“It turned out in hindsight that we have a great number of hospital beds that are vacant, that appear that will not be needed to treat COVID-19 patients,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said at a April 17 press conference when he announced plans for the phased reopening of the state’s economy. “Because of the hospital bed vacancy and because of a new supply chain for PPE, we feel that we can begin allowing some more procedures.”

Two months later, the state is seeing day after day of record-high COVID-19 hospitalizations. The number of confirmed or suspected patients in intensive care unit beds has jumped by 80% in the Houston area, from 273 on Memorial Day to 506 on (June 20), according to the Southeast Texas Regional Advisory Council, the Texas Tribune reported. The increase in cases could exceed capacity for the region’s hospital intensive care units in two weeks, according to data gathered by the Texas Medical Center.

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

On May 1, there had been a total of 9,467 cases of COVID-19 in the Houston Metropolitan Statistical Area; and 194 people had died from the disease. That averaged to 135.3 cases and 2.8 deaths per 100,000 residents.

At that time, the Houston area’s infection rate was No. 30 among the nation’s 53 largest metro areas. The Dallas-Fort Worth and Austin-Round Rock areas had similar rates of infection at 105.4 and 103.8, respectively. San Antonio-New Braunfels had an infection rate of 63.7 — the second-lowest on the list.

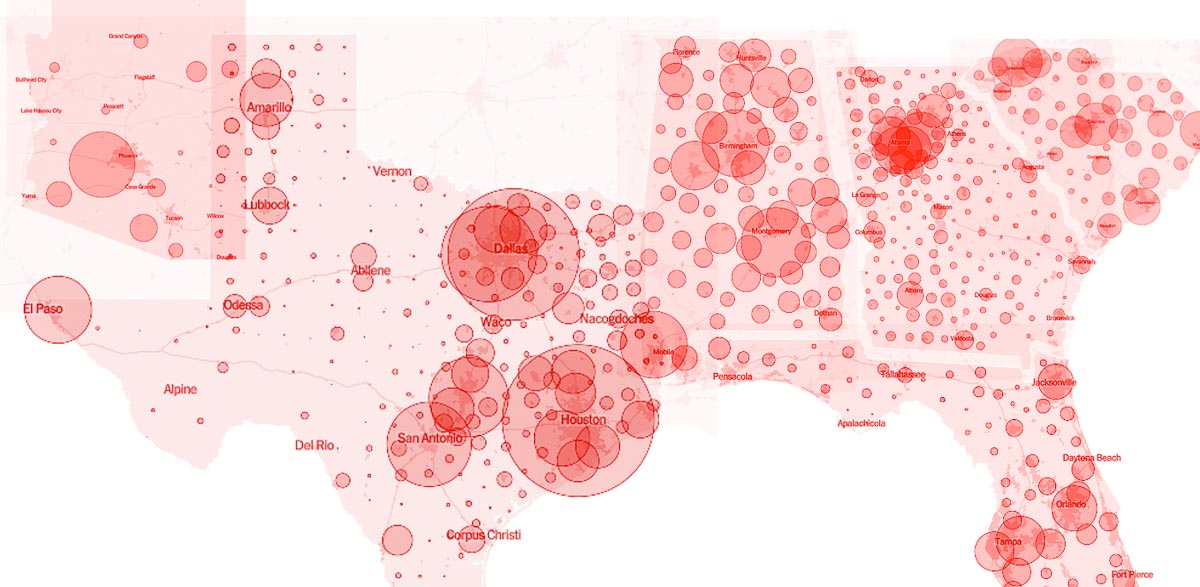

Less than two months later, the San Antonio and Austin metro areas are among the top five metropolitan hotspots in the U.S., according to a CNBC report based on Johns Hopkins School of Public Health data showing the fastest growth in cases between June 11 and June 18. San Antonio was No. 4 and Austin was No. 5, both with the number of cases doubling every 16 days. The double time for the Houston MSA was 26 days — No. 8 on the list — and 29 days for Dallas-Fort Worth — No. 10.

