This post is part of a series highlighting the findings from the 2022 Kinder Houston Area Survey. View the full report here.

It’s the stupid economy

In the two years since the pandemic’s opening salvo, Harris County alone has recorded 1 million cases and over 10,000 deaths. The nation recently marked the solemn occasion of its 1 millionth death. Despite this heavy toll, in a number of ways, the initial shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has faded: Periodic waves new variants and infections, news of new booster shots, and waning public health mandates have marked our new status quo.

The new crisis? Pick your headline: record gas prices, retail and raw material shortages, double-digit percentage price increases for everyday groceries, car dealership markups, unreal real estate, recession fears, and the like. In other words: It’s the stupid economy. (Not to be confused with the Bill Clinton-era slogan, “It’s the economy, stupid.”)

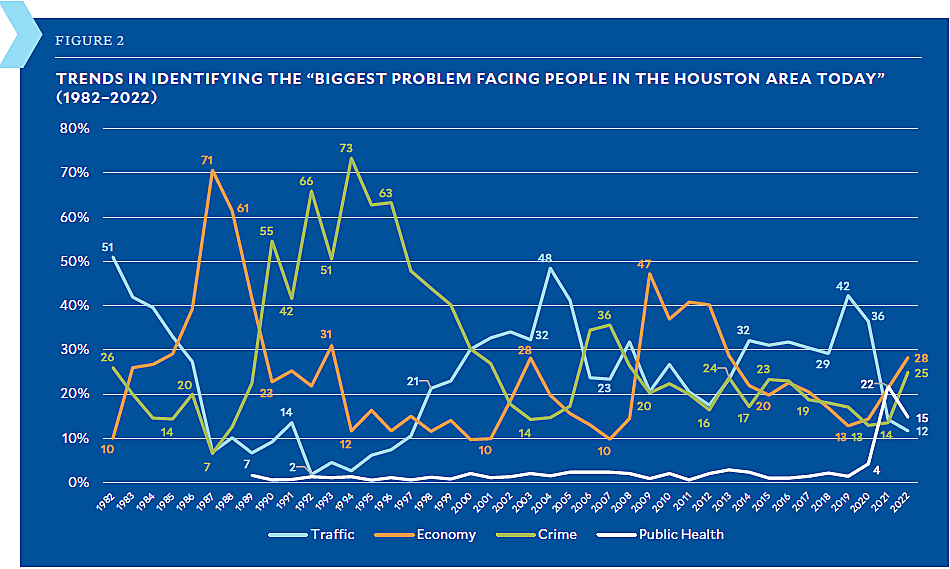

In particular, the cost of living—including housing and gasoline costs—was most frequently cited by respondents in the Kinder Houston Area Survey as the biggest problem facing people in the city. Some 28% of Houstonians named it the biggest problem, but perhaps many more would consider it a big problem in general; after all, 70% of Americans rated inflation as a “very big problem” in a recent Pew survey. (Different survey, different methodology—Pew asks respondents to rate the severity of a list of several problems. The Kinder survey asks respondents to name the biggest problem that comes to mind.)

Inflation is neither simply local nor national in scope: It is hitting nearly every advanced economy around the globe, with price indices up 6% on average. Our experience in the US is not as bad as it was in the early 1980s, when the Houston Area Survey debuted and when inflation was coming off of highs of 13%. Gas prices, even now at “historic highs,” technically aren’t as bad as they were then when inflation is factored in. And when you consider fuel efficiency gains over the last 40 years, we’re still getting a deal on gas: It costs about $16.65 to drive 100 miles today compared to almost $25 then, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis.

While housing prices are also up just about everywhere, this is one economic indicator that is more local in scope. In the Houston area, a new affordability index by the Houston Association of Realtors found median sales prices have risen $80,000 in the past year. At that level, homebuyers would need to earn almost 27% more income this year than they did last year to afford the median-priced home on the market.

This tracks with a trend the Kinder Insitute has been exploring in its State of Housing reports, which demonstrate that homeownership slips further out of reach of the county’s renter population every year. Meanwhile, rents in Houston have risen 23% in the past seven years, eroding the ability to build up the savings needed to make a down payment.

