Marvin McNeese has lived in University Village for almost 20 years. And in that time, he’s thought a lot about what a park would mean to the small neighborhood in the northeast corner of Greater Third Ward.

Most importantly, a park would be a place close to home where neighborhood kids could safely get together and play after school. That may not sound like a lot, but it’s a stark contrast to where McNeese’s children and others — given no other alternative — have been forced to meet up for a game of catch or to toss a football.

The “Urban Edge Explains …” series explores issues and concepts that are important to cities and their residents. In this story, we look at how the benefits of pocket parks and how one is born.

“Without a park,” he says, “all the kids are playing in the street. One of the first things I had to teach (my kids) is, if you see a car coming, yell ‘car!’ and everybody immediately get to the sidewalk.”

McNeese admits it’s not ideal, but, in his opinion, the impromptu playground is a better option than letting his kids venture out farther from home on their own. Not that he hasn’t ticked off the pros and cons of taking more of a free-range approach to parenting. He considers the kids whose parents let them “roam the neighborhood” to be privileged because they have the opportunity to interact with kids all over the neighborhood, not just those on their block.

“Because of the nature of the neighborhood, people don’t necessarily feel safe letting their kids run everywhere,” he explains. “So, my thought was, if we could get a park, then at least people would feel safe with their kids at the park.”

Like many parts of Greater Third Ward, University Village is a neighborhood in transition — though development is slower than in areas to the west, closer to 288, downtown and the Med Center. It sits immediately northwest of the University of Houston — bounded by Scott Street and Cullen Boulevard to the west and east, and the Gulf Freeway and Elgin Street to the north and south. From above it’s a patchwork of older and newer single-family homes and a large number of vacant lots. Almost half — 45% — of the lots in University Village are vacant (134 out of roughly 300).

McNeese, who serves as treasurer of the University Village Civic Club (UVCC), and other residents saw in the vacant lots an opportunity to establish a pocket park and break up one of Houston’s green-space deserts.