The total confirmed cases and the number of infections per 100,000 residents for the four large Texas metros are:

5,622 cases in the San Antonio area — 223 per 100,000 residents

7,440 cases in the Austin area — 343 per 100,000

25,404 cases the Houston area — 363 per 100,000

28,491 cases in Dallas-Fort Worth — 378 cases per 100,000

A comparison of county-level data from early May and now shows a dramatic increase in the number of cases per 100,000 residents in the nine counties of the Houston MSA: From 160 to 457 in Harris County; 173 to 488 in Brazoria County; 180 to 415 in Fort Bend County; 124 to 280 in Montgomery County; 205 to 571 in Galveston County; 117 to 387 in Chambers County; 74 to 220 in Waller County; 59 to 222 in Liberty County; and 47 to 152 in Austin County.

While some suggest an increase in testing is the reason for the spike in cases, many public health experts say that’s not the case. Though wider testing would result in more confirmed cases, experts say it doesn’t account for the increase in the share of positive results.

The World Health Organization says positivity rates should be below 5%. A low rate of positivity, according to Johns Hopkins’ COVID Tracking Project, may signify a state has sufficient testing capacity for the size of its epidemic. In 11 Sun Belt states, the average of the weekly percent positive is above that threshold: Alabama (9.3%), Arizona (20.4%), Arkansas (5.8%), Florida (11.4%), Georgia (8.3%), Nevada (6.5%), North Carolina (7.3%), Oklahoma (7.2%), South Carolina (10.9%), Tennessee (6.6%) and Texas (10.3%).

Louisiana (3.1%), New Mexico (2.7%), Mississippi (4.6%) and California (4.8%) are below 5%.

“If you test more, you will likely pick up more infections,” Dr. Anthony Fauci told ABC News’ Powerhouse Politics podcast. “Once you see that the percentage is higher, then you’ve really got to be careful, because then you really are seeing additional infections that you weren’t seeing before.”

Metro areas w fastest case growth in last week:

— Meg Tirrell (@megtirrell) June 19, 2020

1. Phoenix

2. Tampa

3. Orlando

4. San Antonio

5. Austin

Largest slowdown:

1. Detroit

2. New Haven

3. Worcester

4. NYC

5. Bridgeport#COVID19

(Via Evercore ISI) pic.twitter.com/TgvC96lp9n

Thirteen of the 15 large metros seeing COVID-19 cases double the fastest are in the Sun Belt region. And Sun Belt states such as Texas, Florida, Arizona, California, South Carolina and Georgia are seeing the nation’s biggest spikes in cases as their economies reopen.

The scene at the Galleria, as described in a recent New York Times story, reveals many may be mistaking “reopening” for “return to normal”:

“At the city’s Galleria mall, there were few signs of concern: People stood in a tightly spaced line for pretzels at an Auntie Anne’s kiosk. At California Nails, two women sat maskless during pedicures. Signs urged social distancing, but in crowded walkways outside stores, shoppers brushed past one another, only inches apart.”

Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo issued an order on June 19 mandating that businesses require their customers to wear masks. The mandate, which follows a similar order from Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff, was put in place to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Over the weekend, however, vaccine researcher and infectious disease specialist Dr. Peter Hotez tweeted that masks “won’t be enough” if things continue in the direction they are now headed:

“My observations if this trajectory persists: 1) Houston would become the worst affected city in the U.S., maybe rival what we're seeing now in Brazil 2) The masks = good 1st step but simply won't be enough 3) We would need to proceed to red alert.”

It’s not clear if Hotez’ tweet was referencing the color-coded threat level system Hidalgo unveiled on June 11. Currently, the county is at level two (orange), meaning residents should “minimize contact with others, avoiding any medium or large gatherings and only visiting permissible businesses that follow public health guidance.”

If moved to level one — the red level — it is recommended that Harris County residents “take action to minimize contacts with others wherever possible and avoid leaving home except for the most essential needs like going to the grocery store for food and medicine.”