Local governments can do little to mitigate this in the short term, but they can and should prepare for the fallout: Evictions and homelessness become more prevalent when housing prices rise. We are already seeing early indications of this: Eviction filings in Houston were up 80% over the average level in March and have remained above average in April and May, according to data from the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

Dim prospects, dangerous disparities

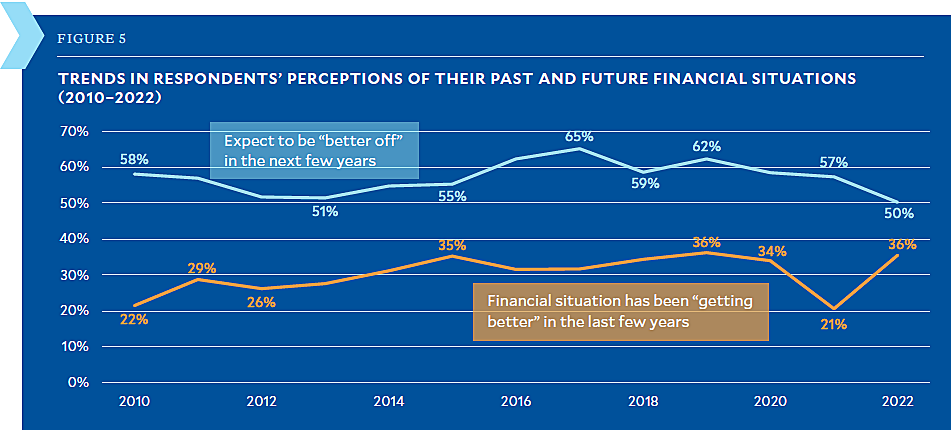

These concerns are rising even as more people reported being in better financial shape in recent years—36% said so this year compared to 21% in last year’s survey.

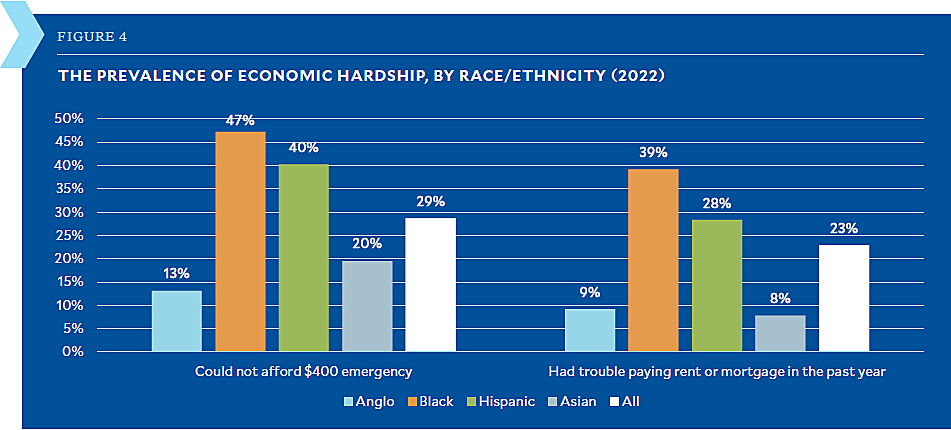

One benchmark of financial resiliency is measured by asking respondents whether they could come up with the cash to cover a $400 emergency. In 2019, almost 40% said they could not; this year, 29% said so—suggesting more people are indeed better off than they used to be. As inflation takes a toll, however, this number could creep back up.

Meanwhile, only 50% of respondents—the lowest level recorded and a drop from 65% in 2017—say they think they’ll be better off in the next few years.

Clearly, this stems from the aforementioned economic concerns, mixed with uncertainty about what the “postpandemic” world will look like in the coming years.

“We’re an optimistic city. It’s hard not to be optimistic in Houston. What we are seeing this year is a reflection of a coming together of forces” that are feeding a general sense of unease, Stephen Klineberg said during his remarks at the Kinder Institute Luncheon, where this year's survey results were unveiled.

In this year’s survey, Houstonians demonstrated a strong shift in perception about how race can limit opportunities—a marker of increased awareness about the pernicious effects of racism in this country. Across every major ethnic category, fewer Houstonians this year said they agreed with the statement: “Blacks and minorities have the same opportunities as whites in the U.S. today.” The drop was sharpest among whites themselves: In 2019, 64% agreed that opportunities were equitable; this year, only 49% think so.

This reflects a more realistic view of conditions that have become well documented but difficult to correct, ranging from the racial bias in home appraisals and home loans to the disparities in local disaster recovery. This growing awareness builds on last year’s finding that more Houstonians agree that the criminal justice system is biased against Black people.

Even this year’s Houston Area Survey finds evidence of disparity, as 23% of Houston residents reported being unable to pay their rent or mortgage in the past year. The proportion was higher for Blacks (39%) and Hispanics (28%). Likewise, the share of people who could not cover a $400 emergency was starkly higher among these groups than for whites and Asians.

As survey founder Stephen Klineberg often asserts, these racial disparities pose huge risks to Houston’s long-term prosperity, given the widespread demographic changes the city has experienced and is continuing to experience. If we do not figure out how to expand opportunities and build on-ramps to stable, healthy, and happy lives for all people, the city should never expect to be better off than it is today.