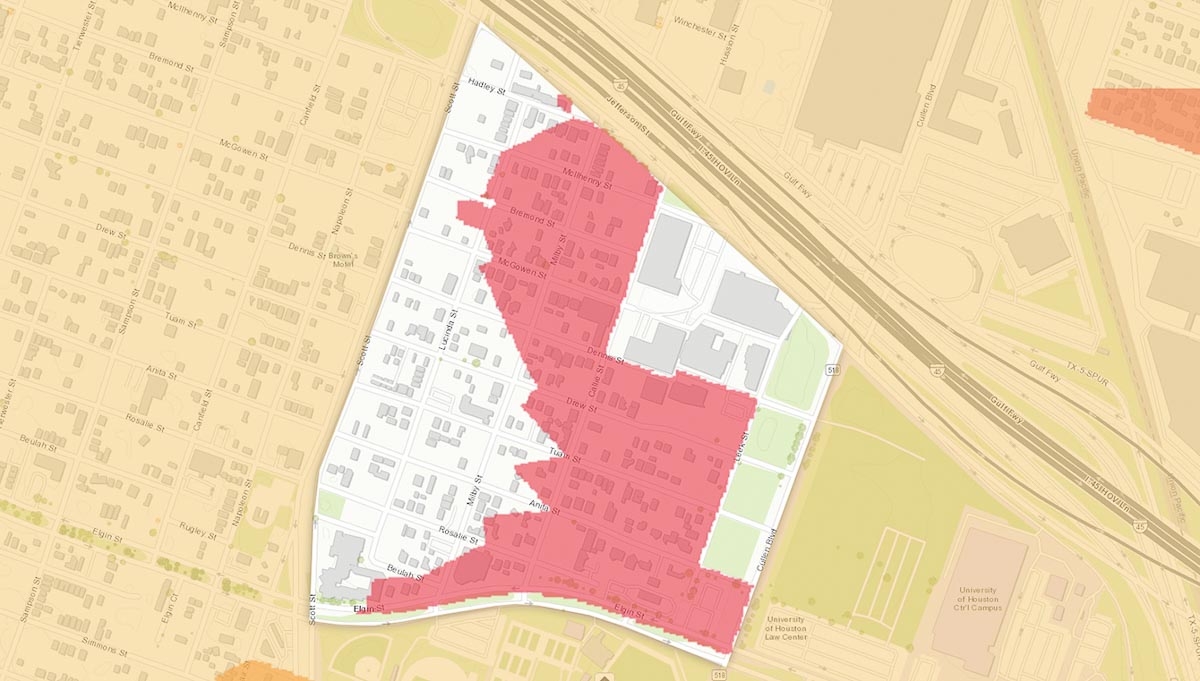

University Village is bounded by Scott Street and Cullen Boulevard to the west and east, and the Gulf Freeway and Elgin Street to the north and south. Red indicates an area with a very high need for park space.

Image source: Harris County Precinct One

What exactly is a pocket park?

When it comes to parks, bigger isn’t always better, or even necessary. In recent years, research increasingly has shown the importance and advantages of small-scale parks in providing access to quality green space close to home. The benefits range from improving health and fitness, reducing traffic and pollution and mitigating the effects of climate change, to empowering communities and making them more sociable, and building relationships between residents and city officials. Researchers have even found that crime rates go down in neighborhoods where vacant lots have been transformed into pocket parks, compared to unimproved areas.

And the lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic have provided further support, both for the need for increased park access and residents’ desire for more.

One researcher used mobile phone data to track the frequency with which people visited parks in Tokyo and how far they traveled to reach them and found significant differences in how people used larger, flagship parks versus smaller green spaces. He concluded that to optimize public health in cities, larger community and neighborhood parks (think MacGregor Park and Gragg Park Complex) need to be supplemented with even smaller, hyperlocal green spaces such as pocket parks.

Pocket parks, or mini-parks, are usually converted vacant lots and other unused or abandoned spaces. They aren’t intended to be replacements for larger neighborhood and community parks, instead, they’re meant to serve residents in the immediate area who otherwise wouldn’t have access to a play area for children or open space for small events and meeting friends. They’re meant to be specifically designed with the interests of residents in the surrounding area in mind. A couple of years ago, McNeese and his family went door to door in University Village to ask their neighbors what they would like to see in a park. Playground equipment, a splash pad and a basketball goal were among the top responses.

Successful pocket parks, according to the National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA), have four key qualities:

“They are accessible; allow people to engage in activities; are comfortable spaces and have a good image; and finally, are sociable places: one where people meet each other and take people to when they come to visit.”

Pocket parks are typically a quarter of an acre or less in size — usually no bigger than the size of a few house lots. According to the Census Bureau, the median size of a lot for new construction in 2019 was 8,963 square feet or about one-fifth of an acre. In Houston, the standard lot size is 5,000 square feet. By those parameters, a pocket park at the large end of the spectrum (a quarter of an acre or 10,890 square feet) would comprise just over two house lots — roughly 2.18 lots.

Emancipation Park is one of four existing parks in Third Ward, the others are Leroy Moses, Malone and Our Park. The pocket park in University Village will be the fifth.

Who needs a pocket park?

Third Ward was one of five pilot neighborhoods included in Mayor Sylvester Turner’s Complete Communities initiative when it was launched in 2017. The program is designed to help build up neighborhoods in need of better access to amenities and services, including grocery stores, affordable urgent-care centers and early learning and after-school programs, using funds from nonprofits, private businesses and government agencies. As part of the Complete Communities initiative, each neighborhood creates an action plan for how to address improvements determined to be top priorities by residents through a series of public meetings and workshops.

The Complete Communities action plan for Third Ward — which was approved by the City Council in 2018 — includes two goals identified by residents to deal with the paucity of parks and community amenities: improve existing area parks and expand access to public open spaces. The four existing parks in Third Ward — Emancipation, Leroy Moses, Malone and Our Park — comprise a total of 13.5 acres of park space. Emancipation accounts for 11.6 — or 86% — of those acres.

