and missing basic amenities in certain neighborhoods — usable parks, grocery stores and much more — are, as the report notes, a knotty challenge. And this brings me to my third and last observation: housing growth can’t solve everything.

Even when you do a much better job of it than almost any other big U.S. city, as Houston does, by allowing a wide variety of housing types to be built with a relative minimum of fuss and expense, you will still end up with a lot of unmet needs. Housing growth, as it turns out, is only the beginning. A really important one, to be sure, but Houston’s working-class communities in particular will need a lot of sustained attention from the city, nonprofits, philanthropies, the business community and their own residents to make sure that a cheap house or affordable apartment can be a launching pad for upward mobility.

Houston has a rent-affordability problem

And I should mention that there is one, across-the-board, really troubling housing trend seen in all seven of the case study neighborhoods: in all of them, the percentage of renters paying more than a comfortable 30% share of their income on rent has gone up since 2000, sometimes by a little, and sometimes by a lot. This mirrors what’s going on across the country. It is not going to turn around without pumping a lot more subsidy dollars into rental housing — there is no way to avoid that. Help may or may not come from the feds — if Houston wants to be sure to make headway, it’s going to have to find a lot more local dollars to put into rental housing. Whether or not gentrification is the main problem bearing on low-income renters in a given neighborhood, rental unaffordability is a problem everywhere, and it’s moving in the wrong direction.

Kinder Institute photo

‘Detached townhomes’ are the city’s secret weapon

But here’s where I end on a high note: Houston’s unique system of regulating housing (less than other places) offers some unique possibilities, maybe not all of which are yet being used to their full potential to solve some of these thorny problems. First of all, the Kinder Institute report makes the diversity of housing types in new construction in Houston abundantly clear. In Austin, by and large, we build huge new apartment buildings, or else we tear down existing single-family houses and replace them with much larger and far more expensive single-family houses, or at best duplexes.

In Houston, what the Kinder Institute calls the “detached townhome” is a real secret weapon for land-efficient, easy-to-build new housing, made with inexpensive wood-framed construction. It is a housing type that’s rare in most cities but close to 34,000 of them were built in Harris County from 2005 to 2018 (Table 1). The detached townhome is versatile — it can be high-end or entry-level, or it can be used for below-market-rate homeownership, or rental for that matter. Maybe some of them could have their ground floors converted to commercial uses someday — that maybe sounds crazy, but that was a routine practice in American cities before zoning existed. (Since Houston never did adopt zoning, is that so crazy to imagine?)

Unlike large apartment buildings, detached townhomes can be built in small increments, on a single residential lot, if necessary. Townhomes may at times read as a symbol of gentrification, but there is no reason why they can’t be a big part of the solution to all sorts of problems stemming from neighborhood change of different kinds.

Opting out of housing growth

The “Re-Taking Stock” report doesn’t mention — hey, not every report can cover everything! — Houston’s well-established system for allowing homeowners to choose to band together and enact private covenants to keep out redevelopment. The orthodox position would be that this is bad and contrary to Houston’s generally pro-housing-growth attitude, but the housing scholars Nolan Gray and Adam Millsap have provocatively (and correctly, in my view) argued that this mechanism is the key to Houston’s success. By essentially allowing the people who most fiercely oppose housing growth in their immediate vicinity to “opt out” — overwhelmingly, the denizens of such tiny enclaves as River Oaks — the path was cleared for Houston’s reforms in the late 1990s, which made the rapid proliferation of detached townhomes possible. Well, fine, but maybe residents who are fearful of being displaced in the wake of gentrification should also consider using this mechanism at a greater rate than they do now. This could be a focus for people already doing organizing work in such communities. Perhaps it’s a case of “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.”

What about mobile homes?

Then there’s one housing type that strikes me as both quite important in Greater Houston’s housing mix, but almost completely absent from the housing growth in the city since the turn of the 20th century. That’s mobile homes — that housing type that is so often stigmatized, completely unfairly in my view. The two big problems with a lot of mobile home parks is that they are often exposed to environmental or other types of hazards, and that mobile home park owners can evict the homeowners with little warning, forcing them to pay thousands of dollars to relocate their homes on short notice or risk losing them, as the scholar Esther Sullivan has written about (with an in-depth look at Harris County) better than anyone. But both of these are completely avoidable. Mobile home parks can be sited in safe locations. And resident-owned cooperatives or nonprofit ownership can make living in a mobile home park a secure way for a homeowner to build equity and plant roots in a community, at a very reasonable price of entry.

So, even if the housing-type diversity in Houston that shines through in the Kinder Institute’s “Re-Taking Stock” report is commendable, maybe there’s scope for even more. Perhaps we’ll find out if Kinder ends up releasing a Re-Taking Stock at 20 follow-up report in the year 2041. (No pressure or anything.) Speaking only for myself, it’ll be worth the wait.

Jake Wegmann is an associate professor in the School of Architecture at The University of Texas at Austin. His research lies at the nexus of housing, real estate development and planning.