The second goal goes toward ensuring area families can access a park within a 10-minute walk and speaks to a deficit supported by the recommendations in phase II of the city’s Parks Master Plan — a 553-page playbook approved by the City Council in 2015 for improving each of Houston’s 21 park sectors, as well as the park system overall. The plan recommends at least 2.5 acres of park space per 1,000 residents. Based on the city’s recommendation, Third Ward needs an additional 21 acres of park space — University Village needs about 3 acres.

In the realm of parks and recreation, a half-mile is an important distance. It’s the farthest anyone should have to walk from where they live to reach the nearest park, according to the Trust for Public Land (TPL). That determination is based on research showing most people are willing to walk half a mile to get to a park; while most consider any farther than that to be too far on foot. This convenience threshold is crucial because once it’s crossed, people are less likely to take advantage of the physical and mental health benefits that parks provide. Many cities, Houston among them, have set the TPL standard of a half-mile — or 10-minute — walk as the goal for the maximum distance any resident should be from the nearest park. Turner is among the mayors who have committed to making sure every resident has “safe, easy access to a quality park within a 10-minute walk of home by 2050” — the same year the city has set for its Vision Zero goal.

“Quite frankly, we’re 52 percent behind the eight ball with regard to everybody having a 10-minute walk or a half-mile radius of a park within their vicinity,” Michael Isermann, deputy director of facilities management and development for Houston Parks and Recreation, told the University Village Civic Club in January when members of the University Village Civic Club met with representatives from Complete Communities, Public Works, the Parks and Recreation Department and City Council member Carolyn Evans-Shabazz’s office to discuss options for a park. “We’re only at 48 percent in the city, so it’s a problem everywhere.”

Actually, TPL’s 2020 analysis of Houston’s park system puts 61% of Houstonians within a 10-minute walk of a park. In 2016, 48% of residents lived a 10-minute walk from green space, and that share has grown in the years since, to 49% in 2018, then jumping to 58% in 2019. The average among the 100 most populous U.S. cities is 55%. By comparison, in Minneapolis, which is No. 1 in the ParkScore rankings, 98% of residents are a half-mile from a park.

The “highest need” areas for park access in Third Ward — an area that overall is 21 acres of green space short of where it needs to be — are the southeast sector and “in the University Village neighborhood on the northeast side,” according to its Complete Communities action plan. That’s based on data from the Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore Project.

Not only does University Village have one of the greatest needs for parks improvement in Third Ward, it also has one of the greatest needs in all of Harris County Precinct One, according to the Park-Smart Precinct One Plan — an effort to build community resilience and improve equitable access to green space through the expansion of parks and trails. Working with the Trust for Public Land, maps were created to show available green space, location and severity of heat islands, socioeconomic vulnerability, air and water quality, and flood risk in Precinct One. A decision support tool was also created to pinpoint areas that should be prioritized for park improvements.

Ed Pettitt used the tool to help inform decisions about where best to focus efforts to offset Third Ward’s park-space deficit when he led the working group that addressed issues related to parks and neighborhood character for Third Ward’s Complete Communities strategy. He analyzed data on green space and health and socioeconomic disparities in Greater Third Ward and found the University Village neighborhood had — by far — the greatest need for a park.

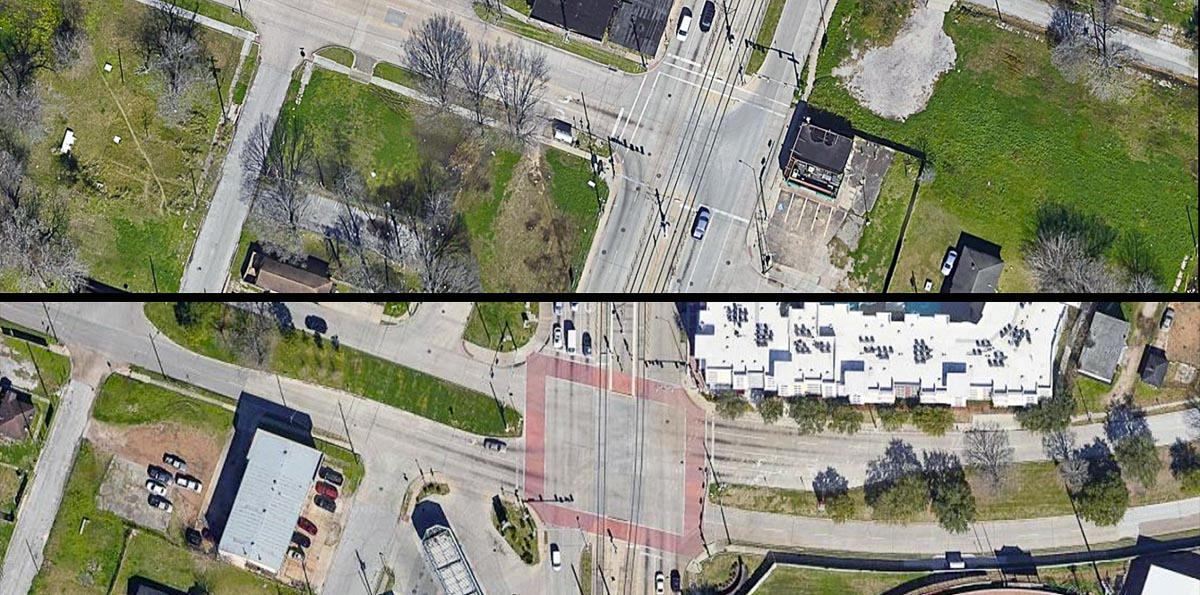

Zurrie M. Malone Park — a 0.69-acre pocket park — is the closest park to University Village. “As the crow flies,” which is how the Houston Parks and Recreation Department measures distance when determining green space deficiencies and park needs, Malone Park is 0.4 miles from the neighborhood. Unlike crows, however, people don’t fly, and to reach Malone Park, residents of University Village have to either walk 0.8 miles south to the intersection of Scott and Elgin or 0.7 miles north to the intersection of Scott and McGowen. That’s because fence safety barriers on the Purple Line of the light rail, which runs along Scott, prevent crossing at six of the 10 streets that cut northwest/southeast through the neighborhood. The closest crossings are at Scott and McGowen or Elgin. It’s doubtful any parent would allow their child to go to the park if it required crossing either of those intersections.

To cross Scott Street, residents of University Village have to go to either the intersections of Scott and McGowen or Scott and Elgin.

Images from Google Maps

“There are barriers that you don’t always see from the sky,” Isermann said. In this case, the unseen barrier is Scott Street. “We only use the ‘crow flies’ thing to measure our distances; we don’t see all of the barriers, other than major freeways.”

The Trust for Public Land, on the other hand, calculates a city’s share of residents within a half-mile of a park using routes without physical barriers such as highways, train tracks and rivers without bridges.

How to get a pocket park

To help close the Third Ward’s gap in green space, community members decided on a plan to identify potential properties, such as vacant lots and land owned by nonprofits, that could be acquired and developed into pocket parks or plazas — particularly in the eastern portion of the neighborhood.

With high hopes and a city-approved action plan in hand, residents set out to create a pocket park in University Village.

Marvin McNeese and Brian Van Tubergen, the president of the University Village Civic Club, worked with Pettitt to find a location for a park and ways to partner with the parks department and other organizations to help with the design and funding.

Pettitt is no stranger to taking an iterative and dogged approach to meeting neighborhood needs. When a vacant lot that served as the home of the Third Ward Chess Club was sold to a developer, he found a local real estate developer who was willing to let the club use a piece of property at McGowen and Live Oak that volunteers transformed into the Third Ward Chess Park.

Van Tubergen, who has lived in University Village since the mid-2000s, had in mind a specific vacant lot in the neighborhood, one that he saw as a solution to two existing needs: green space and cleaning up an unsightly and neglected piece of property. For years, Van Tubergen has waged a campaign to stop illegal dumping on the lot, going so far as to install a fake camera on a telephone pole 10 years ago as an “experiment to see how I could keep people from dumping.” His fake camera experiment worked for a month or two, but eventually, he says, his ruse was puzzled out, and “then they’d just start dumping again.”

Public Works owned the lot, so Van Tubergen and the other residents decided to approach the city with their plan to make the property a park. It seemed like a simple solution, but remember, they say nothing worthwhile is ever easy. Identifying a location for a pocket park is just the first — and possibly easiest — step in the process. After that, comes the more difficult task of finding the funding to acquire the property and build the park.

The University Village Civic Club is planning to turn this vacant lot at Lucinda and Anita into a pocket park for the neighborhood.

Photo courtesy of University Village Civic Club

How to fund a pocket park

Although the lot technically belongs to the city, to make it a park, ownership would have to be transferred from Public Works to the Parks and Recreation Department. That can’t be done without money moving from one department to the other. And, even if that could happen, it doesn’t mean the parks department would simply green-light the project and add the “University Village Pocket Park” to its inventory, because after acquisition, there’s still the cost of development and the ongoing maintenance of a park. Houston, like other cities, faces a large budget deficit because of revenue losses related to the COVID-19 pandemic. (Not to mention the City of Houston’s fiscal struggles existed even before COVID-19.) And when city budgets get cut, park services typically are first on the chopping block. (Mayor Turner’s proposed 2020-2021 budget suggested slashing parks funding by more than 10%.)

Last May, the Kinder Institute released a report comparing the revenue structure and service levels for Houston, San Antonio and Dallas, which showed Houston devotes less general fund money to parks than other, small cities such as Dallas ($90 million versus $78 million in fiscal year 2019–2020). And more than any other city in the nation besides New York and San Francisco, Houston depends on private contributions to plug the gap in its parks revenue. However, much of this revenue is devoted to capital improvements, not operations such as park maintenance, and because many park conservancies are devoted to a single park, the private funds are not equitably distributed across the city’s park system.

Options for financing parks include funding from Tax Increment Reinvestment Zones, management districts and private donations managed by the Houston Parks Board. University Village isn’t located in a TIRZ, but it is part of the Greater Southeast Management District.

Residents in the Near Northside worked with the Greater Northside Management District (GNMD) and Avenue CDC, a community development nonprofit, to convert a pair of overgrown vacant lots on Fulton Street owned by the Parks Department into a Butterfly Pocket Park. It didn’t happen overnight, but after five years, the park was completed last year. Funding for the park came in part through a “Visit My Neighborhood” grant from the Houston Arts Alliance that Avenue CDC helped secure.

There’s also the city’s Park and Open Space funds, which are collected from developers that pay $700 to the parks department for each newly built housing unit. The funds primarily are used for purchasing plots of land, capital improvements and maintenance. However, the amount of money available in the Park and Open Space fund for each park sector is dependent on development in that sector; and funds for renovating an existing park or building a new one have to be generated in the park sector where the park is located.

In other neighborhoods, such as Midtown and Montrose in Park Sector 14, there’s a lot of high-end, dense development that generates more funding for parks. In comparison, University Village is located in Park Sector 15, which doesn’t generate as much money for parks funding because there isn’t as much new development.

Many argue the current park sector financing scheme, which dates back to the 1980s, is outmoded and doesn’t address the ongoing needs of the Complete Communities. Indeed, it doesn’t seem to support the initiative’s targeted goal of strengthening struggling neighborhoods and ensuring Houston isn’t “two cities in one, a city of haves and have-nots,” as Turner stated when he unveiled details of the program in 2017.

“The more development that has occurred in a neighborhood, the more money it has for new parks,” Third Ward’s Pettitt says. “That’s why HPARD is building lots of dog parks around Midtown and Upper Kirby, but says it’s broke when residents on the east side ask for a park. Only new residents (and their dogs) get new parks.”

To sidestep the outdated financing scheme and fund projects in Complete Communities neighborhoods, the city launched the 50/50 Parks Partner Program in 2019. The 50/50 Park Partners initiative is an effort to improve 50 neighborhood parks with help from 50 private businesses in the form of funding, volunteers and in-kind support. The public-private partnership is led by the Houston Parks Board, Houston Parks and Recreation Department, and Greater Houston Partnership, and was established to promote park equity, community engagement and long-term sustainable impact.

Working through options in University Village

Back in mid-January, when members of the University Village Civic Club met with city representatives to discuss options for a park, one idea discussed was an arrangement in which Public Works would convert the vacant lot it owned into a pocket park that the civic club would take responsibility for maintaining. Initially, the agreement seemed to solve the problem; however, in that scenario, the civic club would be required to carry insurance on the pocket park and would be liable if anyone using it was hurt. For a small civic club, Van Tubergen says, that just isn’t financially tenable.

Another possibility discussed was the city selling the property to the civic club, which would then convert it into a park. But, going the route of a private option again proved to be a nonstarter for the residents because of the cost of indemnity protection.

“It’s hard enough to get officers just to volunteer to be on board with a civic club,” Van Tubergen explains, “let alone exposing our assets to unlimited liability if a child should — God forbid — break their neck on a playground.

Van Tubergen gives the city credit for its effort, and says the departments “really have been trying” to help facilitate a park in University Village. And he understands what he sees as the parks department’s reluctance to add “hundreds of small, little parks” to its inventory, even if civic clubs such as his commit to handling park maintenance (for example, if the club disbands for some reason, then that responsibility would be left to the city). But that doesn’t mean he won’t stop pushing for parks equity in Houston.

Shannon Buggs, the director of Complete Communities, confirmed at least four Complete Communities have made requests to turn city-owned vacant land into pocket parks. “We have been working to see if there is a way of establishing a policy and a procedure for addressing these concerns and requests when they come up,” Buggs said. “We haven’t gotten there yet. We’re still exploring what it all takes, but it’s been complicated.”

Thinking bigger than a pocket park

By the end of the meeting, the discussion turned from creating a 5,000-square-foot pocket park on a single city lot to the possibility of a park four to six times larger.

“I think that one of the things that counted as troubling for us is that about an eighth of an acre isn’t really much of a park,” Isermann of the parks department said. “If there’s an opportunity to take a look at a larger purchase, that would make sense with regard to giving you all the kind of room you need to do some of these things (you want to do with the park).”

That would mean room for a playground and a splash pad, and maybe even the basketball goal that residents said they wanted. Van Tubergen says he’s spoken to the developer who owns the properties adjacent to the two owned by Public Works, and the owner is willing to sell the lots to the city for a park. The next step would be getting appraisals on the land, then, once he has a dollar amount and city approval, Marvin McNeese, who, in addition to being a professor of political science at the College of Biblical Studies–Houston, is a grant writer, can begin writing funding proposals.

For now, the residents of University Village will continue to wait for word from the city. McNeese, who began advocating for a neighborhood park more than four years ago, is willing to wait a little longer. He just hopes it happens while his four kids are still young enough to enjoy the benefits. But if not, he’ll be happy knowing other kids coming up in the neighborhood won’t have to play in the street.

Update: On Tuesday, April 20, the University Village Civic Club learned that Houston Public Works and the Houston Parks and Recreation Department (HPARD) reached an agreement to transfer a vacant lot that has been targeted by the civic club for use as a pocket park over to the parks department. Kenneth Allen, HPARD’s interim director, signed the agreement on Monday, bringing the 5,000-square-foot property into the HPARD portfolio. The deal means the lot can be used as a public park.

This story was completed just before the agreement on the lot transfer was announced.